The EV Ecosystem: Not so Revved Up?

An Update of India’s Electric Transport Policies

Susmita Saha*

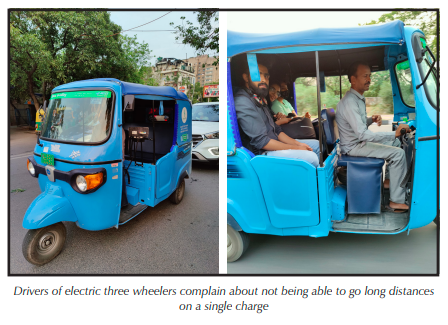

“Halat kharab ho rakkhi hai (We are in a dire predicament),” says Pal Singh, 48. Singh, a resident of Delhi’s Mahipalpur is an autorickshaw driver who occasionally plies his son’s electric three wheeler in Vasant Vihar.

When asked if the shiny, new electric vehicle has brought him new hope, his litany of woes begin. The biggest problem is the lack of enough charging stations, he says. Even after three hours of charging, the vehicle just manages to cover roughly 100 km. “What if I get a booking for Anand Vihar, how do you think I can say yes?” he wonders.

Few charging points also translate into long queues. While the charging service itself is free, most drivers have to first contend with the long charging time of vehicles in front of the queue. Their own turn to charge, again for a hefty duration, comes only after others before them are done. “Sometimes my son has to spend the entire night to charge his three wheeler, as there are many before him. And it’s not as if the rickshaw will go more than 100 km if charged for a longer span,” rues Singh, adding that there are fewer rides to take up when mounting costs of food and rented accommodation are already taking a toll.

Policy Implementation on Ground

Yes, change is in the air. Even if there are lots of teething troubles, our commute will be electric in the days to come.

Electric bus fleets have already hit the road and local governments are talking about sustainable public transport and making lifestyle changes on messaging apps. Even I received a Whatsapp invite from the Delhi government to try out their new e-buses that are pegged to be ‘zero pollution’ and ‘zero noise.’ For a metropolis, crowned as the world’s most polluted capital city for the fourth year in 2021, it was thrilling news.

But complete fleet electrification is still a long way off. Despite Delhi’s on-road vehicles making some headway in the green zone, transportation’s electric future continues to hang in the balance. The National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP) was launched by the Government of India, way back in 2013. The document offered an outline for the faster adoption of electric vehicles and their manufacturing in the country

Among its many objectives, enhancing the national fuel security, providing affordable and environmentally friendly transportation and enabling the Indian automotive industry to achieve global manufacturing leadership were key. Under the NEMMP 2020, there was also a target to achieve 6-7 million sales of hybrid and electric vehicles by the year 2020.1

Fuel security, as one of the defining goals of the plan, makes sense for India. Experts are firm that the faster acceptance of electric vehicles can significantly shrink the nation’s import reliance and contribute to its wallet size: “India depends on imports for approximately 85% of its domestic oil consumption, and spends a third of its total import values on crude oil alone. If electric vehicles occupy 30% share in new vehicle sales by 2030, India’s oil import bills could reduce by 15% by around INR 1.1 lakh crores in 2030 alone.”2

In addition, the country needs transportation that can double as a climate solution more than ever before. A 2020 Factsheet developed by the University of Chicago says that India is the world’s second most polluted country. Air pollution shortens the average Indian life expectancy by 5.2 years, relative to what it would be if the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline was met.3

Policymakers are hoping that accelerated electrification of transportation is the magic bullet to combat both pollution and the climate emergency. Energy itself is expected to get greener with fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), powered by hydrogen, which the country has already started manufacturing.

But right now, the nation’s green journey is both slow and at best, sputtering. Even in the Capital, both electric buses as well as other electric vehicles are few and far between. A few charging stations can be seen strewn across the main thoroughfares, although some of them are not functioning.

Experts are firm that the faster acceptance of electric vehicles can significantly shrink the nation’s import reliance and contribute to its wallet size

Occasionally stray cattle can be seen circling some of the empty and isolated charging points. With this kind of infrastructure, there haven’t been too many converts. According to recent research by Accelerated e-Mobility Revolution for India’s Transportation (e-amrit) portal in India, only 7,96,000 electric vehicles have been registered till December 2021, and only 1,800 charging stations have been installed in public places.4

Even auto driver Pal Singh concedes that the government needs to step on the gas to drive home its electric mobility ambitions: “The moment we picked up our EV, the EMIs have kicked in. No landlord will allow us to charge our vehicle at home. Till the time the government puts a proper infrastructure in place, we will continue to be miserable.”

Policies Offering a Green Roadmap

Despite an early push given by way of a bouquet of encouraging policies, more focus is needed. As part of the NEMMP 2020, the Department of Heavy Industry came out with

Policymakers are hoping that accelerated electrification of transportation is the magic bullet to combat both pollution and the climate emergency

the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles in India (FAME India) Scheme in 2015. The end goal? To promote manufacturing of electric and hybrid vehicle technology and to ensure its sustainable growth. However, the push to electrify transport on the ground left much to be desired in the early days.

As the Common Cause petition, filed in 2019, notes, there has been “Government’s failure to enact a suitable regime of incentives and disincentives to promote the adoption of ‘zero emission’ vehicles.”

The Common Cause petition explains why the FAME India scheme to implement NEMMP-2020, promulgated in 2015, fell woefully short: “Whereas NEMMP-2020 had envisioned that by 2020 India would adopt close to 7 million electric vehicles …, as of January, 2019, only 0.263 million electric vehicles have been adopted in India…”

Crucially, the implementation scheme lacked financial muscle. “Whereas NEMMP-2020 had called for an investment of about 14,500 crores from the government…the total funds allocated thus far were 579 crores as against a total outlay of 850 crores,” stated the petition.

The second edition of the FAME scheme had stronger feet to stand on. The Department of Heavy Industry notified Phase-II of the Scheme on March 8, 2019, with the approval of the Cabinet. It had an outlay of Rs. 10,000 crore for three years, starting from April 1, 2019. Fast-tracking local manufacturing and incentivising purchase of electric mobility were drivers of this plan.

Yet barriers to faster adoption of electric vehicles remain. Manufacturers have remained anxious about the slow uptick of sales and have even called for government interventions at the policy level to generate demand. In 2021, manufacturers called for urgent action ahead of the upcoming Union Budget. The Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV) even asked Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman to “either rejig the FAME II scheme or reintroduce FAME I, saying the programme meant to promote EVs in its second avatar has been able to achieve less than 10 per cent of its target.”5

The government, on its part, has announced measures aimed at encouraging EV purchases. During this year’s Union Budget, the Finance Minister revealed the government’s plan to come up with a battery swapping policy, targeted to decrease upfront EV price tags. On May 9, the Niti Aayog published the draft battery swapping policy for public consultation. The policy aims to support the faster adoption of EVs in the electric scooter and three-wheeler electric rickshaw segments as battery swapping is generally used in smaller vehicles with smaller battery packs. This becomes especially relevant, if policymakers want battery swapping to be the springboard to boost demand.

Unaffordability of electric vehicles, as compared to their polluting counterparts, have long remained a barrier for faster adoption, argue stakeholders. To that end, the draft battery swapping policy lists several proposals. Among many measures, it has prescribed “offering incentives to electric vehicles (EVs) with swappable batteries, subsidies to companies manufacturing swappable batteries, a new battery-as-aservice business model, and standards for interoperable batteries...”6

Also, it seems the government is eager to resolve the complaints of long charging downtime put forward by the likes of Pal Singh. Battery swapping, hoping to detach charging and battery usage, will go a long way in cutting down the charging downtime.

Manufacturers have remained anxious about the slow uptick of sales and have even called for government interventions at the policy level to generate demand

From safety standards to battery as a service, the draft policy attempts to cover most concerns. It has prescriptions for higher safety nets for end users, given that a host of electric bikes went up in flames across India recently Sensing that these widely publicised incidents could scare away potential buyers and put brakes on the country’s plans to electrify its transport fleet, the draft policy has specified stricter regulation for battery norms.

According to it, “The Policy will only support batteries using ‘Advanced Chemistry Cells’ (ACC), with performance that is equivalent or superior to EV batteries supported under the FAME-II scheme.”

Yet, the wheels-on-battery revolution isn’t really keeping pace with the global sprinters. Despite clocking an upswing in sales, the pace of green mobility in the country is slower than biggies like China and the US. By 2040, just 53% of new automobile sales in India will be electric, compared with 77% in China, according to research provider BloombergNEF.7

Hence, there’s an urgent need to catch up, given that we are already battling the twin scourges of high oil imports and climate change devastations. To smoothen the journey of buyers and encourage a faster switch, the draft policy also focusses on ensuring interoperability for the end-users, by asking for end-toend compatibility between batteries and other components of the swapping ecosystem.

Lately, the government has also approved the PLI (Production-Linked Incentive) scheme for the automobile and the drone industry, with a budgetary outlay of Rs 26,058 crore to incentivise electric vehicle (EV) and fuel cell EV manufacturing.8 Although aimed at improving local manufacturing capabilities and foster rapid production of environmentally cleaner vehicles, the scheme has generated a mixed response.

The scheme’s steep qualification criteria will keep away specialised Indian manufacturers of electric two and three wheelers, feel EV makers. An automaker must have a group-level revenue of at least `10,000 crore and have made a minimum investment of `3,000 crore in fixed assets to qualify for this scheme. Critics feel that the scheme is not inclusive enough as it will favour legacy players and will not be beneficial to start-ups in the pure-play two wheeler space.9

Despite the grievances, auto majors of every denomination have a skin in the game. From Goliaths like Tata Motors, Mahindra Electric Mobility and Hero Electric to newer brands, including Ather Energy, Okinawa and Simple Energy, everyone is now a part of India’s massive transport decarbonisation plan. The Union government, along with the states are helping them move in top gear. At least 15 Indian states have either approved or notified EV policies, with six more states in the draft stage. States like Delhi, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Meghalaya are focusing on demand incentives, whereas southern states and Uttar Pradesh are focusing on manufacturer-based incentives.10

Global Best Practices

One thing is for sure. The global transport domain is being redefined by electric vehicles and India is a market unlike any other. The Paris Agreement, which has given the world a shove to cut out greenhouse gas emissions, will just be a broken promise, if the much-polluting transport sector does not transform in a fast and meaningful way.

Unaffordability of electric vehicles, as compared to their polluting counterparts, have long remained a barrier for faster adoption, argue stakeholders

In addition, India has the potential to become a giant global manufacturing hub of EV components. That can only happen if the policy environment stays ahead of the global curve. We can follow in the footsteps of nations that are making big strides in electric mobility transition and learn from their best practices.

Following are the countries that have set targets and proposed strategies that accelerate mobility transition and offer tangible policy roadmaps to an EV-driven future. For many of these countries, the strategies are a clever mix of government financial incentives, infrastructure and technology development support, financial mechanisms and much else.

Norway: Norway has been among the big success stories of the clean mobility world. “Almost sixtyfive percent of new passenger cars sold in Norway in 2021 were electric; in addition, 22% were plugin hybrids. Put differently, only 14% of new cars were sold without a plug.”11 The purchase incentives provided by the country for EVs are strong as well. Also, Norway has been giving tax incentives from way back in 1990. According to the report ‘Best practices in electric mobility,’ by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Norway charges an import or registration tax for all cars which can reach about 10,000 Euros or more depending on the CO2 emissions. BEVs (Battery Electric Vehicle) are completely exempt from this tax. In addition, BEVs are exempt from paying 25 per cent VAT charged at the time of purchasing or when leasing an electric vehicle. Road tolls are mostly exempt for EVs in Norway. This exemption may be phased out, however it will still continue to be less than 50 per cent of the charge for ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) vehicles.12

China: Deployment of fast charging networks is also a key to building EV sales momentum. The above UNIDO report states that many stakeholders in China, including the government, local government and utilities, have been active in quickly building a fast DC charging infrastructure network in the country. What’s more, the fast charging infrastructure deployment resulted in huge electric vehicle uptake.

In 2017, China had around 83,000 publically accessible fast chargers and 130,000 publically accessible slow chargers. That same year, China had the largest electric car stock at 40 per cent of the global total, with an auto market share of 0.2 per cent. Electric cars sold in the Chinese market more than doubled the amount delivered in the United States, the second-largest electric car market globally.13

Japan: Public charging infrastructure has been taken seriously by Japan as well, as a means to promote electric vehicles as a sector.

In 2013, the government came up with the Japan Next Generation Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Deployment Promotion Project to offer financial back-up to charging stations around cities and highway rest stations in 2013 and 2014. The Development Bank of Japan tied up with Nissan, Toyota, Honda, Mitsubishi, and power company TEPCO to build the Nippon Charge Service (NCS), a nationwide network of charging stations, now operated as a private joint venture.14

European Union: Accelerating local manufacturing lay at the heart of India’s policy frameworks around EVs. However, some manufacturers feel that the sluggish deployment pace of EVs in the country can be attributed to slower evolution of the domestic component manufacturing market. 15

On the other hand, regions like the European Union are stepping up efforts to build a strong battery industry. An International Energy Agency (IEA) report says that there’s something called the European Battery Alliance to promote local competitive and innovative manufacturing.

In early 2021 the European Commission had a funding package of EUR 2.9 billion to strengthen the spine of a pan-European research and innovation project, in the context of the entire battery value chain. Labelled the European Battery Innovation, the project will be bolstering 12 countries through 2028. “Poland is positioning itself as a central EV manufacturing hub for Europe: in early 2020 the European Investment Bank supported the construction of a LG Chem Li-ion battery cells-to-packs manufacturing gigafactory in Poland.”16

New Zealand: Legislation to enforce stringent regulations on vehicle emissions is an important factor to fast-track transport electrification. The IEA report ‘Global EV Outlook 2021,’ also speaks of partnerships forged between the New Zealand government and private sector to greenlight low emissions transport projects. In 2020, the government and the private sector co-financed 45 new low-emissions transport projects, including charging infrastructure and BEV trucks.17

There’s also a February 2021 draft advice package from New Zealand’s Climate Change Commission that recommends a number of policies to accelerate the uptake of electric LDV (Light Duty Vehicle)s, including banning the import, manufacturing or assembling of light-duty ICE vehicles from 2030.18

Conclusion

The volumes of green vehicles being put out on the world’s busiest thoroughfares are surpassing expectations every day. The sale of electric cars (including fully electric and plug-in hybrids) increased twofold in 2021 to 6.6 million, with more now sold each week than in the whole of 2012, according to the latest edition of the annual Global Electric Vehicle Outlook. The number of electric cars on the world’s roads by the end of 2021 was about 16.5 million, triple the amount in 2018.19 There is no doubt that the green transport transition is both real and imminent. But it is also true that it will take place at different speeds across advanced and developing economies.

A lot of factors can contribute to an even faster transport decarbonisation, including continued policy support, efforts to reduce the lifetime costs of owning an EV, serious decline in battery costs that lead to higher upfront costs of vehicles and much more. In fact, India could do way better in this transportation revolution if it also includes trucks in the policy spotlight and incentive reinforcement ambit currently offered to two and three wheelers, cars and buses. The country boasts of more than 2.8 million trucks plying over 100 billion km per year. They may constitute about 2% on-road vehicles, but these heavy-duty vehicles contribute about 40% of emissions and fuel consumption from road transport. Electrification of trucks through fiscal incentives, regulatory targets on emissions, innovative business models and public-private partnerships could change the game in favour of clean transportation.20

One thing needs to be absolutely clear. India cannot afford to ignore the nightmares of climate change, including wildfires, heatwaves, floods and cyclones any longer. Creating new capabilities in the EV sector, boosting fuel security and reducing fossil fuel imports, while looking at this world-wide transport transition as an opportunity, is the only way to win this race.

Image Courtesy: Susmita Saha and Divyanshoo Singh

* Susmita Saha is Senior Research Analyst at Common Cause

(Endnotes)

- (1) Ministry of Heavy Industries & Public Enterprises. (2019, July 8). Implementation of National Electric Mobility Mission Plan. Press Information Bureau. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3tHNYA7

- (2) Ghosh, U. (2022, March 22). Soaring oil prices may fuel EV sales, save oil imports worth INR 1 lakh crore for India by 2030. ETAuto.com. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3mY8EjA

- (3) Air Quality Index-Fact Sheet. EPIC-India. (2020). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3tLYxBY

- (4) Khan, I., & Mehta, Y. (2022, February 18). How Can India Ensure a Higher EV Adoption Rate. Inc42. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3y6x94y

- (5) PTI. (2021, January 25). Budget 2021: Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles calls for rejig of FAME II. The New Indian Express. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3QusoZA

- (6) Barik, S. (2022, April 21). Explained: What are the key proposals in Niti Aayog’s draft battery swapping policy? The Indian Express. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3xBGgc0

- (7) Saxena, R. (2022, April 5). India’s EV Sales Seen Doubling Led by Battery-Powered Scooters. Bloomberg.com. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bloom.bg/3N4A2ai

- (8) Sorabjee, H. (2021, September 15). PLI scheme for auto sector gets green signal, big gains for EVs and FCEVs. Autocar Professional. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3n30Fli

- (9) Barik, S. (2021, September 20). India’s Rs 26000 Cr PLI Scheme for auto manufacturing cuts out EV startups. Entrackr. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3O5BdHO

- (10) PTI. (2021, December 16). Electric vehicle mkt to see investment of Rs 94000 cr in next 5 years: Report. The Economic Times. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3O5BdHO

- (11) Bu, C. (2022, January 7). Lessons From Norway About How to Switch to Electric Vehicles. Time. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/39EXwoI

- (12) Best Practices in Electric Mobility. United Nations Industrial Development Organization (2020). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3zLyP4F

- (13) Best Practices in Electric Mobility. United Nations Industrial Development Organization (2020). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3zLyP4F

- (14) Emerging best practices for electric vehicle charging infrastructure. International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). (2017). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3zPyvSv

- (15) Moerenhout, T. (2021, July 28). Is India Ready for an Electric Vehicle Revolution? International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3zSXtAf

- (16) Global EV Outlook 2021: Accelerating ambitions despite the pandemic. IEA. (2021). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3xKRjQ6

- (17) Global EV Outlook 2021: Accelerating ambitions despite the pandemic. IEA. (2021). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3xKRjQ6

- (18) Global EV Outlook 2021: Accelerating ambitions despite the pandemic. IEA. (2021). Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3xKRjQ6

- (19) Press Release (2022, May 23). Global electric car sales have continued their strong growth in 2022 after breaking records last year. IEA. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3y52ZhU

- (20) Bhatt, A., & Yadav, A. (2022, May 21). Where Are India’s Electric Trucks? The Wire. Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://bit.ly/3tNjcWl

NEXT »