India’s RTI Act in Global Perspective

SHADOWS IN THE MIRROR

India’s Transparency in Global Perspective

Rishikesh Kumar*

How much money was spent on the ‘Make in India’ project?

Not in the public’s interest. Denied.

How much money did the government spend on defence equipment last year?

Access denied—citing national security, individual privacy, or... no reason at all.

How many beneficiaries received subsidies under a flagship scheme?

Data not available in this format.

Why was my RTI request rejected?

Because we can.

Sounds strange, doesn’t it? Almost like fiction. But this is the future we’re inching toward—where your right to ask exists, but the right to get an answer quietly disappears.

Whether you’re a student curious about exam patterns, a journalist chasing a lead, a farmer asking where the subsidy money went, or just a citizen doing your duty—you could be denied answers. Legally.

Now you might think: Wait, how is that possible? RTI is still there, right? There’s been no amendment to it…

And you’re right. There’s been no direct attack on the Right to Information Act, 2005. No big headlines. No Parliament debate.

But here’s the twist: the blow didn’t come from the front—it came from the side. It’s strategic, subtle, and disguised under the sophisticated brand new law that claims to protect your personal data. Enter the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023—a law that says it’s here to protect your privacy. Sounds good, right? In today’s digital world, who doesn’t want their data to be safe?

But here’s the catch: While protecting your privacy, it quietly weakens your right to know. Buried in this new law is Section 44, which says that if any other law—including the RTI Act—goes against DPDP, then DPDP will take over. And that’s a problem. Because under the RTI Act, Section 8(1)(j) allowed access to personal information if it serves public interest—like exposing corruption or holding officials accountable. Now, that door is closing.

Under DPDP Act, if someone says, “its personal data,” that’s enough. No questions asked. No public interest test. No accountability.

So, while the RTI Act still exists, it’s being quietly sidelined—not by changing it directly, but by making it weaker through another law; a law that was supposed to protect your rights, but might end up protecting secrets instead.

The Irony of Amrit Kaal: Progress Without Permission to Ask

“How the UK Can Learn from India’s Right to Information Act” — The Guardian, 2010 “India’s Act is more powerful than its counterpart in the UK, particularly in its use of penalties for delay or non-compliance... The UK act gives officials a host of reasons to refuse information; this was strongly and successfully opposed by citizens in India.”

That was not from an Indian newspaper. That was The Guardian, writing from London—13 years ago. They were telling their government to look east, to India. To learn from a country that had just enacted one of the world’s strongest information laws. A country where ordinary citizens could demand answers and government officials could be fined—personally—for denying or delaying the truth.

Today, we are told that we’ve entered the Amrit Kaal—India’s golden era. An age of transformation. A nation leading on the world stage. We are the fourth-largest economy, set to overtake Japan in GDP, racing ahead with digital power, economic ambitions, and global influence.

But here’s the question no one wants to ask:

Are we entering this golden age with our mouths shut and our hands tied?

You can cheer for the growth, nod during the broadcasts, and repeat the national slogans. But try asking a tough question—Where did the money go? Who signed the contract? Why was that decision made?—and you might just hit a wall of silence. A legal silence, one that looks official, feels polite, but shuts the door just the same.

But let’s pause for a moment and go back—back to the time when India was not a rising power, but a newborn democracy, just stepping out of colonial rule. When our leaders sat down in the Constituent Assembly, they didn’t just write a Constitution—they studied the world. They read every major democratic constitution then in existence: the American Bill of Rights, the British parliamentary system, French civil liberties, Canadian federalism, Irish directives, and more. They weren’t trying to copy the West. They were trying to create something that worked for India—a democracy rooted in equality, justice, and above all, accountability.

The idea was simple but powerful: learn from the world, choose what works best, and make it our own. That’s how we got the Constitution we proudly celebrate today—a living document that gave citizens the right to speak, to ask, to challenge, and to know.

And now, as we face a new kind of threat—not from invaders or colonizers, but from within the framework of our own laws—the time has come to look outward again. Because as a nation, we have long believed in ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’—the world is one family. We’ve shown the world that learning from others is not weakness; it’s wisdom.

Always leading from the front is not the only mark of a true leader. Sometimes, being in the back—by listening, adapting, and evolving—is just as powerful.

So once again, let’s look beyond our borders. Not to borrow blindly. But to see how other democracies—many of which once looked up to our RTI law—are balancing the delicate line between personal privacy and public transparency. To understand how they’re protecting their citizens without silencing them. To ask: Are we truly protecting our people, or are we just protecting power?

International Comparison and Historical Context

The global evolution of Right to Information (RTI) laws can be traced back to Sweden, which in 1766 became the first country to adopt such legislation, driven by parliamentary efforts to ensure transparency in royal governance. This pioneering move laid the groundwork for future legislative developments in other democracies. A significant milestone followed two centuries later when the United States introduced its first Freedom of Information (FOI) law in 1966. Norway adopted a similar framework in 1970, signalling a gradual but steady trend toward institutionalising access to information.

While the RTI Act still exists, it’s being quietly sidelined—not by changing it directly, but by making it weaker through another law; a law that was supposed to protect your rights, but might end up protecting secrets instead

The momentum spread to other Western democracies, with France and the Netherlands adopting FOI laws in 1978, followed by Australia, New Zealand, and Canada in 1982, Denmark in 1985, Greece in 1986, Austria in 1987, and Italy in 1990. By the end of that decade, 13 countries had established formal RTI frameworks.

A pivotal moment came in 2000 with the adoption of the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, which explicitly enshrined both freedom of expression and the right of access to documents, thus reinforcing RTI as a core democratic value within the EU and setting a standard for other regions to follow.

Adopting a law is only the first step. What really matters is how deeply a country commits to upholding that law, strengthening it over time, and ensuring that citizens—not just institutions—remain at the heart of the process.

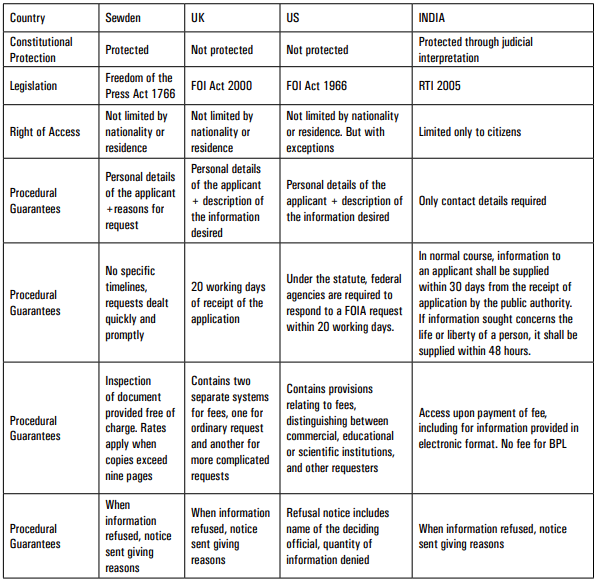

So, to see where we stand today, we’ve created a simple comparative table—looking at the Swedish, UK, US, and Indian access to information laws. We’ve compared how easy it is to file a request, whether the right is constitutionally protected, how exceptions are handled, and what penalties exist for noncompliance.

And we’ll leave it to you to decide: which one truly empowers its citizens—and which ones just pretend to?

But before you draw conclusions, here’s a bit of truth that stings.

According to a Times of India report from 2018, India was once a global leader in the right to information. When global RTI ratings began in 2011—measuring over 60 indicators like access, scope, appeals, and protections—India ranked number 2 out of 123 countries.

By 2018, we had slipped to number 6. Not a free fall, but still several steps down. And that was before the first major amendment hit RTI in 2019. Before laws like the DPDP Act, 2023, began quietly changing the rules of the game.

We are living in an age where truth no longer hides in locked cabinets—it floats in the cloud. In the era of artificial intelligence, block chain, cloud computing, and biometric surveillance, data has become currency. Every click, scroll, purchase, and post is recorded, processed, and often sold. The world has entered a digital economy where data is not just information, it is power. It drives markets, personalises services, predicts behaviour, and silently shapes choices.

But power, without checks, breeds risk.

The increasing commodification of personal data has exposed individuals to new vulnerabilities—identity theft, unauthorised profiling, digital surveillance. That’s why the need for robust data governance is not just technical, it’s constitutional. A democracy must strike a delicate balance: protecting privacy, ensuring data security, while never compromising the citizen’s right to transparency.

This article has attempted to explore that balance—not in theory, but in law.

The increasing commodification of personal data has exposed individuals to new vulnerabilities— identity theft, unauthorised profiling, digital surveillance. That’s why the need for robust data governance is not just technical, it’s constitutional

Global Overviews on Right to Information Laws

We compared India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 with the European Union’s GDPR—a gold standard for data rights. We saw how GDPR limits state surveillance, requires proportionality tests, grants individuals the right to object, and enforces strict penalties for breaches. By contrast, the DPDP Act offers broad government exemptions, lacks independent oversight, and weakens citizen control over personal data.

But this isn’t just a debate about privacy. It’s about something deeper: democratic accountability.

Because when the DPDP Act’s Section 44(3) overrides Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act, it doesn’t just secure personal data—it shields public offices from public questions. It tells the citizen, you have the right to be protected, but not the right to know. And in doing so, it hollows out one of the most powerful tools Indian democracy ever gave its people.

The Right to Information Act, 2005, especially Section 8(1)(j), provides the balance—protecting privacy unless a larger public interest demands disclosure.

According to Section 8(1)(j) in The Right to Information Act, 2005:

(j) information which relates to personal information the disclosure of which has no relationship to any public activity or interest, or which would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual unless the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the appellate authority, as the case may be, is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information

When the DPDP Act’s Section 44(3) overrides Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act, it doesn’t just secure personal data— it shields public offices from public questions

To insert Section 44(3) into this equation is not reform. It is retreat. In this new digital dawn, we need stronger rights—not quieter citizens. Let’s not dim the light of transparency just as the world gets more complex. Because in a democracy, data can be encrypted—but truth should never be.

A Final Thought: Different Questions, Same Silence

“Voter list? Will not give machine-readable format. CCTV footage? Hidden by changing the law. Election photos and videos? Now they will be deleted in 45 days, not 1 year. The one who was supposed to provide answers – is the one deleting the evidence.”

These words come from a member of the opposition—not directly linked to this article, but the reasoning behind them sounds all too familiar.

Yes, the subject is different. But the message is the same: Information is being taken away. The light is being dimmed. And the citizen is being left to guess. So, we ask again:

If Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act, 2005 already strikes a balance between privacy and public interest, then why introduce Section 44(3) of the DPDP Act?

Why create a law that overrides a hard-won right? Why weaken the very tool that has empowered so many to expose injustice, ask difficult questions, and demand answers?

At Common Cause, we have always stood for transparency, for privacy, for national security, and most importantly, for the constitutional rights of every Indian. But we have also stood—without compromise— against any move that chips away at public trust, that hides the state behind legal smoke, or that makes the people of India less powerful in their own democracy.

Whether the issue is election transparency, new criminal laws, police accountability, or digital surveillance—we believe that the right to information is not just a governance issue. It is linked to the Right to Life with Dignity under Article 21 of our Constitution. Because dignity begins with awareness. And dignity dies in silence.

So, we leave you with this:

Think about what is being taken away, and why?

Ask why questions are being treated like threats?

Write back to us. Join hands with us. And stand with the right to know

Because in the end, democracy is not built on announcements.

It is built on answers.

NEXT »