How to Balance Clashing Rights?

CONSTITUTION & THE RULE OF LAW

How to Balance Clashing Rights?

Radhika Jha*

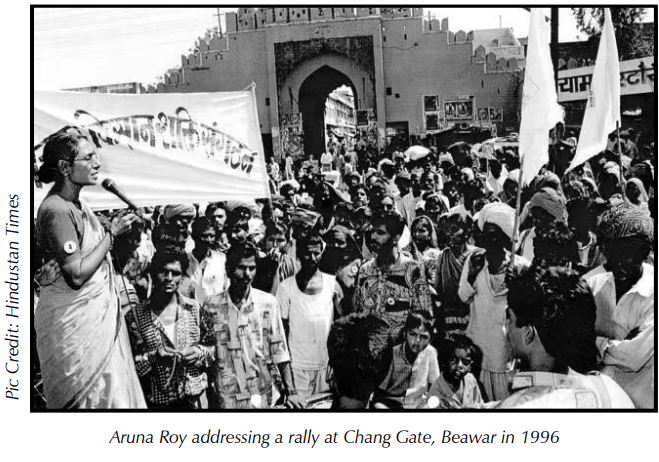

In the 1990s, jansunwais, or public hearings were organised by the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) in the villages of Ajmer districts of Rajasthan.

Two sarpanches were held accountable for corruption and had to return the misappropriated amounts to the Panchayat funds during the jansunwai. Consequently, the District Collector ordered a special audit and ensured the recovery of money, while police complaints were filed against the sarpanches and they were arrested.1 These jansunwais, along with a series of similar public hearings, dharnas and public movements originating in Rajasthan, led to the formulation of the law on Right to Information in India.

Now consider this:

In Hyderabad, during the national lockdown following the Covid-19 pandemic, activist SQ Masood was stopped by the police in the street, asked to remove his mask, and had his photo taken by the police. This photo, taken without his consent and without any cause for suspicion, was used to create the database for Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) to be used by the police.2 Aside from raising many privacy concerns, this practise is also deeply flawed because of the inherent limitations of the technology, which suffers from notable levels of misidentifications and inaccuracies, as has ironically been revealed through RTI applications3 .

Even though these two cases are set apart not just by several decades and by geography, but also by the nature of the cases themselves, there are some common larger questions that these cases raise: how much and what information needs to be public, and what should remain private? Who has the right to obtain such information and for what purposes?

In the first case, if the Rajasthan villagers were told that the information they were seeking regarding the use of Panchayat funds could not be shared with them because it included personal information of the people/contractors involved in the transactions, would they have been able to unearth the details of the misappropriation and have the amount reimbursed? On the other hand, in the absence of any protection for the right to privacy how would SQ Masood and many others (including those who, like him, are likely to be on the radar of the police because of their religious or other socioeconomic identity) safeguard their own personal, identifiable information against the state, as well as private actors who may use it without their consent?

There are no easy answers to these questions. These questions bring out the core tension between two seemingly opposing rights—the right to privacy and the right to information.

The government knows everything about us, but what do we know about it?

Hierarchy of Rights

In this article, we try to address these questions by looking at how the Indian state has balanced other opposing rights and what are the prevailing legal philosophies that apply in the determination of these hierarchy of rights. Which rights take precedence over others, and why?

It is also important to analyse whether Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act, which significantly weakens the Right to Information Act through an amendment, will address this apparent conflict between the two rights, or if there even is a conflict to begin with? Can these two rights be, in fact, complimentary to each other?

We conclude the article by arguing that the conflict between these two rights is in fact artificial to a large extent. The exception for “larger public interest” is inherent in the right to privacy. This has also been recognised in a Supreme Court verdict upholding Aadhaar.

In this artificially created clash of rights that Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act seeks to resolve, the citizens will end up with nothing, without the full realisation of either of these rights. It is also important to note that the right to information seeks data from the government, while the DPDP Act opens a wide scope for the government to collect and use people’s personal data, whether it is for reasons of national security, public order or prevention and investigation of offences—terms which are abstract and prone to misuse. The government, thus, knows everything about us, but what do we know about it?

Theories for Resolving Conflict of Rights

Pratap (2022) broadly categorises rights adjudication in two models—the rights ‘specification’ model and the ‘balancing’ model. In the rights specification model, some rights are accorded special moral, political and philosophical status and they ‘trump’ all other rights. In the case of a conflict, these rights prevail. This model is largely followed by the constitutional courts in the United States. On the other hand, in the balancing model, the contents and boundaries of the rights are stated generally and broadly, and these rights are balanced by the courts. The conflicting rights are weighed against each other to decide which one prevails in a specific context. The most widely accepted principle of this model is the ‘proportionality’ doctrine where courts consider whether a particular measure affects a right, and if the interference in the right is justified.

To ascertain whether an interference is justified, the court considers the following:4

- Legitimate aim: If there is a ‘sufficiently important’ aim for the interference of the right.

- Rational nexus: If the interfering measure is rationally connected to the legitimate aim.

- Necessity: If the measure affects the right only to the extent necessary.

- Proportionality stricto sensu: If the effects of the measures are proportionate to the objective of measures i.e., the benefits of infringement of the right must be greater than the loss incurred concerning the protected right or interest.

Pratap argues that Indian courts fail to structure its reasoning according to these models. Courts rarely contextualised the conflict of rights down to the facts of the case.5

Bhatia (2020) calls the balancing of rights the “anti-exclusion principle”. Recognising that the Constitution guarantees rights to both individuals and groups, he argues that in cases of conflict, the balancing of rights is essential. This can be done by “asking whether a particular practice under consideration has the effect of causing exclusion, or of treating certain constituents as second-class members of society, in ways that harm their dignity, or other rights in the non-religious domain.”6

We look at a few cases of conflicting rights that have come up before the Indian Supreme Court.

Individual’s Right to Worship vs. Community’s Right to Religious Practise: The Sabarimala Verdict

One of the recent cases that caught public attention and brought out polarising opinions was the Sabarimala Temple case, where the temple’s practise of barring entry to menstruating women (women between the ages of 10 and 50), was questioned and ultimately held to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

In 2018, the Supreme Court delivered this landmark judgment in the Indian Young Lawyers Association v. State of Kerala case, holding by a 4:1 majority that women’s entry to the temple cannot be barred. The case juxtaposed the community’s right to religious practice and tradition against the constitutional principles of equality, non-discrimination, and the right to religious freedom. In effect, the Court was asked to navigate a complex web of statutory law, religious doctrine, and constitutional guarantees, to determine whether a religious practice rooted in custom could stand the scrutiny of the Constitution.7

Renowned constitutional law scholar Gautam Bhatia analysed the Sabarimala judgement from the perspective of group autonomy and cultural dissent.8 Borrowed from Madhavi Sundar, the term “cultural dissent” refers to norms and values defined and imposed by cultural gatekeepers and dominant groups, which have been challenged. Both Justice Chandrachud and Justice Nariman recognise that cultural dissent is at the heart of the Sabarimala issue.

Bhatia argues that when marginalised groups within cultures or religions challenge oppressive norms or practices, more often than not, they will need an external authority (such as Courts, acting under the Constitution) to support them in that struggle. However, the claim must originate from the marginalised groups themselves. An external authority cannot assume the mantle of speaking on their behalf.

On the other hand, in her dissenting opinion, Justice Indu Malhotra upholds the principles of group autonomy over individual rights. She argues that the exclusion of women is an “essential religious practice” and therefore protected by Article 25(1). She further notes that constitutional morality in India’s plural society requires respect and tolerance for different faiths and beliefs, which have their own sets of practices that might nevertheless appear immoral or irrational to outsiders. Thus, she was of the opinion that discrimination against women is in fact not counter to constitutional morality

However, the majority decision taken by the Court gives precedence to individual rights over group autonomy. In choosing to privilege the former, the majority signalled a decisive shift in Indian constitutional jurisprudence: from preservation of custom to a vision of transformative justice anchored in dignity and equality.

In another context, Gautam Bhatia argues that the Indian Constitution is committed to an ‘anti-exclusion principle’– that is, group rights and group integrity are guaranteed to the extent, and only to the extent, that religious groups do not block individuals’ access to the basic public goods required to sustain a dignified life.9

In the balancing model, the conflicting rights are weighed against each other to decide which one prevails in a specific context

Right to Enjoy Property vs. The Right to Protest

In the case of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) vs. Union of India, 2018, decided just a few months prior to the Sabarimala judgement, the petitioner argued that though a particular order passed under Section 144 of the CrPC remains in force for a period of 60 days. On the expiry of the said period another order of identical nature is passed, thereby banning the holding of public meetings, peaceful assembly and peaceful demonstrations by the public at large. This, according to the petitioner, is the arbitrary exercise of power which infringes the fundamental right to peaceful assembly guaranteed under Article 19(1)(b) of the Constitution of India. By these orders, the entire Central Delhi area is virtually declared a prohibited area for holding public meetings and dharnas or peaceful protests.

In this case, the Court held that “no fundamental right is absolute and it can have limitations in certain circumstances. Thus, permissible limitations are imposed by the State. The said limitations are to be within the bounds of law.”10 When it comes to intra-conflict of a right conferred under the same article, the test applied should be that of “paramount collective interest” or “sustenance of public confidence in the justice dispensation system”, as per the judgement. The Court gave the example of the Vikas Yadav vs State of UP11 case wherein it was held that a group of persons, in the name of “class honour”, cannot curtail or throttle the choice of a woman.

The Court further said that the test of primacy of rights, which is based on legitimacy and public interest, has to be adjudged on the facts of each case and cannot be stated in abstract terms. It upheld the need for balancing of rights, by ensuring that that one right is not totally extinguished over the other.

It held that “Balancing would mean curtailing one right of one class to some extent so that the right of the other class is also protected.” In this case, however, the Court did not agree that the rights of the petitioner were being extinguished, since Section 144 contains a provision for permission that can be granted in some cases. It directed the Commissioner of Police and other official respondents to frame proper guidelines for regulating such protests, demonstrations, etc.

In essence, while the Court upheld the basic right to assembly and peaceful protest, it also held that the order to impose Section 144 was not unconstitutional and the protests should be regulated to ensure that the residents of that locality are not inconvenienced.

A similar issue was brought before the Apex Court in 2020, two years after the MKSS verdict, in the Amit Sahni vs Commissioner of Police case12. Following large-scale protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, a writ petition was filed by lawyer-activist Amit Sahni against the protests, saying that the public roads are obstructed by crowd protesting in the Shaheen Bagh locality. This was causing grave inconvenience to the commuters, the petitioner argued. Here too, while the Court recognised the right to freedom of speech and expression and the right to peaceful protests, it held that public ways and public spaces cannot be occupied for an infinite time period. It stated that while dissent and democracy go hand-in-hand, demonstrations expressing dissent must occur in designated areas.13

The Puttaswamy Judgements: Reasonable Restrictions to the Right to Privacy

In the landmark case of KS Puttaswamy vs Union of India, 2017,14 the Supreme Court held that the right to privacy is a fundamental right. The court held that the right to privacy “is a right which protects the inner sphere of the individual from interference from both State and non-State actors and allows the individuals to make autonomous life choices.” The court further said, “Statutory provisions that deal with aspects of privacy would continue to be tested on the ground that they would violate the fundamental right to privacy, and would not be struck down, if it is found on a balancing test that the social or public interest and the reasonableness of the restrictions would outweigh the particular aspect of privacy claimed.”

In the Sabrimala verdict the majority decision taken by the Court gives precedence to individual rights over group autonomy

Even as the judgement did not define the contours of the right to privacy (some of it was defined in what is known as the Puttaswamy II judgement of 2018, or the Aadhaar case), it is clear that even in the original verdict the court recognises the inherent reasonable restriction within the right to privacy in larger public interest.

In the 2018 Puttaswamy II judgement15, the court applied the proportionality doctrine to balance competing rights. In this, popularly known as the Aadhaar case, the collection and use of biometric data for Aadhaar and making it mandatory for accessing state subsidies were challenged. At the balancing stage, it principally prioritised the right to food, which was a part of the right to life, and upheld a substantial part of the program.

While subjecting the measure to the test of proportionality, Justice Sikri, in his majority judgement, considered the following:

- “the action must be sanctioned by law;

- the proposed action must be necessary in a democratic society for a legitimate aim;

- the extent of such interference must be proportionate to the need for such interference;

- there must be procedural guarantees against abuse of such interference”.

Justice Sikri laid down a four-fold test to determine proportionality:

- A measure restricting a right must have a legitimate goal (legitimate goal stage).

- It must be a suitable means of furthering this goal (suitability or rationale connection stage).

- There must not be any less restrictive but equally effective alternative (necessity stage).

- The measure must not have a disproportionate impact on the right holder (balancing stage).

Using this proportionality test, the majority opinion upheld this linkage with Aadhaar, with some provisions being struck down.

Justice Chandrachud, in his dissenting opinion, came to a different conclusion. He was of the opinion that just the legitimate aim is insufficient and it is important to meet other parameters of the proportionality test, and that the Aadhaar scheme has a disproportionate impact on the right holder.16

Conclusion

While these legal philosophies help in understanding various kinds of approaches that Indian courts take towards resolving the conflicts arising between different rights--or sometimes, within a right itself, a larger reading of different cases shows that there has been an attempt to align the existing rights with larger public interests. Even in the Puttaswamy judgement that held the right to privacy as a fundamental right, the court recognised and noted the inherent limitations within the right in larger public interest. It is thus ironical that the “public interest” provision from the Right to Information Act is being purportedly amended in the interest of the right to privacy.

The Courts have been inclined to give precedence to individual rights over group rights in case of an infringement of one by the other. However, this is a false dichotomy in the present case, seeing as how both right to information as well as right to privacy can be interpreted as individual rights that are, at times, accessed collectively. News reports are replete with cases of the right to information being used by individuals to access some of their basic rights. Thus, the larger “public interest” provision in the RTI Act in fact boils down to concrete access to essential rights such as the right to food, right to livelihood, right to education, right to life, freedom of speech, to name a few. Just as the government needs data on its citizens to provide services, the people also need access to the government data to hold it accountable and assert their basic rights. The Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act appears to be more of an attempt to systematically dismantle the right to information, rather than safeguard people’s right to privacy

References

- Mander, H. & Joshi, A. (n.d.). The Movement for Right to Information in India: People’s Power for the Control of Corruption. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/40GObUE

- Al Jazeera (20th January 2022). Facal recognition taken to court in India’s surveillance hotspot. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/46RA8Qb

- Jain, A. (17th August 2022). Delhi Police’s claims that FRT is accurate with a 80% match are 100% scary. Internet Freedom Foundation. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/4fdIovV

- Pratap, N. (2022), “Conflicting Fundamental Rights Under the Indian Constitution: Analyzing the Supreme Court’s Doctrinal Gap”. LL.M. Essays & Theses. 7. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3HajLU3

- Ibid.

- Bhatia, G. (16th February 2020). Nine Judges, Seven Questions. Constitutional Law and Philosophy. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3U107gj

- Bhatia, G. (28th September 2018). The Sabarimala Judgement – I: An Overview. Constitutional Law and Philosophy. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/4mjY0jN

- Bhati, G. (29th September 2018). The Sabarimala Judgement – II: Justice Malhotra, Group Autonomy and Cultural Dissent. Constitutional Law and Philosophy. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/45qCZhz

- Bhatia, G. (3rd November 2016). Freedom from community: Individual rights, group life, state authority and religious freedom under the Indian Constitution. Global Constitutionalism. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/41iT9XM

- Para 61, MKSS vs Union of India AIR 2018 SC 3476

- AIR 2016 SUPREME COURT 4614

- AIR 2020 SUPREME COURT 4704

- Suniksha, V.A. (n.d.). Case Comment: Amit Sahni vs Commissioner of Police & Ors. The Amikus Qriae. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/478UrbJ

- AIR 2017 SUPREME COURT 4161

- K.S Puttaswamy v. Union of India, (2019) 1 SCC 1 (India)

- A.K., A. (26th September 2018). Proportionality Test for Aadhaar: the Supreme Court’s Two Approaches. Bar and Bench. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/4l10nqw

NEXT »