Roadblocks to Ethical Governance

Who Will Hold the Public Authorities to Account?

Shambhu Ghatak*

The Right to Information Act in 2005 is considered to be a bold step towards making the public authorities accountable and transparent to the citizens of India. Under the RTI Act, one can seek information (as permitted by its various provisions) from a public authority by writing an application in a prescribed format along with a fee (no fee required for below poverty line citizens). If one is not satisfied with the information provided by the Public Information Officer (PIO) in the first attempt, the Act outlines a proper process for following up. However, there are provisions in the RTI legislation itself, that requires the public authority to disclose information on its own in the public domain so that the citizens can access information without even the need to demand for it. 1

The booklet RTI Act: Authentic Interpretation of the Statute (first printed in 2016), by Shailesh Gandhi and Pralhad Kachare, says that Section 4 of the RTI Act is the core and guiding framework of the legislation to ascertain good governance.2 Section 4(1)(a) of the Act mandates good governance by way of providing information to the public and maintaining records, duly catalogued and indexed to make them accessible easily to the people. In addition, the legislation requires every public authority to computerise its records and upload them so that they can be accessed whenever required. Put simply, the RTI legislation is a mandate for e-governance implementation in letter and spirit, write Gandhi and Kachare.

Besides that, under Section 4(1)(b) of the RTI legislation, every public authority is required to upload information in the public domain on a proactive basis. The authors add that the means and methods for the dissemination of information, could include the following:

- Notice Board;

- Office Library;

- Kiosk in office premises or through web portal;

- Through Newspapers, leaflets, brochures, booklets;

- Inspection of records in the offices;

- System of issuing of photocopies of documents;

- Printed manuals to be made available;

- Electronic storage devices;

- Website of the Public Authority, e-books, CD, DVD, Open Source Files, Web Drives;

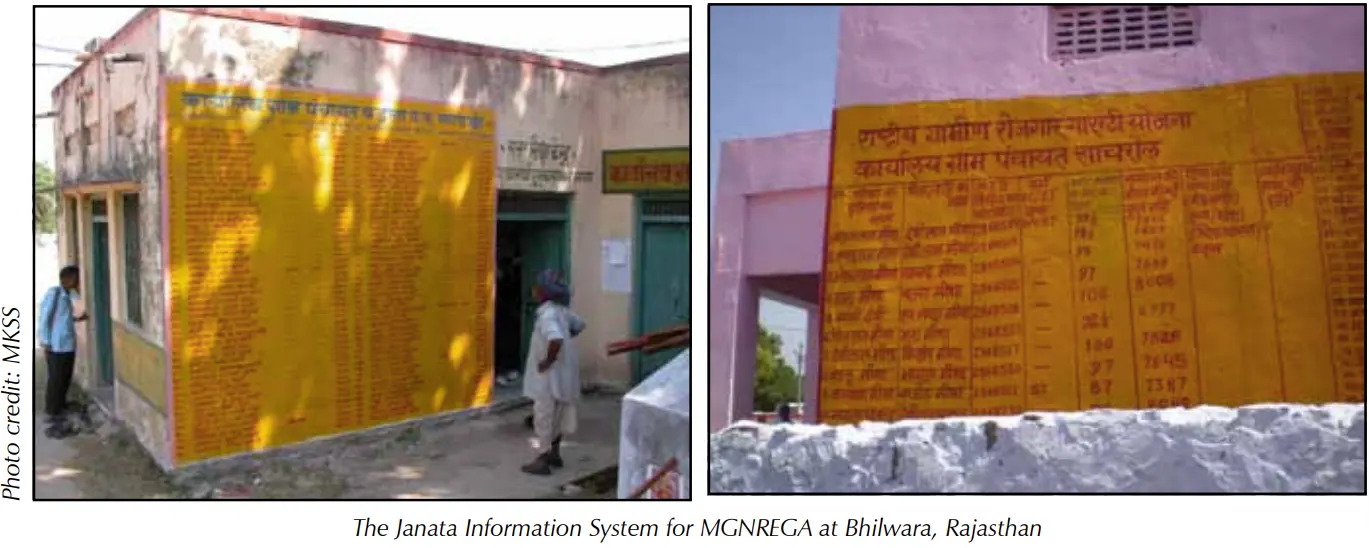

- Painting data on the walls of buildings as is being done in some places in the case of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (also termed as Janata Information System by RTI activists in Rajasthan);

- Social Media;

- Drama and Shows;

- Exhibition; and

- Other means of advertising.

We can conclude that there are two sides to the information story. Common citizens appeal for disclosure of information from public authorities through the processes outlined in the Act. But public authorities are also mandated to share relevant information voluntarily. If they take initiatives to share records held by them in a transparent and efficient manner, the need for filing individual RTI applications reduces dramatically, thereby lessening the burden on PIOs and other officers.

Auditing Proactive Disclosures under the RTI Act

The Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the policy formulator and watch-dog of the government, had directed all the public authorities in the country, vide its order dated April 15, 2013, to ensure regular audit of mandatory disclosures by a third party.3

A report, ‘Transparency Audit: Towards an Open and Accountable Government’ (published in 2015), was prepared under the auspices of the Central Information Commission (CIC). It outlined the framework of conducting disclosure audits to verify and authenticate disclosure of information. An evaluation of disclosure by public authorities (although transparency audit pro-forma was sent to 2,092 public authorities in total, just 838 such entities i.e. 40 percent responded till October 31, 2018) through their websites, was done by former Chief Information Commissioner AN Tiwari and former Information Commissioner MM Ansari in 2018. It revealed that certain vital information was not fully displayed on the official websites of various public authorities. The missing information mostly came under the following categories:

- Decision-making process, the delegation of powers, duties, and responsibilities of officials and the system of compensation paid to them;

- Information relating to consultation with public on the proposed major policy decisions, as required, are not available;

- Minutes of meetings of various committees and boards, details of the relevant Acts, rules, instruments, manuals, office orders, custodians of various categories of documents held by the organisation;

- Policy on transfer and posting of senior officers deployed at important and sensitive places;

- RTI applications and appeals received and their responses, details of Public Information Officers, Appellate Authority, Nodal Officer and other facilities available to citizens for obtaining information;

- Details of domestic and foreign visits undertaken by the senior officials;

- Details of the mechanism to redress grievances of affected persons, mainly employees, clients, and customers;

- Discretionary and Non-discretionary Grants and details of the beneficiaries of subsidy;

- Criteria/ guidelines for allocation and utilisation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds by the Public Sector Enterprises;

- Sources and methods of funding political parties or identification of donors; and,

- Details about Public-Private Partnerships and outcomes of such ventures.

It is only when governmentsponsored reports or publicly collected data are placed in the public domain that independent domain experts are able to scrutinise them

It is now widely known that despite RTI being in place, public authorities do not always give out information proactively, and even on requests. Media reports indicate that in the past, even the Comptroller and Auditor General had to take recourse to RTI in order to procure information necessary for effective audits of government finances and decision-making.4 The primary reason for this, as pointed out, is because “while Section 18 of the CAG (Duties, Powers and Conditions of services) Act 1971 provides access to the records and accounts and empowers Audit to inspect any offices of accounts under the state or central government, it doesn’t provide any enforcement powers to CAG to ensure compliance by auditee to his request for information within a reasonable time.”5

Examples of Violation of Section 4 of the RTI Act

On many occasions, it has been found that various provisions (or sub-sections) under Section 4 of the RTI legislation have been violated. I will discuss here some of the violations by public authorities that have taken place in recent as well as the not so recent past.

Availability of information in local languages

Section 4(4) requires that public authorities consider local languages, among other things, to communicate information. However, more than a handful of public authorities violate this provision. Public sector banks are one of the violators. The dominant language present for customer interface on the website/app of most public sector banks for Internet Banking is English. While an Indian banknote displays its denomination in 15 out of the 22 official languages, there is only one language (or at the most Hindi besides English) in the web interface for Internet Banking.6 The language barrier is an obstacle for financial inclusion in a digital economy, which India aspires to be. Even if someone is proficient in a regional language (other than English or Hindi), the language barrier is an obstacle in Internet Banking. There are plenty of websites related to various public authorities, where the only language for citizen’s interface or making complaints is English. One such example is the Customer Login (to register cybercrimes) for the National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal (https://bit.ly/3eidgfU). The Life Insurance Corporation of India’s (LIC) customer e-service portal’s interface languages are also only English and Hindi (https://bit.ly/3yPXn9V).

If public authorities take initiatives to share records in a transparent manner, the need for filing individual RTI applications reduces dramatically

Public consultation for policy formulation

Section 4(1)(c) and (d) require public authorities to proactively disclose relevant facts while formulating policies and also provide reasons for their decisions. 7 Section 4(1)(b)(vii) mentions that “the particulars of any arrangement that exists for consultation with, or representation by, the members of the public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof” needs to be published by the concerned public authority.

The violations of some of these sub-sections, fully or partially, can be understood in the context of events leading up to the promulgation of the three Farm Ordinances (later introduced as Farm Laws in September last year). Media reports reveal the outcome of queries made by RTI activist Anjali Bhardwaj to the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, on details of stakeholder consultations prior to the announcement of the Farm Ordinances. The Union Agriculture Ministry could not provide any record of pre-legislative consultations.8 In one RTI application, she sought details from the Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers’ Welfare (under the Agriculture Ministry), including the website address where the farm reforms bills/ Ordinances had been placed for pre-legislative consultations. In another RTI application, filed before the same department under the Agriculture Ministry, she asked for the dates and names of attendees of consultative meetings, copies of the minutes of the meetings, and lists of the states, experts and farmers’ groups consulted before enacting the three farm laws.9 None of the information officers were able to provide the details sought by Bhardwaj.

Thus, we see that the central government not just violated Section 4 of the RTI Act, it also did not go for a proper pre-legislative consultation while bringing in the farm laws, as is required under the Pre-Legislative Consultation Policy (PLCP) 2014.

Access to government documents and data

There was a time when the country’s statistical system for survey and data collection (primarily the National Sample Survey) was considered one of the best in the world.10 This doesn’t hold true anymore, given the recent spate of events. Although the policies of past governments were to some extent guided by evidence, particularly for certain pro-poor schemes (the Consumption Expenditure Survey (CES) data was used to estimate the proportion of below-poverty-line population in order to check whether the pro-poor welfare schemes/programmes are making any impact on poverty reduction), there was much to be desired. There have been times when data collection did not take place periodically, as was required. Even when the data was collected and analysed by government-appointed experts and statisticians, their reports were not placed in the public domain, including websites. It is only when government-sponsored reports or publicly collected data are placed in the public domain (websites/ social media), that nongovernmental or independent domain experts (including economists and statisticians) are able to scrutinise or question the gaps and serious lacunae.

Let’s look at the all-India Household Consumption Expenditure Survey. Although public money was used for conducting the survey, analysing data and preparing report/s, the Centre decided not to release the latest report/s as well as the unit-level data in the public domain. It was only after some of the key results of the leaked CES 2017-18 report got published in the media that citizens woke up to the government’s efforts of sweeping the survey results (by the National Statistical Office, erstwhile National Sample Survey Office) under the carpet.11 Based on the CES done by NSO, income poverty was calculated for the last time in 2011-12.

Embarrassed by the CES media leakage, the 75th round of survey data was deemed unfit for constructing the new income poverty line and measuring the latest income or expenditure-based poverty. Owing to data discrepancies and issues about data quality, the monthly per capita consumer expenditure data pertaining to 2017-18 was not used by the central government.12 Placing the CES results and data for 2017-18 in the public domain would have allowed independent experts to cross check the government’s claim of poor quality data.13 One should note here that the CES is not just an invaluable analytical and forecasting tool, it is actually used by the government in rebasing the gross domestic product (GDP) and other macro-economic indicators.14

Similar to the CES, the Report of the High Level Committee on Socio-Economic, Health and Educational Status of Tribal Communities of India, was allegedly kept under wraps by the central government back in 2014.15 Although the tribal community report was commissioned by the former Prime Minister’s Office in August 2013, it is alleged that the new government coming to power in 2014 had buried it.16 The highlevel committee headed by Virginius Xaxa submitted that report to the Prime Minister’s Office in May 2014.17 No action was taken later on the basis of the recommendations made by the Xaxa Committee report.

Availability of data in open/machine-readable format

The Open Government Data (OGD) Platform India – data.gov.in – supports the government’s open data initiative.18 Although the government’s open data policy is all about providing proactive access to government owned shareable data, along with its usage information in open/machine-readable format, one is left wanting more. In fact, one finds that websites of various ministries and departments sometimes violate the open data policy in the context of sharing relevant information in the requisite format. There is official acknowledgement that the open data policy is pursued in order “to increase transparency in the functioning of government.” However, one finds that surveys are not conducted by many public authorities on a regular basis, and data (both administrative as well as survey) is not released in the public domain consistently. Even when data is released in the public domain, it may not depict the true picture as it is suppressed or manipulated to avoid public criticism and embarrassment.

Take a look at the administrative data on suicides provided by the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) annual publication Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India. There are many studies questioning the NCRB suicide numbers. For instance, compared to a Lancet study (2012) estimates, the NCRB underreported suicide deaths among men by at least 25 percent and women by at least 36 percent in 2010. There were several under-reported suicide deaths among women and men aged 15-29 years, and also among women aged 60 years or older.19 Although a “Search by Table” option exists on NCRB’s website (https://bit.ly/3yTKhJ4), to facilitate accessing the ADSI data from 1953 onwards, the data is available only in Portable Document Format (PDF) and not in open/ machine-readable format, such as XLS, XLSX, CSV, and JSON. Thus, it is difficult to readily use the information/ data for visualisation.

The data in the annual reports of various ministries of the central government (such as the Ministry of Rural Development, (https:// bit.ly/3momPOM) is not available separately in open/machine-readable format, such as XLS, XLSX, CSV, and JSON, which could be used by policy researchers and data enthusiasts.

Besides conducting third party auditing of proactive disclosure by public authorities, individuals, civil society organisations and private bodies can pursue such exercises on their own

For some central schemes like the MGNREGA, the Management Information System (MIS) data i.e., the administrative data (https://bit.ly/3snz6qJ) is available for national and sub-national levels from 2013- 14 onwards only on the website (as on December 5, 2021). Since 2008, MGNREGA covered the entire country with the exception of districts that had a hundred percent urban population. Yet, the MIS data for MGNREGA (https://bit.ly/3mszobX) is not available on the website from 2008 onwards. More importantly, a report on MGNREGA, edited by leading economist Dr. Mihir Shah (2012) had recommended national level studies to verify the authenticity of MIS data. However, the present author knows little about recent national level NSO surveys conducted to separately verify the authenticity of the MIS data.20

Data suppression during the Covid-19 pandemic

Various studies during the Covid-19 pandemic indicate how the official data (https://www.mygov.in/ covid-19/) suppressed the number of deaths in the country during the first and second waves.21 The official count of Covid-19 deaths is around 4 lakh. However, a study by Abhishek Anand from Harvard University, Justin Sandefur from the US-based think tank Center for Global Development, and India’s former chief economic adviser Arvind Subramanian (2021) has provided three different estimates of excess deaths due to the pandemic (during the period from April 2020 to June 2021). The extrapolation of state-level civil registration from seven states indicate 3.4 million excess deaths, whereas the application of international estimates of age-specific infection fatality rates (IFR) to the Indian seroprevalence data has found an excess mortality of about 4 million. Using the Consumer Pyramid Household Survey, a longitudinal panel of more than 800,000 individuals across all states, they estimated nearly 4.9 million excess deaths. According to the World Health Organization, excess mortality or excess deaths is defined as the difference in the total number of deaths in a crisis compared to those expected under normal conditions.22 The Covid-19 excess mortality accounts for both the total number of deaths directly attributed to the virus as well as the indirect impact, such as disruption to essential health services or travel disruptions. Besides Anand, Sandefur, and Subramanian (2021), various media organisations, independent data journalists, and research analysts came out with their own estimates to show that the official death toll did not reveal the reality. Rather, the government underreported (undercounted) Covid-19 mortality in India and across states/ UTs.23

The data on deaths of migrant and informal workers, who trudged back to their native places (i.e., places of origin) from various cities and towns after the announcement of the 2020 national lockdown was also not provided by the government, in response to questions by Parliamentarians. For instance, in his reply to a question asked by K Navaskani, Suresh Narayan Dhanorkar and Adoor Prakash, the Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Labour and Employment Santosh Kumar Gangwar said that the government did not maintain any data on the number of migrant workers who lost lives during their return to the hometown.24 On the other hand, the data generated by a group of number crunchers (and later used by CSOs and media commentators), based on media reports, indicate that at least 991 non-Covid deaths had taken place between March 19, 2020 and July 30, 2020.25 Out of 991 deaths, 224 deaths can be attributed to starvation and financial distress, while 209 migrant or informal workers died by accident, as they walked or migrated. It is to be noted that 142 were suicidal deaths due to fear of infection, loneliness, lack of freedom of movement and inability to go back home, while 96 deaths took place while travelling in shramik trains. The direness of the situation is also underscored by 49 deaths in quarantine centres, 47 deaths owing to exhaustion of walking or standing in queues and 80 for the lack of medical care or attention. Additionally, 12 deaths occurred due to police brutality or state violence.

Conclusion

All the listed examples of Section 4 of the RTI Act violations are just the tip of the iceberg. The real skeletons may tumble out of the cupboard when one starts auditing or assessing the proactive disclosure mechanisms followed by various state-level public bodies and local-level urban and rural bodies/ public authorities. Besides conducting third party auditing of proactive disclosure by public authorities, individuals, civil society organisations and private bodies too can pursue such auditing exercises on their own by following a scientific methodology created by experts. Survey of website users could also be undertaken to evaluate whether the websites are able to communicate to the citizens adequate information (as needed under the RTI Act) in a user-friendly manner.

End notes

- Right to Information Act, 2005

- Gandhi, Shailesh and Kachare, Pralhad (2016) RTI Act: Authentic Interpretation of the Statute. Vakils, Feffer & Simons Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved November 28, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3lh91Fi

- Tiwari, AN and Ansari, MM. Transparency Audit of Disclosures u/s 4 of the Right to Information Act by the Public Authorities. (2018, November) Central Information Commission. Retrieved November 30, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3rto5DO

- Upadhyaya, Himanshu. (2014, September 2). What good is an auditor without information? India Together. Retrieved November 23, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3EjIMWn

- Upadhyaya, Himanshu (2008, November 9). CAG conference: Caged tiger, much ado. India Together. Retrieved November 23, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3EmOy9x

- Reserve Bank of India. Bank Notes. Retrieved November 23, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3nZ9TjQ

- Bhardwaj, Anjali and Johri, Amrita. Right to know, right to live. A Primer on The Right to Information Act, 2005. (2016). Retrieved December 22, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3pieSwA

- Jebaraj, Priscilla (2021, January 11). No record of consultations on farm laws. The Hindu. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3d9jv56

- TNN (2021, January 13). RTI queries on debate on draft drew a blank. The Times of India. Retrieved December 1, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3lDogc6

- Banerjee, Abhijit V, et al. (2017, April 4). From being world leader in surveys, India is now facing a serious data problem, The Economic Times. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3E2D4Ih

- Jha, Somesh (2019, November 15). Consumer spend sees first fall in 4 decades on weak rural demand: NSO data. Business Standard. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/34YuOtx

- Household Consumer Expenditure Survey (2019, November 15). Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation. Retrieved November 28, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3ryOi3X

- Rangarajan, C and Dev, S Mahendra (2019, December 13). Mind the statistics gap, The Indian Express. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3Dsq9y2

- Seshadri, Suresh (2019, November 24). What is Consumer Expenditure Survey, and why was its 2017-2018 data withheld? The Hindu. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/32TJ6gR

- Sethi, Nitin (2014, December 24). Tribals worse off, facing alienation, says high-level panel report. Business Standard. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3I7hl4l

- Chakravarti, Sudeep (2015, January 23). The trouble with India’s tribals. Mint. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit. ly/3EjMoHV

- Patil, Mukta (2014, December 29). Report on India’s tribal population kept under wraps. Down to Earth. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3I7EmUJ

- Open Government Data (OGD) Platform, India. National Informatics Centre. Retrieved November 28, 2021 from https://bit. ly/3rwVQUF

- Patel, Vikram et al (2012, June 23). Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey. The Lancet. Vol. 379, Issue 9834, 2343–2351. Retrieved November 30, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3GdKQQ3

- Shah, Mihir. MGNREGA Sameeksha: An Anthology of Research Studies on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, 2006-2012 (2012). Ministry of Rural Development. Retrieved November 28, 2021 from https://bit. ly/2ZWqJqd

Also see, Ghatak, Shambhu (2013, June 12). MIS = Too many mistakes! India Together. Retrieved November 28, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3ElDlGp - Anand, Abhishek, Sandefur, Justin and Subramanian, Arvind (2021, July 20). Three New Estimates of India’s All-Cause Excess Mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Center for Global Development. Retrieved November 30, 2021 from https://bit. ly/3xZ460T and https://bit.ly/3lwYMNk

- World Health Organisation. The true death toll of COVID-19: Estimating global excess mortality. Retrieved November 21, 2021 from https://bit.ly/2ZWmlHV

- Chintan, Richa (2021, July 25). Several Studies Using Diverse Methods Point to Undercounting of COVID-19 Deaths, Govt in Denial. NewsClick. Retrieved November 25, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3lB8xdA

- Reply to the Unstarred Question no. 174 (to be answered on 14 September, 2020) asked by Shri K Navaskani, Shri Suresh Narayan Dhanorkar and Shri Adoor Prakash, and answered by the Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Labour and Employment Shri Santosh Kumar Gangwar, Lok Sabha. Retrieved November 21, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3EtYVZw

- Thejesh GN. Non-virus Deaths. Retrieved November 21, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3DqGnYs

Also see, SWAN. No Data, No Problem: Government of India in Denial about Migrant Worker Deaths and Distress in the Monsoon Session of Parliament. (2020, September 15) Retrieved November 21, 2021 from https://bit.ly/2ZYdXYo

NEXT »