Policing in Conflict-Affected Regions

SPIR 2020-21 (VOLUME I)

POLICING IN CONFLICT-AFFECTED REGIONS

Summary and Key Findings

The Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2020-21 (Volume I): Policing in Conflict-Affected Regions, gathers and evaluates original data on policing under extraordinary circumstances. It has been divided into two parts: First, a study of policing in conflict-affected areas and second, a study of policing during the Covid-19 pandemic. The studies present policy-oriented insights into everyday working of the police in India. It is brought to you by Common Cause and the Lokniti Programme of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) and is backed by our philanthropic partners, Tata Trusts and the Lal Family Foundation.

The first part of the SPIR 2020- 21 is focused on districts and states affected by some form of conflict, extremism, or insurgency while the second part looks at the preparedness of the cops against disasters in general and health emergencies in particular. Both the studies combine perceptions and performance about policing, in essence, a continuation of the SPIR 2018 and 2019. The earlier reports were focused on citizens’ trust and satisfaction with the police and their adequacy, attitudes and working conditions. The present study also surveys both the police personnel and common citizens using separate teams and questionnaires in different geographies.

It is well-known that everything about policing at the conflict areas—from jurisdictions to the line of command—is affected by the presence of the Army or the para-military forces under stringent legal provisions. It is equally true that the presence of armed underground outfits changes the nature of politics and society in conflict areas. This report aims to understand how policing is carried out in disturbed areas and if there are any lessons in it for policymakers. The study also looks at how conflict situations affect normal crime, its investigation and resolution. It unravels the attitudes of police personnel, their working conditions, training and preparedness as also their relationships with various stakeholders of the conflict.

For this study, a total of 6,881 individuals (2276 police personnel and 4605 civilians), across 27 districts in 11 states and Union Territories were surveyed. The conflict-affected districts were selected from amongst the list of disturbed areas provided by the Ministry of Home Affairs and where incidents of violence have been reported consistently in the presence of the Army or the paramilitary forces. The report also analyses official data released by government agencies. In this section, we present some of the key findings from the report. For the sake of brevity, the findings have been thematically divided and presented in bullet points. For a more detailed understanding, please visit https://www.commoncause.in to view the entire report.

Analysis of official crime data in conflict states

The first chapter, ‘India’s Conflict in Numbers’ analyses official data on conflict states. It examines the existing quantitative literature on the subject and presents a bird’s eye view of the official statistics collated by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB).

• The rates of cognisable crimes in the conflict-affected districts and states surveyed are lower than the national average, when seen as an average of five years. While the average rate of IPC crimes in the selected districts is 178 crimes per lakh of population, the corresponding all-India figure is 237 crimes per lakh. Assam, however, has a significantly higher crime rate than any other selected state or the national average, with 328 IPC crimes per lakh of population.

• The conflict-affected districts have an over four times lower rate of 33 SLL (Special and Local Laws) crimes per lakh of population against the all-India average of 146 SLL per lakh.

• The rates of violent crimes (murder, grievous hurt, kidnapping and abduction) are much higher in the conflictaffected districts compared to the national average. While the national

rate of kidnapping and abduction is 7 per lakh population, the corresponding rate for the selected districts is 10 per lakh. In the insurgencyaffected states, the rate is thrice the national average, at 21 incidents of kidnapping and abduction per lakh population.

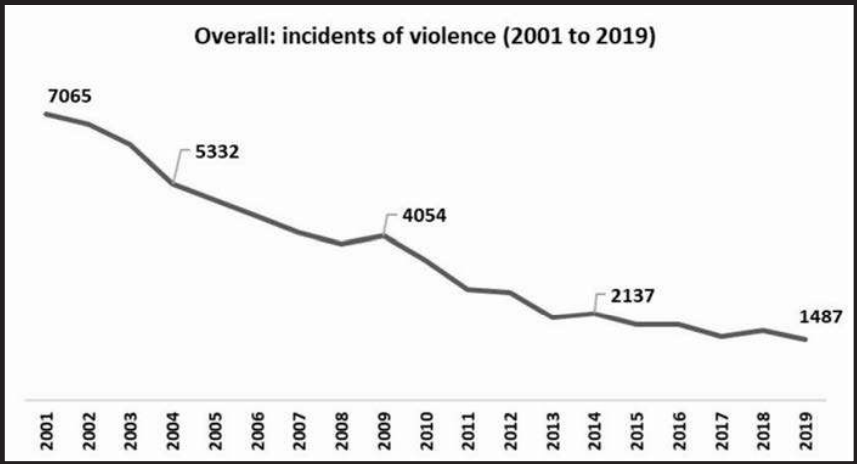

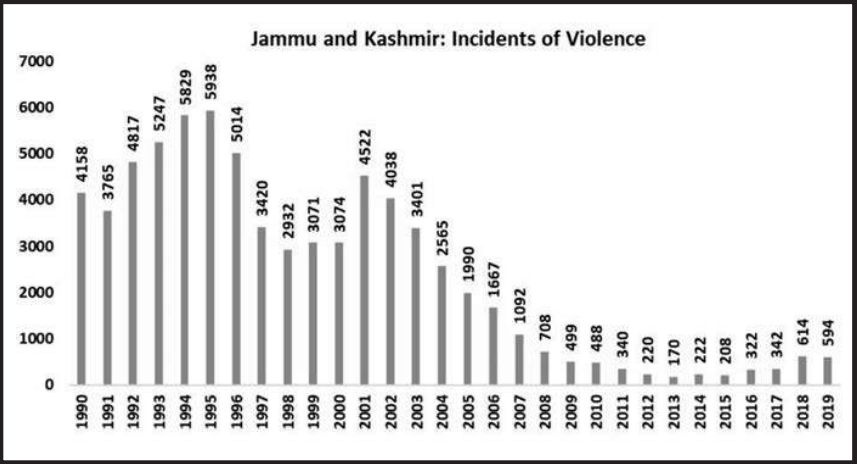

• Between 2001 and 2019, over 68,500 incidents of violence were reported from Jammu and Kashmir region, northeastern states and Left-Wing Extremism (LWE)- affected regions of the country in which 23,283 civilians and security force personnel lost their lives. About 75 percent incidents were reported in the first decade i.e., between 2001 and 2010 and nearly 45 per cent of them were reported in the first five years of 2000s.

• The level of violence and tension in J&K region has

• Post 2012, insurgency in the northeastern states has declined rapidly and the violent incidents have dropped from 1025 to 223 in 2019. In 2019, as many as 21 civilians and four security personnel lost lives in the North East region compared to 97 and 14 respectively in 2012.

• Post 2012, insurgency in the northeastern states has declined rapidly and the violent incidents have dropped from 1025 to 223 in 2019. In 2019, as many as 21 civilians and four security personnel lost lives in the North East region compared to 97 and 14 respectively in 2012.

Perceptions about conflict

The second chapter examines the attitude of the police and the common people towards the conflict, their perceptions about the violent groups and the state’s response to them. It also attempts to understand the citizens’ levels of trust in the parties of the conflict and brings out the range of opinions on the problems of the regions and how to deal with them.

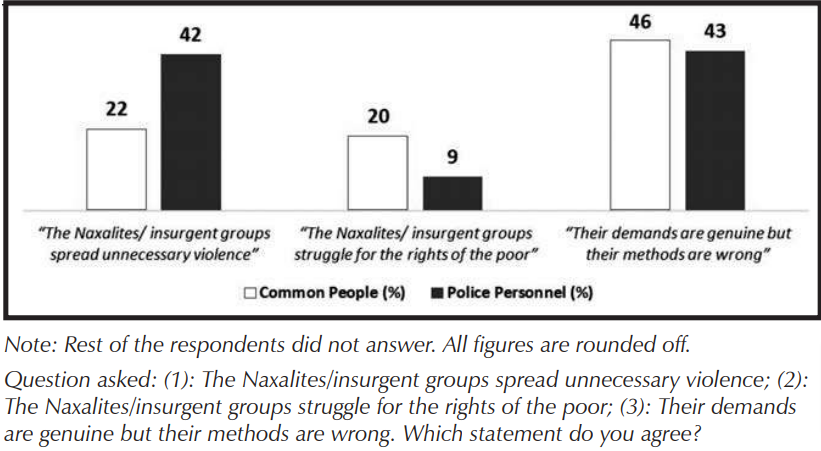

• In conflict-affected regions, 46 percent common people and 43 percent police personnel believe that the demands of Naxalites/insurgents are genuine, but their methods are wrong. The scheduled tribes are more likely to believe so, with one out of two ST persons agreeing with the statement.

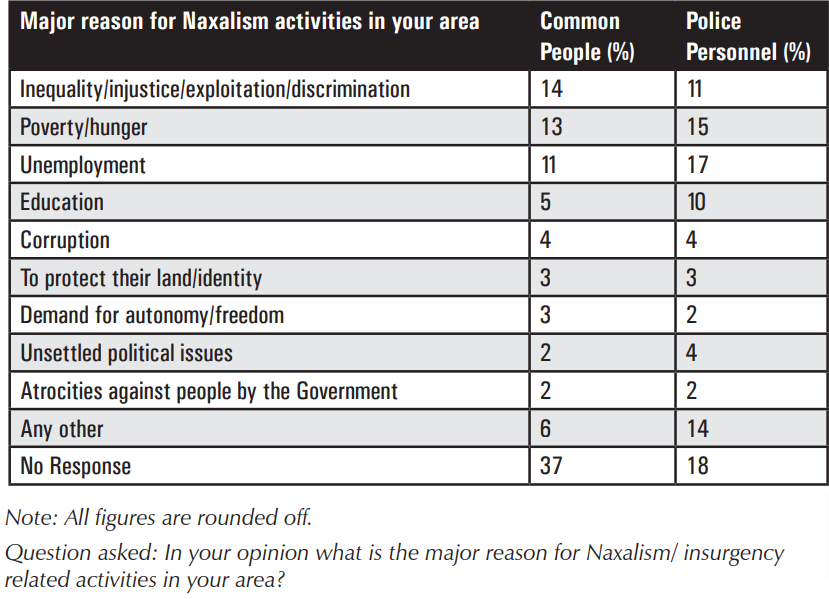

• According to common people, inequality, injustice, exploitation, discrimination are the biggest reasons behind Naxalite/insurgent activities, followed by poverty and unemployment.

Thirty-seven percent common people fear physical assault by the Naxalites/insurgents; 35 percent by the police; 32 percent by the paramilitary forces/Army

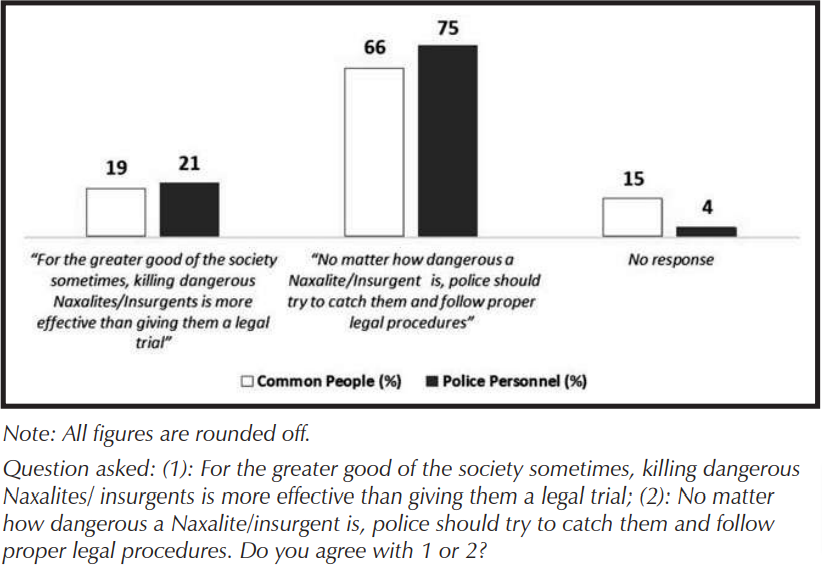

• One out of five common persons as well as police personnel feel that killing a dangerous Naxalite/insurgent is better than a legal trial. Support for direct elimination was higher in LWE-affected regions among both the police personnel and common people as compared to insurgency-affected regions. One fourth of the police personnel and one-fifth of the people in the LWE-affected regions recommended the elimination of dangerous Naxalites for the greater good of the society. Only 15 percent police personnel and 18 percent common people supported the direct elimination of insurgents.

• Fifty-nine percent common people and 50 percent police personnel believe that it is wrong to ignore human rights in the name of national security. However, 34 percent common people and 42 percent police personnel also fully agree with the statement that the police should eliminate criminals while dealing with Naxalites/ insurgents.

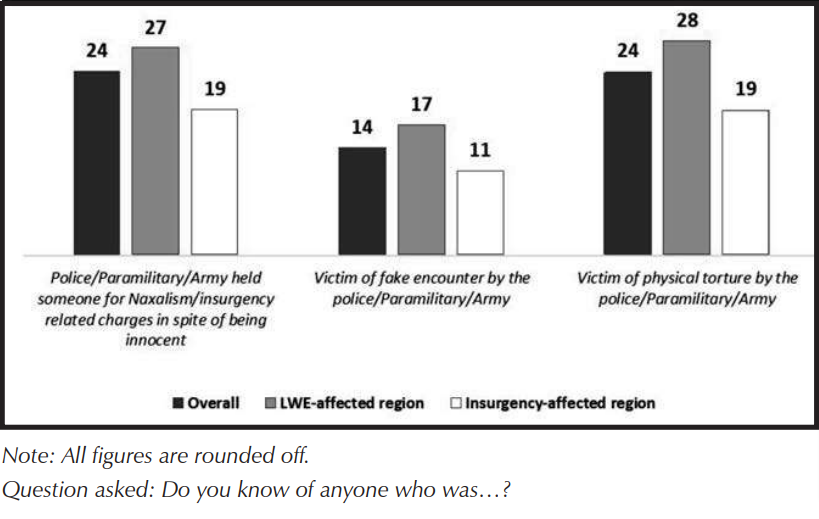

• Nearly one-fourth (24%) of the people knew someone who was a victim of physical torture either by the police or paramilitary/armed forces. The same proportion (24%) of people said that they knew about an innocent person being held by either the police or the paramilitary forces/ Army for Naxalism/insurgencyrelated charges.

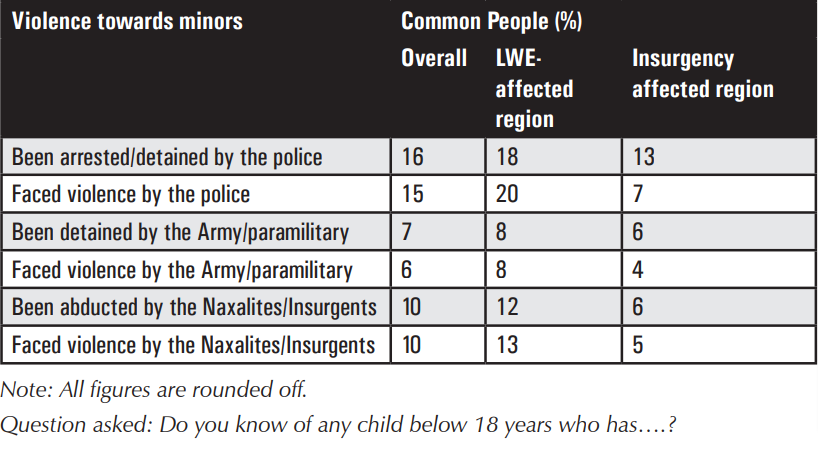

• People living in the LWEaffected districts were more vulnerable to violence by the police and paramilitary forces, as compared to people living in the insurgency affected districts. One out of five people from the LWE-affected regions personally know of cases of physical torture by the police; one out of five people from LWE-affected regions also know of cases of minors being arrested/detained by the police or of police being violent towards minors.

Police’s perceptions of the legal framework

Devoted to the adequacy of the police and security forces, their training, resources, equipment, and the legal cover available to them, the Third Chapter examines their overall preparedness in the conflict regions. It also looks at the perceptions of the common people about the abovementioned challenges. It further delves into the perceptions of the police personnel about the laws which are commonly used in conflict regions, such as the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (UAPA), the National Security Act, 1980 (NSA) etc.

• A big majority of the police personnel surveyed (60%) believe that strict laws like UAPA, NSA etc. are important for controlling Naxalite/insurgent activities. Significantly, however, only 30 percent of the common people believe so.

• Forty-two percent of the common people from the insurgency-affected areas of North East believe that security laws such as UAPA are very harsh and should be repealed.

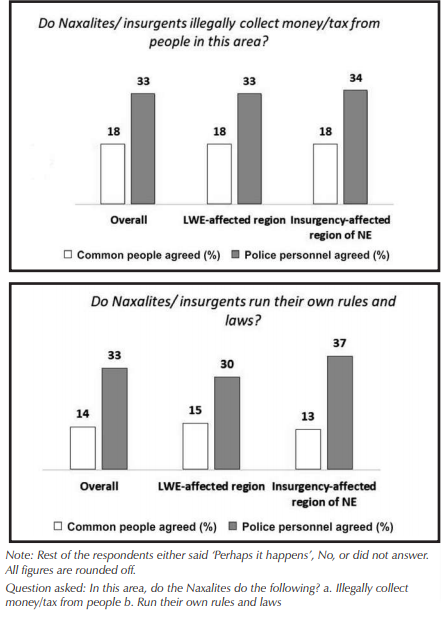

• One in three police personnel believe that Naxalites/ insurgents run a parallel taxation or justice system. However, only 18 percent and 14 percent common people respectively believe that Naxalites/insurgents run a parallel taxation system and a parallel justice/law and order system.

Discrimination by the police

Chapter four analyses the relationship between the police and people in conflict regions. It examines peoplepolice confrontations around public protests and civilian demonstrations. It also looks at the perceptions around fairness and discrimination by the police and the sense of fear and lack of trust among the civilians regarding police surveillance and excessive use of force.

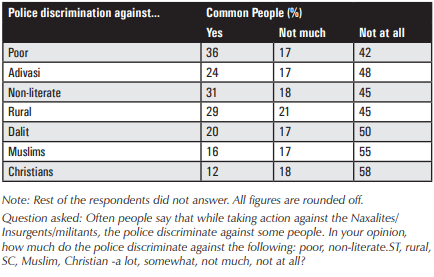

• Thirty-six percent common people believe that the police discriminate against the poor in their drive against Naxalites/ insurgents. Among the communities, Adivasis (24%) face more discrimination followed by Dalits (20%) and Muslims (16%)

• Amongst the common people from the LWE-affected regions, 40 percent believe that during criminal investigation the police would favour a rich person against a poor person, 32 percent feel that they would favour an upper caste against a Dalit; 22 percent feel that they would favour a non-Adivasi against an Adivasi; and 20 percent feel they would favour a Hindu against a Muslim.

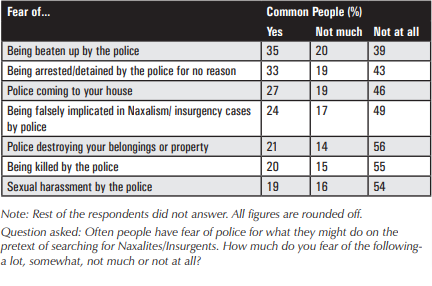

• About one out of three common people are afraid of being beaten up by the police or being arrested or detained by the police for no reason; Nineteen percent of the people from the insurgencyaffected regions have a lot of fear of the police.

People’s perceptions about the police vis-à-vis the armed forces

• People in conflict regions have different opinions about and experiences of dealing with different law enforcement agencies deployed there. Chapter Five, ‘Perceptions about the police vis-à-vis paramilitary forces or the Army’, brings these out through a survey of both the common people and police personnel. It tries to capture the perceptions of the local people and police personnel, levels of their trust in each other and differential treatment given by the government to different agencies.

• A significant majority of the common people (60%) believe that for their safety and security, they need the state police more than the paramilitary forces/Army; Common people who feel unsafe living in the region are more likely to believe so.

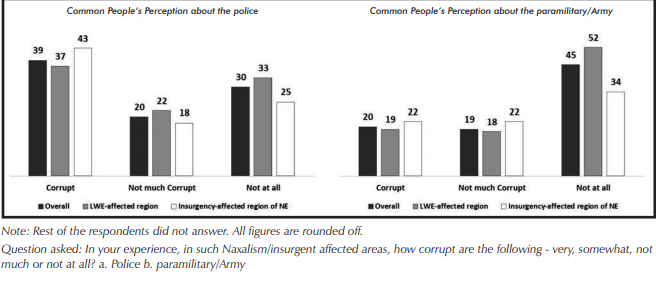

Nearly two out of five people (39%) believe that the police is corrupt in conflict-affected regions, while 20 percent believe that the paramilitary forces/Army is corrupt in such regions. This difference in perception was true for both the insurgency and LWE affected regions, although the difference was starker in the former. The poorer assessment of the police vis-à-vis the paramilitary forces/Army on the corruption parameter could again be attributed to higher frequency of daytoday interaction between the police and common people, compared to the paramilitary forces/Army. Owing to frequent interactions, the chances of people having experienced police corruption are higher.

Working conditions of the police

Chapter 6, ‘Posting to a Conflict Region: Opinions of Police and Common People’, captures the risks (both physical and mental), anxieties, and special needs of the personnel deployed in these regions, by their own assessment.

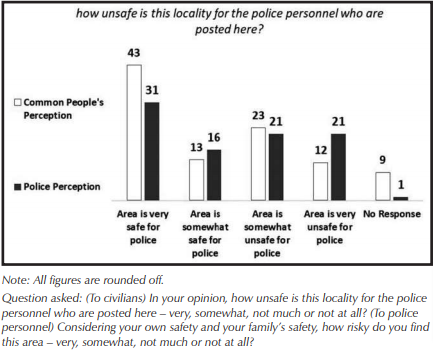

• Common people living in conflict regions are more likely to consider the area as being safe for police, as compared to the perception of safety of the police personnel themselves. At the same time, common people are also more likely to consider the region as being safe for their own living– 70 percent believe that the area is very safe for living.

Difference in perception regarding the safety of the area between ST respondents and respondents belonging to other caste groups, particularly in the LWE-affected areas was clearly noticeable. Nearly 73 per cent Non-ST respondents from LWE region reported that the area is very safe for living. However, only 53 per cent ST felt that the area is safe for living. This could be on account of the fact that the both Left-Wing Extremism and insurgency activities have usually been more rampant in tribal areas than others. Hence, it is only natural for tribals to be more likely to feel unsafe, being located at the centre of the conflict.

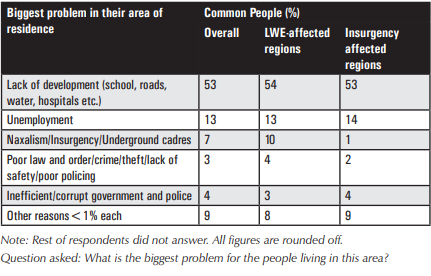

• A majority of the people (53%) believe that lack of development is the biggest problem in the region. However, 13 per cent people living in the conflict area reported that unemployment is the biggest problem for them.

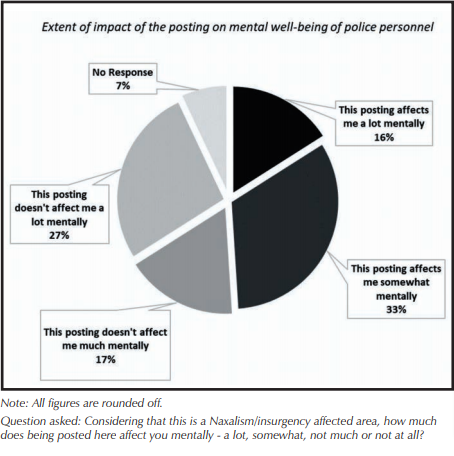

• When asked ‘how much does being posted in a Naxalism/ insurgency affected area affect you mentally?’ 16 per cent police personnel answered ‘a lot’. Overall, one out of two police personnel (49%) admitted that their current posting is affecting their mental well-being adversely.

Crime in conflictaffected regions

Chapter 7 talks about common crimes occurring in the conflictaffected regions and their frequency. It analyses the opinions of the people and police on whether crimes in conflict-affected areas have increased or decreased. It also discusses in detail the extent to which the ongoing conflict affects general policing in these regions and some important steps suggested by the police personnel to control crime in these specific regions.

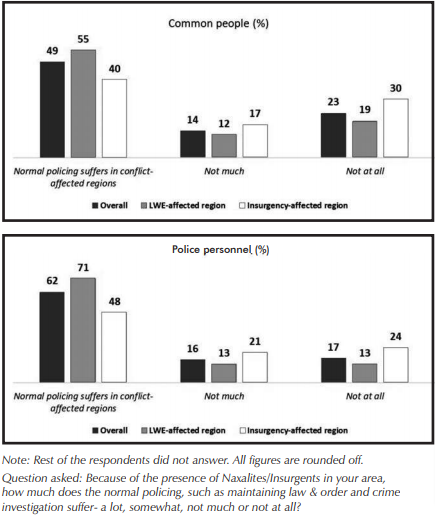

• Police personnel and common people from LWE-affected regions are more likely to believe that normal policing suffers because of conflict

• Hindu upper castes and OBCs were more likely to contact the police, while Adivasis were more likely to be contacted by the police. Nearly seven out of 10 Hindu upper castes and OBCs reported that they contacted the police. Whereas, 22 percent Adivasi respondents and 24 percent people from other religious minorities living in the conflictaffected regions said that police had contacted them. Similar trends were found in SPIR 2018 as well.

Strategies for resolving the conflict and the ways ahead

Chapter 8 discusses the perception of the citizens on what should be the best way to control the conflict, while highlighting the key steps required for improving the present situation. It further looks at the perception of police personnel on the efficiency of their local colleagues. It also studies the perception of the common people on issues of increasing the strength of the paramilitary forces or the Army in such regions.

• An overwhelming majority of police personnel (75%) and common people (63%) felt that addressing development and providing better facilities in the area would be very useful for reducing the conflict.

• Nine out of 10 police personnel believe that increasing the number of police personnel would be a useful measure for reducing Naxalism/Insurgency activities, whereas only about 75 per cent common people agreed with this.

• More than one out of three police personnel (35%) feel that the government should improve the working conditions of the police. Almost a quarter also said that the government should ensure that they receive adequate training and facilities to be able to handle conflict situations.

• When police personnel were asked who is better suited for or is more effective in conflictaffected areas — those from the same district or those from another — they were three times more likely to prefer the former. While 40 percent said a local police person would be more effective, only 14 percent preferred an outsider. However, 41 percent police personnel answered that it doesn’t matter if the police person is from the same district or another. They felt that both will be equally efficient in their job.

The online launch of the Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) 2020-2021, (Volume 1), Policing in Conflict-Affected Regions, took place even as a furious second wave of the coronavirus devastated the country. Despite several of our colleagues getting infected with the deadly virus, we managed to organise the online release of the report on April 19, 2021. Owing to the swelling numbers of attendees, we had to stream the release event on both Zoom and YouTube. Representatives from the civil society, academia, activists, retired and serving police officers and students

attended the event. The report release occasion also featured a Keynote Address on ‘Is the Rule of Law Backsliding in India? Our Challenges for the 2020s,’ by Justice Madan B Lokur as well as a panel discussion on ‘Can Extra-judicial Killings be the State Policy?’ Participants of the panel discussion included Mr. Prakash Singh, former DGP and Chairman, Indian Police Foundation, Ms. Patricia Mukhim, Editor, The Shillong Times, Dr. Sudhir Krishnaswamy, VC, NLSIU, Bengaluru, and Dr. Meeran Borwankar, former DG and Police Commissioner.

The edited excerpts of the keynote address and panel discussion are given here:

People have the right to protest. How do the police curb the right to protest or what are the checks on the right to protest?

NEXT »