Grand Targets Without a Roadmap

Is Universal Access to Education Possible?

Ambarish Rai and Srijita Majumder*

About Right to Education Forum

The Right to Education Forum (RTE Forum) is a coalition of around 10,000 organisations working in 20 states across India.

The Forum comprises national people’s movements, prominent educationists, social workers and social activists. It was formed after the enactment of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009 in 2010, for closely tracking and supporting the implementation of the RTE Act. Its structure is federal and it brings together actors at the national, state and district levels that share a common commitment to the implementation of the right to education. The Forum envisions realising the goal of universal education for all through a strong public system of education, funded by the State.

The broad thematic areas of its work include:

- Systemic Readiness and Redressal Mechanism

- Issues of Teachers

- Girls’ Education

- Community Participation

- Quality of Education

- Social Inclusion

- Curbing Privatisation of Education

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected girls. Extended school closures have made girls more vulnerable to gender-based violence, early marriages and child trafficking.

In this article RTE Forum presents a critical analysis of the new education policy.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has been approved and it came after a period of 34 years. The previous policy was adopted in 1986, with a modification made to it in 1992. Since the last policy, considerable progress has been made in the field of school education, the most significant among them being the promulgation of the Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009 (RTE Act 2009), which made elementary education a fundamental right in India. It mandated the State to provide free and compulsory education to all children from 6-14 years of age. For the first time the school system was defined by an Act of Parliament.

This Act also provided for several child-centric provisions like neighbourhood schools, age-appropriate learning and laid down different infrastructural norms which set the benchmark for quality and equity. The RTE Act is the highest stage reached in the evolution of education policy in India. Hence, any education policy must take this into cognisance. Surprisingly, the NEP 2020 mentions RTE Act only a couple of times, that too in passing reference.

The draft NEP 2019 that was released for public comments in 2019 had recommended the extension of the RTE Act 2009 to include children from 3-18 years and this was welcomed across civil societies in India. They felt that it would have been a big step towards the achievement of universalisation of school education. However, much to everyone’s dismay, the final policy is silent on this. The final policy does talk about universal access to education, but without a mandatory mechanism it doesn’t seem possible.

The policy document recommends an overhaul in the entire structure of school education system. The 10+2 structure of the education system which has been in place since the first Education Policy was announced in 1968 based on Kothari Commission’s (1964-66) recommendation will be replaced with the 5+3+3+4 system. The new system will take years to be implemented on ground, in view of the complexity of the current system. In the process, the dislocation and disruption that will result would take years to be stabilised.1 Alongside this, the foundational literacy and numeracy programme aims at making children school-ready before they join class 1. Hence, it is important to look at the dangers of making a child school ready from such an early age.2

The document sets the goal of 100% Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) from pre-school to secondary standards and bringing 2 crore out-of-school children back in schools. While it is a welcome step, the policy lacks a roadmap of how it will be achieved. Similarly, the policy does reiterate that 6% of GDP will be allocated for education, but fails to give a timeline for this. It is important to highlight here that the Ministry of Human Resource Development has deprioritised education to a Category C expenditure (the lowest classification), which will restrict expenditure to within 15% of that budgeted for at least Q1 and Q2 2020-21.3 This shed considerable light into how much the government is willing to allocate for education.

Although, the creation of the Gender Inclusion Fund to promote and strengthen girls’ participation and completion of school education is laudable, the issue of girls’ education is clubbed within the discourse of Socio-Economically Disadvantaged Groups (SEDGs). This undermines the historical and structural barriers that act as roadblocks to girls’ education. As opposed to this, the National Education Policy of 1986, envisioned education as a transformative force which would build women’s self-confidence, improve their position in society and enable them to challenge inequalities that are prevalent in Indian society. The new policy does not see education as a transformational tool to change the disparity in the society and move in the direction of empowerment of girls and a more egalitarian society.4

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected girls. Extended school closures have made girls more vulnerable to gender-based violence, early marriages and child trafficking. Simultaneously, they are also facing the unequal burden of domestic chores and care work. In such a scenario an education policy with a strong gender focus is needed, which is missing in the present document.

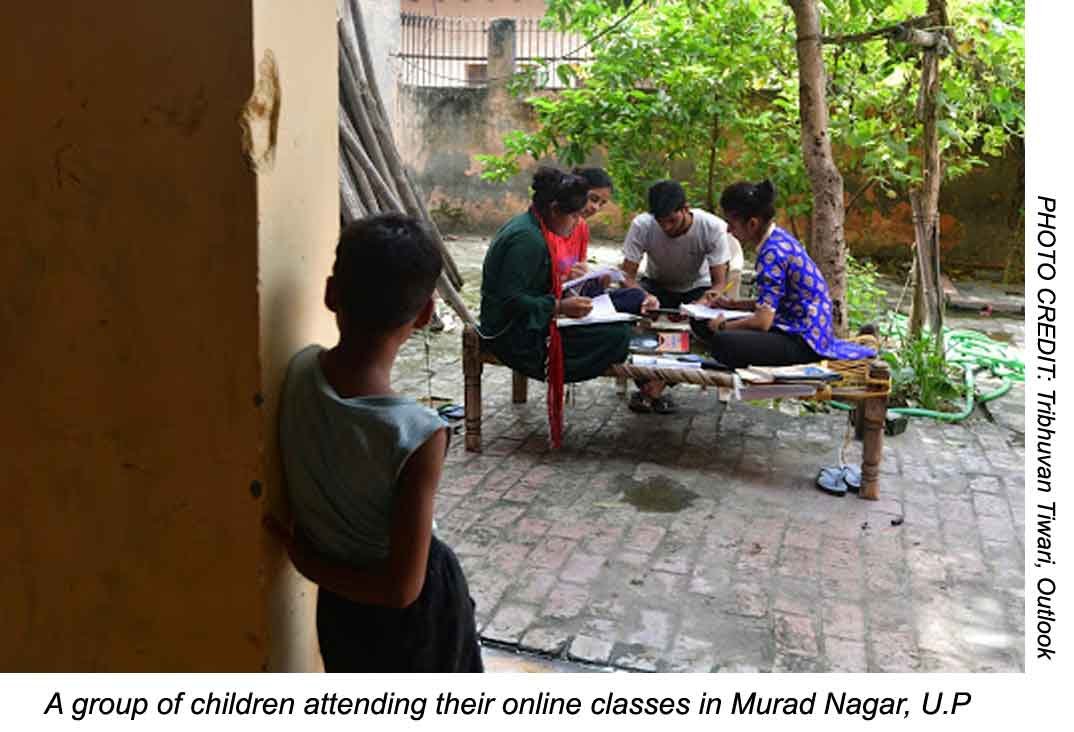

The document emphasises on digital education, which will further deepen the existing segregation in society. Only half of urban households and 14.9% of rural households have internet access.5 A brief study conducted by RTE Forum in 11 villages of Hamirpur district in Uttar Pradesh revealed that out of a total number of 1525 students from 11 schools (from 11 villages), only 252 had someone in the family with a smartphone (16%).

There is a looming fear that while children from urban private schools, with access to digital means, will learn coding, the majority of India’s children, without this facility will be pushed towards child labour and their education would be discontinued.

Out of these 252 students, only 87 responded to work/assignments given by their teachers on the WhatsApp groups. Thus, in reality, only 5% students actually could avail the facility of online education. This digital divide deepens further when it comes to girls’ access to technology. The news of suicides of school-going children, unable to join online classes due to lack of smart-phones, in the states of Kerala,6 Madhya Pradesh,7 Assam,8 Maharashtra9 and West Bengal10 and also the double suicide in Tamil Nadu11 by children who couldn’t face the pressure of online learning, highlight the government’s need for devising alternative forms of distance learning, till the time schools remain closed.

The policy, on one hand, mentions that children from class 6 will be taught the nuances of coding. While, on the other, it says that vocational training on pottery, carpentry and gardening will also begin from the same grade. There is a looming fear that while children from urban private schools, with access to digital means, will learn coding, the majority of India’s children, without this facility will be pushed towards child labour and their education would be discontinued.

The process of school closure under the pretext of rationalisation was first seen in Rajasthan, where closure of schools with small enrolments were recommended. It was soon followed by other states. In Rajasthan, till 2014, as many as 17,000 schools were closed/ merged. Later, 4000 were re-opened owing to public pressure.12 Evidence shows that increased distance due to school closure has led to a rise in drop-outs, particularly among girls.13 The NITI Aayog, as part of its Sustainable Action for Transforming Human Capital in Education (SATH-E) programme, which started in 2018, has closed down nearly 40,000 schools in Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Odisha.14 The National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) validates and legitimises these processes by mentioning the consolidation of school complexes. However, the question remains as to how it’ll be done without impacting education access. Rationalising the distance from 5 to 10 kms, as mentioned in the NEP, will not only have a negative impact on access but also dilute the norms of the RTE Act 2009.

The NEP, in the name of philanthropic schools and Public Private Partnerships (PPP), is laying out the roadmap for the entry of private players in education. This will further commercialise education, exacerbating existing inequalities, while girls from marginalised communities will remain alienated.15

This policy is also silent on the Common School System, which was first recommended by the Kothari Commission (1964-66) and reaffirmed in the National Education Policies in 1968 and 1986. One way to remove the discrimination in the school education system is to introduce a Common School System (CSS) in the country which ensures a uniform quality of education to all the children.16

*Ambarish Rai is National Convenor and Srijita Majumder is Research and Advocacy Coordinator, Right to Education Forum.

( Endnotes )

- ( 1 ) RTE Forum. RTE Forum’s comments on the Draft National Education Policy. Retrieved September 26 , 2020 from https://bit.ly/3jrwiAF

- ( 2 ) Prof Krishna Kumar. IIC Lectures. (2020, September 25). The National Education Policy 2020, Retrieved September 26 , 2020 from https://bit.ly/34rGRiQ

- ( 3 ) RTE Forum. Building back better: Gender-responsive strategies to address the impact of COVID-19 on girls’ education. Retrieved October 26, 2020 from https://bit.ly/35u3zq0

- ( 4 ) RTE Forum. Working Paper on Girls’ Education

- ( 5 ) RTE Forum. Building back better: Gender-responsive strategies to address the impact of COVID-19 on girls’ education. Retrieved October 26, 2020 from https://bit.ly/35u3zq0

- ( 6 ) Koshy, Sneha Mary. (2020, June 2). Unable To Join Online Classes, Kerala Schoolgirl Commits Suicide: Cops. NDTV.com. Retrieved September 26, 2020 from https://bit.ly/31EwHJR

- ( 7 ) Pandey, Sachin. (2020, June 24). MP school girl ends life since parents didn’t buy her smartphone for online classes. Hindustan Times. Retrieved August 17, 2020 from https://bit.ly/37EFUG4

- ( 8 ) Edex Live Team (2020, June 24). Unable to attend online classes and exams, Class 10 student commits suicide in Assam. Edexlive.com. Retrieved September 29, 2020 from https://bit.ly/37LnOSL

- ( 9 ) Express News Service (October 1, 2020) Maharashtra: No smartphone to attend online classes, 15-year-old girl commits suicide. The Indian Express. Retrieved September 28, 2020 from https://bit.ly/31HCHBD

- ( 10 ) Newsroom Team (2020, June 22). With no computer or smartphone, 16-year-old student commits suicide after failing to attend online classes. Rajasthan. MirrorNowNews.com. Retrieved September 20, 2020 from https://bit.ly/3kvvkEW

- ( 11 ) Nath, Akshaya. (2020, September 3). Tamil Nadu: Two student suicides raise concerns over online classes. India Today. Retrieved September 9, 2020 from https://bit.ly/34stAqd

- ( 12 ) Bishnoi, N. (2019, May 23). 4,000 schools may be reopened in Rajasthan. Hindustan Times. Retrieved September 29, 2020 from https://bit.ly/3ktW8FH

- ( 13 ) Rao, S., Ganguly, S., Singh, J., & Dash, R. R. (2016). School Closures and Mergers: A Multi-state Study of Policy and its Impact on Public Education System in Telangana, Odisha and Rajasthan. Save the Children

- ( 14 ) Minister of Human Resource Development, Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’, in response to a question in the Lok Sabha. Retrieved October 26, 2020 from https://bit.ly/3orcp0d

- ( 15 ) Bhatt, N. (2020, September 2). Examining India’s new education policy through a gender lens. Devex. Retrieved September 29 , 2020 from https://bit.ly/35D2fRC

- ( 16 ) RTE Forum. RTE Forum’s comments on the Draft National Education Policy. Retrieved September 26 , 2020 from https://bit.ly/3jrwiAF

NEXT »

Can Education be Left to Market Forces? >>

By Anita Rampal