Can Law Breakers Be Law Makers?

*Nilesh Ekka/Akanksha Baldawa

“All institutions are prone to corruption and to the vices of their members”~ Morris West

In a democracy, the elected representatives are responsible for governing the country; therefore, it is of utmost importance, that the people who enter the field of politics have a clean image and high moral character. However, the current trends reflect otherwise. Today, by far the most reiterated statistic with regard to the India political scenario is that more than one third Parliamentarians have criminal charges against them with some facing serious charges like murder, attempt to murder, kidnapping etc.

Crime and Politics

The election of criminal elements to the Parliament as well as State Legislative Assemblies and Councils is among the most pressing problems that plague Indian politics today. While criminals are found in almost every profession, it is ironical that individuals facing charges of heinous crimes are able to contest elections, represent the citizens of this country and function as lawmakers of the land, without any major deterrents. Simply put, those who break the law should not make the law.

Despite the best intentions of the drafters of the Constitution and the Members of Parliament at the onset of the Indian Republic, the fear of a nexus between crime and politics was widely expressed from the first general election in 1952. Interestingly, the nature of this nexus changed in the 1970s. Instead of politicians having suspected links with criminal networks, persons with extensive criminal backgrounds began entering politics. This was confirmed in the Vohra Committee Report in 1993, and again in 2002 in the report of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC). The Vohra Committee report pointed to the rapid growth of criminal networks that had in turn developed an elaborate system of contact with bureaucrats, politicians and media persons. A Consultation Paper published by the NCRWC in 2002 went on to say that criminals were now seeking direct access to power by becoming legislators and ministers themselves.

Since the 2002 and subsequently in 2003 judgment of the Supreme Court in Union of India v. Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), (which made the analysis of criminal records of candidates possible by requiring such records to be disclosed by way of affidavit), the public has had a chance to make informed decisions in elections. The result of such analysis also leads to considerable concern.

For instance, between 2003 and 2013 i.e. ten years since criminal, financial and other background details of candidates contesting elections were made public, 18% of candidates contesting either National or State elections have criminal cases pending against them (11,063 out of 62,847). In 5,253 or almost half of these cases (8.4% of the total candidates analyzed), the charges are of serious criminal offences that include murder, attempt to murder, rape, crimes against women, cases under the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, or under the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act, 1999 which on conviction would result in five years or more of jail, etc. As many as 152 candidates had 10 or more serious cases pending, 14 candidates had 40 or more such cases and 5 candidates had 50 or more cases against them.

The 5,253 candidates with serious cases together had 13,984 serious charges against them. Of these charges, 31% were cases of murder and other murder related offences, 4% were cases of rape and offences against women, 7% related to kidnapping and abduction, 7% related to robbery and dacoity, 14% related to forgery and counterfeiting including of government seals and 5% related to breaking the law during elections.

Criminal backgrounds are not limited to contesting candidates, but are found among winners as well. Of these 5,253 candidates with serious criminal charges against them, 1,187 went on to winning the elections they contested i.e. 13.5% of the 8,882 winners analyzed from 2004 to 2013. Overall, including both serious and non-serious charges, 2,497 (28.4% of the winners) had 9,993 pending criminal cases against them.

The average assets of all candidates analyzed between 2004 and 2013 was Rs. 1.37 crores. The average assets of all MPs/MLAs analyzed was Rs. 3.83 crores. MPs and MLAs charged with serious crimes had higher average assets, Rs. 4.30 crores and Rs. 4.38 crores respectively.

|

No. of Candidates Analyzed (2004-2013) |

No. of MPs/MLAs Analyzed (2004-2013) | No. of MPs/MLAs with criminal cases (2004-2013) | No. of MPs/MLAs with Serious Charges (2004-2013) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 62847 | 8790 | 2575 | 1187 |

| Average Assets | Rs. 1.37 Crores | Rs. 3.83 Crores | Rs. 4.30 Crores | Rs. 4.38 Crores |

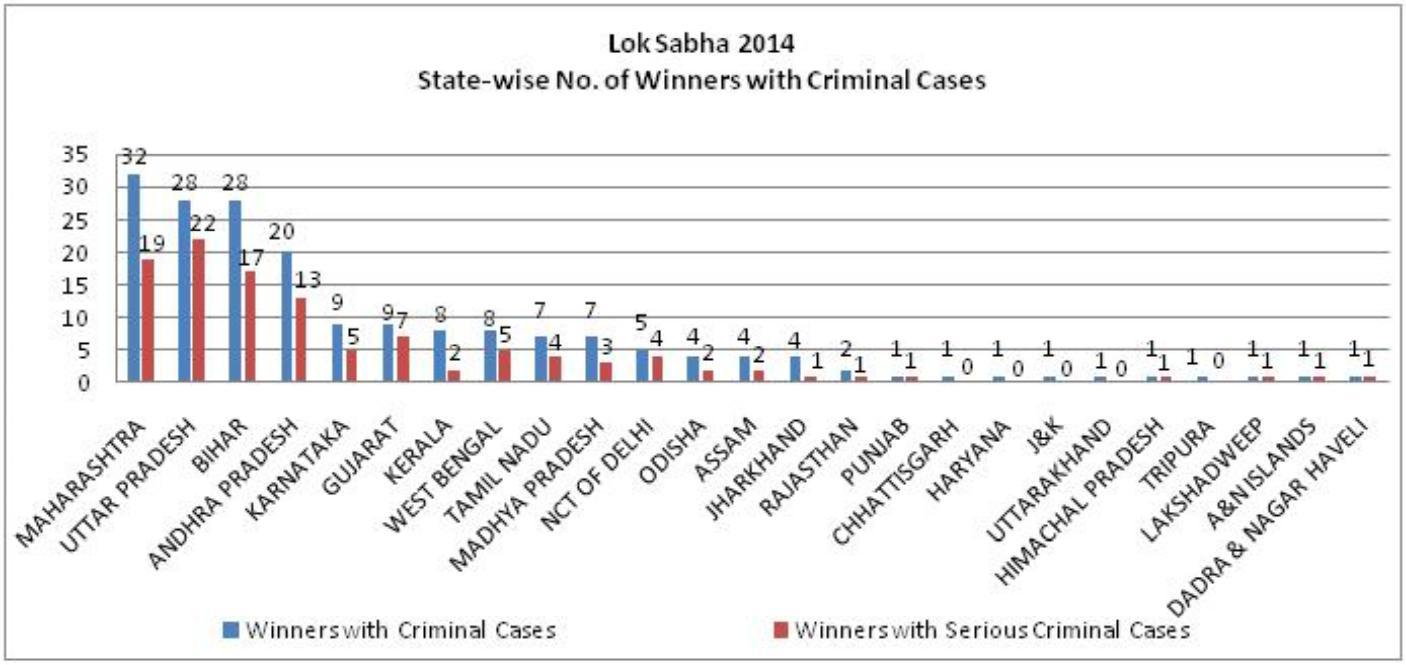

In the current Lok Sabha, 34% or 183 out of the 542 Lok Sabha MPs analyzed have declared criminal cases. 116 MPs have declared cases with serious charges like murder, attempt to murder, kidnapping etc. Further, the prevalence of MPs with criminal cases pending has only increased over time. In 2004, 24% of Lok Sabha MPs had criminal cases pending, which increased to 30% in the 2009 elections and now 34% in the 2014 elections.

| Name | 2014 Lok Sabha Elections | 2009 Lok Sabha Elections | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of winners analyzed | Winners width declared Criminal class | % of winners with declaredn Criminal Cases | winners with serious declared criminal cases | % of winners with serious declared criminal cases | Total number of winners analyzed | Winners width declared Criminal class | % of winners with declaredn Criminal Cases | winners with serious declared criminal cases | % of winners with serious declared criminal cases | |

| BJP | ||||||||||

| INC | ||||||||||

| AIADMK | ||||||||||

| AITC | ||||||||||

| BJD | ||||||||||

|

SHIV SENA |

||||||||||

| TDP | ||||||||||

| TRS | ||||||||||

| CPI(M) | ||||||||||

| YSRCP | ||||||||||

| LJP | ||||||||||

| NCP | ||||||||||

| RJD | ||||||||||

| JKPDP | ||||||||||

| JD(U) | ||||||||||

| IND | ||||||||||

| Others | ||||||||||

| Total | ||||||||||

Comparison of Lok Sabha 2014 and 2009: Criminal Cases

| State |

Total number of Winners analyzed |

Winners with declared criminal cases |

% of Winners with declared criminal cases |

Winners with serious declared criminal cases |

% of Winners with serious declared criminal cases |

| Uttar Pradesh | 80 | 28 | 35% | 22 | 28% |

| Maharashtra | 48 | 32 | 67% | 19 | 40% |

| Bihar | 40 | 28 | 70% | 17 | 43% |

| Andhra Pradesh | 42 | 20 | 48% | 13 | 31% |

| Gujarat | 26 | 9 | 35% | 7 | 27% |

| Karnataka | 28 | 9 | 32% | 5 | 18% |

| West Bengal | 42 | 8 | 19% | 5 | 12% |

| National Capital Territory of Delhi | 7 | 5 | 71% | 5 | 12% |

| Tamil Nad | 39 | 7 | 18% | 4 | 10% |

| Madhya Pradesh | 29 | 7 | 24% | 3 | 10% |

| Orissa | 21 | 4 | 19% | 2 | 10% |

| Kerala | 20 | 8 | 40% | 2 | 10% |

| Assam | 14 | 4 | 29% | 2 | 14% |

| Jharkhand | 13 | 4 | 31% | 1 | 8% |

| Punjab | 13 | 1 | 8% | 1 | 8% |

| Rajasthan | 25 | 2 | 8% | 1 | 4% |

| Himachal Pradesh | 4 | 1 | 25% | 1 | 25% |

| Lakshadweep | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% |

| Andaman & Nicobar Islands | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% |

| Dadra & Nagar Haveli | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 100% |

| Chhattisgarh | 11 | 1 | 9% | 0 | 0% |

| Haryana | 10 | 1 | 10% | 0 | 0% |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 6 | 1 | 17% | 0 | 0% |

| Uttarakhand | 5 | 1 | 20% | 0 | 0% |

| Tripura | 2 | 1 | 50% | 0 | 0% |

| Others | 14 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 542 | 185 | 34% | 112 | 21% |

State-wise Comparison of Lok Sabha 2014 and 2009: Criminal Cases

State-wise Criminal Cases: Lok Sabha 2014

The situation is similar across states with 34% or 1,392 out of 4,072 sitting MLAs with pending cases, with about half being serious cases. Some states have a much higher percentage of MLAs with criminal records: in Jharkhand, 65% of MLAs have criminal cases pending. A number of MPs and MLAs have been accused of multiple counts of criminal charges. In a constituency of Uttar Pradesh, for example, the MLA has 36 criminal cases pending against him including 14 cases related to murder.

|

State |

Total number |

No. of |

% of |

No of Criminals |

% of criminals |

|

|

of Winners |

Criminals |

Criminals |

with Serious |

Crime with |

|

|

Analyzed |

|

|

|

Serious Crime |

|

Jharkhand |

81 |

53 |

65.43% |

41 |

50.62% |

|

Kerala |

140 |

87 |

62.14% |

26 |

18.57% |

|

Bihar |

243 |

141 |

58.02% |

97 |

39.92% |

|

Maharashtra |

283 |

160 |

56.54% |

111 |

39.22% |

|

Telangana |

119 |

67 |

56.30% |

47 |

39.50% |

|

Andhra Pradesh |

174 |

84 |

48.28% |

39 |

22.41% |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

399 |

181 |

45.36% |

84 |

21.05% |

|

Puducherry |

30 |

11 |

36.67% |

4 |

13.33% |

|

West Bengal |

293 |

107 |

36.52% |

93 |

31.74% |

|

Odisha |

147 |

52 |

35.37% |

41 |

27.89% |

|

Delhi |

70 |

24 |

34.29% |

14 |

20.00% |

|

Karnataka |

215 |

73 |

33.95% |

38 |

17.67% |

|

Tamil Nadu |

223 |

74 |

33.18% |

41 |

18.39% |

|

Gujarat |

174 |

54 |

31.03% |

24 |

13.79% |

|

Goa |

40 |

12 |

30.00% |

3 |

7.50% |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

230 |

70 |

30.43% |

45 |

19.57% |

|

Uttarakhand |

66 |

16 |

24.24% |

5 |

7.58% |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

67 |

14 |

20.90% |

5 |

7.46% |

|

Rajasthan |

200 |

37 |

18.50% |

20 |

10.00% |

|

Chhattisgarh |

90 |

15 |

16.67% |

8 |

8.89% |

|

Punjab |

117 |

17 |

14.53% |

7 |

5.98% |

|

Assam |

126 |

14 |

11.11% |

10 |

7.94% |

|

Haryana |

90 |

9 |

10.00% |

5 |

5.56% |

|

Tripura |

60 |

6 |

10.00% |

5 |

8.33% |

|

Arunachal Pradesh |

60 |

5 |

8.33% |

5 |

8.33% |

|

Sikkim |

32 |

2 |

6.25% |

1 |

3.13% |

|

Jammu & Kashmir |

87 |

5 |

5.75% |

2 |

2.30% |

|

Meghalaya |

60 |

1 |

1.67% |

0 |

0.00% |

|

Nagaland |

60 |

1 |

1.67% |

0 |

0.00% |

|

Manipur |

56 |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

|

Mizoram |

40 |

0 |

0.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

|

Total |

4072 |

1392 |

34.18% |

821 |

20.16% |

State-wise MLAs with Criminal Cases

From this data it is clear that about one-third of elected candidates at the Parliament and State Assembly levels in India have some form of criminal taint. Data also suggests that one-fifth of MLAs have pending cases with charges being framed against them at the time of their election. Even more disturbing is the finding that the percentage of winners with criminal cases pending is higher than the percentage of candidates without such backgrounds. The increasing percentage of candidates being fielded by political parties in successive Lok Sabha Elections had led to a number of studies that seek to analyze the reason for the same. One such study titled “The Market for Criminality: Money, Muscle And Elections in India” by Milan Vaishnav indicates that parties favor criminal candidates as they have access to wealth which in turn allows them to finance elections independently. His paper has found ‘money’ and ‘muscle’ complementing each other in the case of the Indian electoral scene. Data also showed how a larger percentage of candidates (23%) with criminal cases went on to win elections as opposed to candidates with a clean record (13%). All of this has set in place a vicious cycle of sorts, where parties in a bid to increase the ‘winnability’ quotient of their candidates give tickets to individuals with a tainted record. Not only do political parties select candidates with criminal backgrounds, there is evidence to suggest that untainted representatives later become involved in criminal activities.

Another factor for political parties declaring candidates with criminal records is the lack of inner party democracy. There is hardly any candidate selection procedure in most political parties and decisions are taken by the elite leadership of the party.

Thus, the crime-politics nexus demands a range of solutions much broader than disqualification or any other sanctions on elected representatives. It requires careful legal insight into the functioning of the political parties and regulating the internal affairs of parties. Political parties form the Government and hence govern the country. It is therefore, necessary for political parties to have internal democracy, financial transparency and accountability in their working. A political party which does not respect democratic principles in its internal working cannot be expected to respect those principles in the governance of the country. It cannot be dictatorship internally and democratic in its functioning outside.

The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) highlighted similar concerns on the functioning of political parties and recommended a separate law for regulating some of the internal affairs of political parties in order to deal with the crime-politics nexus.

Though the Representation of the People Act (RPA) disqualifies a sitting legislator or a candidate on certain grounds, there is virtually no regulation for the appointments to offices within the organization of the party. Political parties play a central role in Indian democracy. Therefore, a politician may be disqualified from being a legislator, but may continue to hold high positions within his party. Convicted politicians may continue to influence law-making by controlling the party and fielding proxy candidates in legislature. In a democracy essentially based on parties being controlled by a high-command, the process of breaking crime-politics nexus extends much beyond the legislators and encompasses political parties as well.

Lack of Financial Accountability in Politics

The increasing criminalization of politics is coupled with the lack of financial accountability. Of the 3,452 candidates who contested more than one election (including all state assembly elections and the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha elections) from 2004 to 2013 as many as 2,967 showed an increase in wealth. The average declared wealth of such re-contesting candidates in 2004 was Rs 1.74 crore, and Rs 4.08 crore in 2013, an increase of 134%. For winners, the average assets went up from Rs 1.8 crore to Rs 5.81 crore, an increase of 222%. The winners were able to increase their wealth much faster than other candidates.

The 2014 Lok Sabha elections also witnessed a very capital intensive campaign by most of the political parties. According to a study by the Centre for Media Studies, a whopping Rs. 30,000 crores was projected to be spent by the government, political parties and candidates in the 2014 general election, making it the most expensive election in Indian history. Of the estimated Rs. 30,000 crores, official spending by the Election Commission of India (ECI) and the Government of India was around Rs. 7,000 – Rs. 8,000 crores.

Most of the election campaigns were centred on the issues of black money abroad and corruption in India. The political discourse, however, did not address the issues regarding black money generated in India, especially during elections and in the functioning of political parties. The ECI reported that during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, around Rs.300 crores of unaccounted cash and more than 17,000 kg of drugs and huge amount of liquor, arms etc. were seized. This, some claim, is a conservative estimate of the actual amount of illegal and illicit funds moblized during the elections.The estimation of black money in electoral politics is fraught with methodological difficulties and hence cannot be computed, however, ADR has scrutinized the affidavits submitted by the candidates contesting elections and the financial accounts of political parties submitted to the ECI and the Income Tax (IT) Department indicating the pervasiveness of this issue. Black money, while difficult to trace, can be determined from what remains undisclosed in the financial accounts of the candidate and political parties and the discrepancies found in these submissions.

Election Expenditure by Candidates and Political Parties

Election expenditure and the substantial influx of black money in electoral polls have been a topic of concern over the past few elections. A former Chief Election Commissioner said that the 2012 Uttar Pradesh Assembly Election was marked by the expenditure of over Rs 10,000 crore of black money. If this were to be the case throughout Assembly seats in India, the amount would add up to around Rs 100,000 crores. Over the years, the limits imposed on the expenditure of candidates has been hotly contested by the political community on the grounds that the limits were too low and unrealistic. Despite these claims by the candidates, the expenditure declared by them has been consistently well below the cap on the expenditure imposed.

The candidates and political parties are required to submit their expenditure statements to the ECI after the poll results are announced. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the average election expenditure declared by the candidates was only Rs. 40.30 lakhs i.e. 59% of the limit imposed. A total of 108 (20%) MPs declared that they had incurred no expenses on campaigning through electronic/print media. The underreporting of expenses by candidates during elections warrants scrutiny of their expenditure statements.

Further, candidates usually do not disclose the sources of funds from individuals, corporations or others. This information is crucial in view of full disclosure and as of now there is no strict penalty on the nondisclosure of such information in the election expenditure statements.

In case of election expenditure disclosed by political parties, even after several notices by the ECI, the statements are submitted woefully late. Investigation into these statements are crucial in the period right after the elections. The more delayed the submission by the political parties are, the more difficult it becomes to question its veracity. Upon comparing the election expenditure statements submitted by political parties and candidates for the Lok Sabha elections in 2009, it was found that while national parties declared giving 138 MPs more than Rs. 14.19 crores, only 75 MPs declared having received any amount from their parties. These MPs declared in their statements only a total of Rs. 7.46 crores received from the political parties.

The elections conducted in the recent past have witnessed a massive investment of money from various industry giants, big corporations, as well as individual donors. Out of the funds collected during Lok Sabha elections, 2014, the national political parties declared in their election expenditure statements that Rs 408.75 crores (35.28% of total funds collected) was by cash. As the parties are not required to provide details of the donors who donated specifically during election period, these donations in cash will remain unknown.

Growth of Assets and Disclosure by Candidates

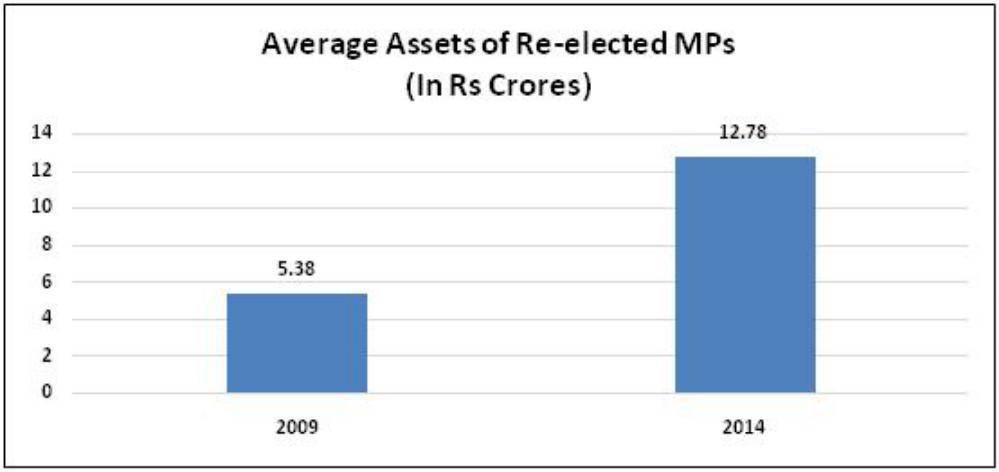

Extraordinary growth can be observed in the assets of re-elected MPs in the Lok Sabha 2014 elections. Out of 165 re-elected MPs 32 had shown an increase in total assets worth more than Rs.10 crores in five years. Data from citizen watch exercises conducted by ADR during the 2014 Lok Sabha Elections reveals that the assets of 165 MPs who were re-elected to the 2014 Lok Sabha increased by a whopping 137% since 2009. While the mandatory affidavits filed by candidates prior to elections requires them to declare their financials, there is both the lack of a process that allows for the careful scrutiny of these affidavits as well unavailability of the desired resources within the ECI to achieve the same.

Comparison of average assets of re-elected MPs (2009 vs 2014)

There are no provisions for the scrutiny of affidavits or the election expenditure of candidates. While efforts have been made by the ECI to involve the IT department in the scrutiny of affidavits of candidates and MPs who show a high growth in assets, there has been little progress in this regard. As per media reports, many candidates pay exorbitant amounts of money to get tickets from political parties. This expenditure is neither accounted for in the expenditure statements of the candidates, nor in the financial accounts of their political parties.

Further, candidates often disclose the cost price of their immovable assets, like agricultural land, commercial and residential buildings etc instead of their market value. There is no provision in the affidavits of the candidates to disclose their sources of income. The lack of any kind of scrutiny in discrepancies such as these in the financial accounts of political parties and the candidates give way to the amassing and transfer of wealth that remains undisclosed to public authorities.

Political Party Finances and Disclosure

The past decade has seen a growing stranglehold of money over elections. The analysis of IT Returns of National Parties between FY 2004-05 and 2011-12 shows that the total income of the parties from unknown sources of income amounted to Rs.3,677.97 crores (75.1% of total income of national parties) . The non-disclosure of sources of income of political parties for donations that amount to more than Rs. 20,000 leads to a wide gap in the transparency of funds.

While the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) declared a total income of Rs.585.07 crores between FY 2004-05 and 2012-13 of which Rs.307.31 crores were from voluntary contributions, the names and other particulars of these 'voluntary' contributors are not known. While the party has maintained that no donations above Rs.20,000 was received thereby not declaring the names of any donor in 8 years , BSP declared total assets worth Rs. 400.72 crores in the FY 2012-13 out of which they declared immovable assets worth Rs.82.89 crores.

Indian National Congress (INC) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) were earlier found guilty of taking donations from foreign sources by the Delhi High Court. This came into light upon the scrutiny of the contribution reports of the two parties. In view of this, it becomes even more important to have greater disclosure of the

income of political parties to ascertain any vested interest that might influence the party and the candidates who win the elections.

Many cases of bogus companies donating huge sums of money to political parties have also been uncovered. A recent case refers to the contribution reports of the All India Trinamool Congress (AITC). A prominent media report stated that the only contribution to AITC in the year financial year 2013-2014 was made by a company whose legitimacy was questionable.

According to Section 182 of the Companies Act, 2013, no company in existence for less than three financial years can make a donation and the maximum amount that a company can contribute to a political party in a year should not exceed 7.5% of its average net profits during the three preceding financial years. But the media report states that M/s Trinetra Consultant Pvt. Ltd. which contributed to AITC in 2013-14, was registered on April 25, 2011. So, when the company made the contribution on March 31, 2014, it was still 25 days short of the three-year mark.

Further, the media report analyzed that in order to be able to make a contribution of Rs 1.40 crore, the company would have had to make profits of at least Rs 28 crores annually for three preceding fiscal years. During the 2012-13 financial year, the company had registered a loss of Rs 4,121. The performance improved the following year (2013-14) but the net profit was not more than Rs 13,589.

There is a lack of frequent and complete scrutiny of financial disclosures of political parties, i.e. of IT Returns and contributions reports containing details of donors who have contributed more than Rs. 20,000 to a party, by either the IT Department or by the ECI.

Role of the Judiciary

On several occasions, the judiciary has sought to curb this menace of criminalization of politics through several landmark judgments. On 10th July, 2013, the Supreme Court of India, in its judgment of the Lily Thomas vs. Union of India case (along with Lok Prahari v. Union of India) ruled that any MP, MLA or MLC who is convicted of a crime and awarded a minimum of two year imprisonment is immediately disqualified and loses membership of the house. Section 8(4) of the RPA, earlier allowed the convicted members to hold office until they exhausted all judicial remedies. This section was declared unconstitutional and was a major step in electoral reforms and to likely become a deterrent for political parties to give tickets to candidates with criminal records as they may lose their seat immediately upon conviction.

However, this was a threat to the unholy nexus of crime and politics and the government tried to overturn the decision of the Supreme Court of India. The Representation of the People (Second Amendment and Validation) Bill, 2013 was introduced in the Rajya Sabha on 30th August, 2013 which proposed that representatives would not be disqualified immediately after conviction. The Indian government also filed a review petition which the Supreme Court dismissed. This move by the government was vehemently opposed by the civil society. On 24th September, 2013, a few days before the fodder scam verdict, the government tried to bring the Bill into effect as an ordinance. However, Rahul Gandhi, Vice President of the INC, made his opinion very clear by tearing up the ordinance. Subsequently both the Bill and the ordinance were withdrawn on 2nd October, 2013.

Given below is a list of elected representatives disqualified after conviction by a court of law:

Another important judgement given by the Supreme Court in the case of PUCL vs Union of India in which the Supreme Court upheld the citizen's right 'not to vote; or 'None of the above' (NOTA) as a mechanism of negative voting. The court directed the Election Commission to include in the Electronic Voting Machine (EVMs) a button for NOTA and give the voter right to express their dissatisfaction against all the candidates in secrecy.

Nearly 60 lakh voters opted for the NOTA option in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. In the recently held elections in five states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Assam, West Bengal and Puducherry, NOTA count was more than the victory margin in 62 out of 822 constituencies that went to polls. NOTA polled close to 17 lakh votes in these five states.

However, this is only a start and not the end. ADR and other civil society organizations have constantly advocated to include a further step wherein if the NOTA votes are more than the winning candidate votes, then there should be re-election and all the candidates who contested should be disallowed and fresh candidates should be given tickets. This will force the political parties to pick the right candidates and who are capable and have a clean background. Since political parties spend a huge amount of money in election campaigns, this will ensure that they pick their candidates carefully and would help in keeping unscrupulous elements out of the electoral fray.

As per the 2002 judgement referred to earlier, the court ruled that voters' right to information was fundamental and in order to make an informed choice, the court ordered every candidate to submit an affidavit with nomination papers giving correct information about their educational qualification, details of financial assets and importantly, their criminal background. Politicians found a way around this judgment. They left blank columns which demanded information which were uncomfortable. The Supreme Court in 2013 put an end to this practice and ruled that if a candidate left columns blank, then the returning officer could reject the nomination papers.

The Supreme Court has made great strides towards ensuring a cleaner polity, setting up significant barriers to entry to public office for criminal elements as well as instituting workable mechanisms to remove them from office if they are already in power. The same view is echoed by the several committees and commissions in the past which have recommended fundamental changes to laws governing electoral practices and disqualifications. However, the lack of political will in incorporating these recommendations is quite clear and therefore the citizens of this country have to depend upon the Courts and the ECI to enforce these changes.

In the context of the data demonstrating the growing prevalence of criminalization of politics, Supreme Court judgments responding to this growth and the reluctance of political parties to take decisive action to prevent it, reform of the law not only becomes imperative but an urgent necessity.

Solutions

Many felt that Prime Minister Narendra Modi's speech in the Rajya Sabha, back in 2014, in which he emphasized the urgent need to cleanse the Parliament of members with a tainted record through the judicial mechanism, brought with it much reason for hope, placing the ball in the Prime Minister's court. While the Supreme Court opposed this on grounds that fast tracking only a certain category of cases was undesirable, fast-tracking of cases is actually an accepted norm especially since the legislature is an important constitutional body. It is not that the law of the land has not been concerned with the growing criminalization in politics. Section 8 of the RPA, 1951, disqualifies a person convicted with a sentence of two years or more from contesting elections. Yet, it falls short for those under trial even for heinous crimes who continue to contest elections. The irony in the situation is quite blatant, for while under trials, are barred from voting, the case is not the same with MPs and MLAs who are under trial. They continue to hold office until convicted. In this regard, the 20th Law Commission's 244th Report on Electoral Reforms, has felt that disqualification on conviction has proven to be incapable of curbing the growing criminalization of politics. Instead, disqualification must take place at the level of framing of charges for offences that have a maximum punishment of five years or more and where cases have been framed at least a year prior to the date of scrutiny of nomination papers. Moreover in cases where charges have been framed against MPs and MLAs, the trial must take place expeditiously and concluded within a year.

One possible way to cure the Parliament of its criminal elements involves a refusal on the part of political parties to give tickets to candidates with criminal cases. In fact the NOTA option on EVM's was introduced in order to encourage political parties to think before giving tickets to criminal elements. A number of other suggestions have also been proposed ranging from the "Right to Reject" all candidates in a constituency, to making political parties liable for any false declarations made by candidates. It remains to be seen which laws will be implemented to debar candidates with criminal cases to contest elections.

Another way out is the continued role of the civil society in keeping a close check on the Parliament and advocating for a change. Till date, much has been achieved by civil society, ranging from mandatory declaration by contesting candidates of their criminal and financial details, the initiation of the RTI (Right to Information Act), the efforts made to declare political parties as "public authorities", among many others. In 2013, ADR had written to elected representatives across the country, requesting them to voluntarily disclose their Income Tax Returns, a move that was supported by 28 MLAs and MPs. The civil society then is acting. However, the desired goals are far from achieved and will perhaps come through only when the multiple perspectives within the civil society are streamlined into one strong voice, instead of dissipating into different paths.

The role of the citizens in achieving a clean Parliament is perhaps just as significant as any other remedy. The surest way to bring about decriminalization is if voters stop voting for tainted candidates and stop selling their vote in exchange for benefits in cash and kind. It is important for citizens to understand that if they keep electing candidates with criminal records, 'good governance' will be almost impossible to achieve. The ECI as well as civil society organizations such as ADR have been running massive voter awareness campaigns, encouraging people to go out and vote; to vote only after making an informed choice and to not 'sell their vote'. In this digital age, the ability of these organizations to use social media and mobile technologies to their advantage in reaching out to the masses will determine how effectively the citizens can be sensitized to the issue. The role of citizens is rejecting candidates with criminal cases will also be determined by the choices presented to them by political parties, a fact that is further dependent on the extent of transparency in the internal functioning of political parties.

The need for a comprehensive Bill to strengthen political parties has been felt for some time. The Law Commission headed by Justice Jeevan Reddy and the Working Committee to Review the Constitution headed by former Chief Justice, M.N. Venkatachaliah have addressed this issue. A Bill titled ‘The Political Parties (Registration & Regulation of Affairs, etc.)’ was drafted by a committee chaired by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah. Currently there is no comprehensive law regulating the functioning of political parties and the adoption of this Bill would be a step forward.

Political Parties have much to gain in paving the way for transparency and accountability in their functioning. The loss of public trust in the political establishment has a lot to do with the inaccessibility of political parties other than during election campaigns, their opaque finances, and their tendency to allot party tickets to candidates with serious criminal cases. The seriousness that the political community displayed in their election campaigns towards combating the issue of black money and corruption needs to be extended to their own finances and their way of functioning.

* Nilesh Ekka is a Senior Researcher and Akanksha Baldawa is a Senior Programme Associate at Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR)