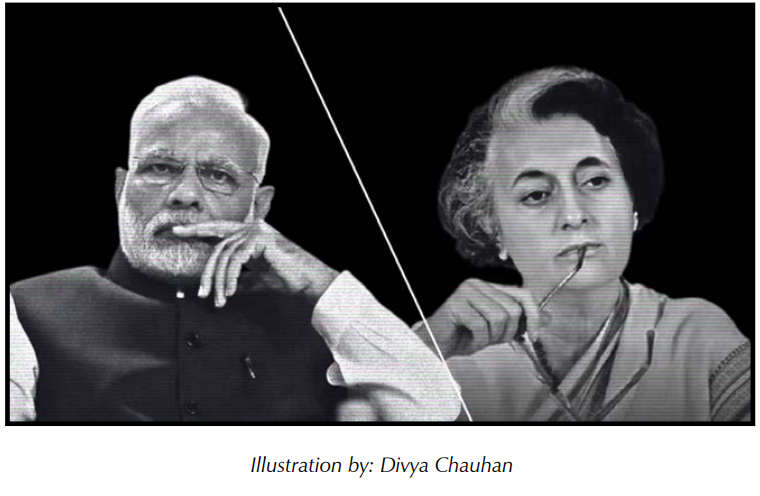

Ghosts of the Emergency

Is History Repeating Itself?

Divya Singh Chauhan *

In June 1975, Indira Gandhi dragged the nation into darkness. The judiciary had called her guilty of electoral malpractice. Instead of stepping aside, she suspended the Constitution itself and declared a state of National Emergency. Civil liberties were torn apart, opposition leaders locked away, and the press gagged until it crawled on its knees. For 21 months, the democratic apparatus was dismantled bit by bit by her government.

The Emergency lasted until March 1977 and remains one of the most egregious episodes in independent India’s constitutional history. When elections were finally held in March 1977, voters delivered a stunning verdict. Indira Gandhi was defeated, and democracy gasped for a breath again. However, the spirit of 1975 still roams, shape-shifting into new guises, seeking to haunt the democracy in more sophisticated and corrosive ways.

This article revisits the 1975 Emergency, attempting to trace its enduring imprint on the Indian order, and draw parallels with the democratic backsliding visible under the Modi government.

Blueprint for Authoritarianism

The Emergency left behind a dangerous blueprint for an authoritarian regime. It paralysed and dismantled every institution that guarded the Republic. These authoritarian tools of 1975--detentions, censorship, intimidation of unions and opposition--form the very skeleton of what an “Emergency” looks like. They serve as the template against which present-day practices can be measured.

Newspapers were forced into censorship, and journalists were jailed. Preventive detention became the government’s most powerful weapon. Indira Gandhi detained opposition leaders without trial under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) and the Defence of India Act and Defence of India Rules, 1962 (DISIR), which granted the state the authority to hold individuals indefinitely. According to the Shah Commission of Inquiry’s 3rd Final Report (1978), 34,988 people were arrested under MISA, and 75,818 people were detained under DISIR, including political leaders, activists, and trade unionists.

Jayaprakash Narayan, who led the movement for restoration of democracy, was imprisoned. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, LK Advani, Morarji Desai, and Charan Singh also spent months behind bars. Indira Gandhi obliterated the opposition in one swift stroke by incarcerating its leaders. Parliament became an extension of the Prime Minister’s will, with little room for debate or scrutiny.

Trade unions were among the first casualties of the Emergency. Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi saw them as threats to discipline. In June 1975, detention orders under the MISA were issued against hundreds of union leaders across sectors: railways, steel, coal, electricity, and banking. Over 2,000 were jailed, according to the BBC, with the rest cowed into silence. Strikes were banned outright, and the essential legal protections that workers had relied upon were suspended.

The Emergency was a naked war against India’s people - their bodies, their livelihoods and their voices.

By 1976, man-days lost to strikes had plummeted to 2.8 million, from 33.6 million in 1974. The number of strikers fell from 2.7 million to barely half a million. Police raided union offices, seized records, and froze funds (BBC, 2025). The state’s objective was clear: break collective bargaining power and atomise the worker into a solitary, powerless individual.

Among the thousands imprisoned during this period was socialist leader George Fernandes. He was arrested in June 1976 for his alleged involvement in the Baroda Dynamite Case, in which he and others were accused of smuggling explosives and plotting to wage war against the state. His arrest and trial made him one of the most recognisable figures of resistance. The crackdown, however, extended beyond the leaders. George Fernandes’ brother Lawrence and Kannada actress-friend Snehalata Reddy were detained by the police in May 1976, seeking the whereabouts of George. Reddy was interrogated for eight months. She died five days after she was released in January 1977 (Deccan Herald, 2019). The Shah Commission (1978) documented how they were tortured, starved, and beaten, sustaining serious injuries. This case revealed the extent of state violence against leaders, their families, ordinary citizens, and anyone who could be used as leverage to instil fear.

The climate of fear was not limited to the opposition and the unions. It extended into the newsrooms. Newspapers had to submit stories for government approval before printing. A special position of ‘Chief Press Advisor’ was established; every manuscript intended for publication required clearance by this office. Editors were warned, threatened, and some printing presses had their electricity cut to force compliance. Newspapers like Himmat and a few others like the Indian Express and Urdu daily Pratap left editorials blank, on many occasions, as a symbol of protest. More than 250 journalists, including Kuldip Nayar of The Indian Express, were jailed under the MISA. Other editors and reporters were detained for critical coverage of government excesses. Media houses that resisted censorship faced financial penalties, threats, withholding of government advertising, and legal scrutiny. To control the narrative, the government used official agencies to audit or threaten proprietors, tried to place loyalists on boards and delayed payments.

Even the intimate sphere of the family was not spared. Indira’s coercive family-planning policy left lasting scars. Her government implemented aggressive programmes that included forced sterilisation campaigns, disproportionately targeting the poor and marginalised communities. Sanjay Gandhi became a central figure in driving these policies. His campaign brutalised the poor. The police became agents of mutilation, dragging men from slums and villages to be cut against their will. The Emergency was not just a constitutional aberration. It was a naked war against India’s people--their bodies, their livelihoods, their voices.

Ethno-Nationalist Ghosts of Emergency

Five decades later, India again faces a similar crisis, often described as an ‘undeclared emergency’. Just as MISA was weaponised to silence critics, UAPA performs the same role today: to cage dissent without trial. Preventive detention, then and now, stands as one of the defining pillars of an Emergency-like regime. Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) never cease harping on being the victims of 1975, yet they have become its most devoted heirs. Instead of officially declaring an emergency, they are incrementally bending existing laws to concentrate authority.

Case in point: The Bhima Koregaon case. In 2018, a group of Dalits gathered in Bhima Koregaon to commemorate a historic battle against the Brahminical Peshwas. Anti-Dalit violence broke out, allegedly orchestrated by right-wing leaders Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote (The Quint, 2021). Instead of prosecuting them, authorities arrested 16 activists, academics, and lawyers under UAPA, accusing them of a conspiracy to assassinate the Prime Minister (The Guardian, 2024). The ‘BK-16’ included well-known activists such as Sudha Bharadwaj, Anand Teltumbde, and Stan Swamy. Swamy, an 83-year-old Jesuit priest battling Parkinson’s disease, was reportedly denied even basic necessities such as a straw sipper while in custody, where he later died. A subsequent independent forensic probe by the US-based firm Arsenal Consulting revealed that hackers had planted fabricated evidence on the computers of Rona Wilson and Swamy using malware (The Hindu, 2022), in order to falsely implicate them in the alleged Maoist conspiracy.

Father Stan Swamy and others spent decades working with Adivasi communities against displacement and dispossession of their jal, jungle and jameen, in mining districts of Jharkhand (The Wire, 2025). He died in custody awaiting medical bail. It is alleged that the mining cartels circling Maharashtra and Jharkhand had much to gain from silencing Bhima Koregaon’s defenders and branding them as ‘AntiNationals’.

Once again, this account mirrors that of George Fernandes: activists branded as conspirators, charged under draconian laws, and incarcerated as a warning to others. The mechanism has changed, but the authoritarian impulse remains the same. The BK-16 remain trapped in protracted legal processes under UAPA, where bail provisions make release nearly impossible. Both illustrate how governments have used preventive detention to destroy opposition under the guise of national security.

Like the MISA, the UAPA has also been used to target student activists such as Safoora Zargar, Natasha Narwal, Sharjeel Imam, Kanhaiya Kumar, and Umar Khalid (CJP, 2025). Khalid, one of the most visible faces of the protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in 2019, has now spent five years in prison. The case against him rests largely on ‘reverse-engineered’ evidence: unverified witness statements about alleged secret meetings and his inclusion in WhatsApp groups where he never posted any messages. Reportedly, Khalid was not in Delhi when the riots broke out, and the speech prosecutors cite was delivered over a thousand miles away in Maharashtra (Article 14, 2022). Yet, bail has been repeatedly denied, with UAPA provisions invoked to justify his continued detention (SCO, 2025).

What’s worse under the Modi Sarkar is that a ruling-party politician never faces similar consequences for a similar act. This selective impunity is another component of the Emergency playbook, making justice a partisan instrument rather than a constitutional guarantee. A BJP leader indulges in hate speech or communal activity in front of the police and still gets off scot-free. This double standard is evident in the case of the BJP MLA Kapil Mishra (The Caravan, 2020). On February 23, 2020, the BJP leader gave a speech at Maujpur metro

Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) never cease harping on being the victims of 1975, yet they have become its most devoted heirs.

station in Delhi, widely considered incendiary. It is alleged that this speech helped spark the communal unrest in northeast Delhi the next day (The Indian Express, 2020). He threatened the police to remove anti-CAA protestors, saying in a provocative tone: “Three days ultimatum for Delhi Police—clear the roads in Jaffarabad and Chand Bagh. After this, don’t make us understand. We won’t listen to you. Three days.” Eyewitnesses, videos, and even subsequent petitions pointed to his role. Despite the gravity of the accusations against Mishra, no action was taken against him. Instead, Mishra rose within the political hierarchy and now serves as Delhi’s Law Minister. Contrast this with the fate of Umar Khalid.

There is a pattern in how the Indian state, irrespective of the ruling party, responds to dissent: by selectively criminalising agitators and those who disagree, delegitimising the very act of collective resistance. What Indira’s government once did to trade unions, Modi’s has done to farmers’ unions. In 2020, farmers launched a year-long protest against the government’s proposed agricultural reforms. Thousands gathered at the borders of the capital, braving extreme heat, cold, and the Covid-19 pandemic, with many losing their lives. Their demand was the repeal of three controversial laws--the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020; the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020; and the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020. According to farm unions, these laws exposed farmers to exploitation by large corporations and threatened their livelihoods. The protesting farmers were met with barricades, tear gas, internet shutdowns, legal pressure, and police firing at protesters like in Khanauri 2024 (The Hindu, 2024). The crackdown on unions then and farmers now exposes a continuity: whenever citizens organise collectively, the state brands them as enemies.

The Emergency revealed how federalism could be strangled through central overreach, and today the repeated misuse of President’s Rule shows the persistence of this tactic. Another pillar of the Emergency’s authoritarian architecture re-emerges in this practice, with the BJP-RSS alliance repeatedly shaking the federal balance by invoking President’s Rule. Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand in 2016, and most recently in Manipur in 2025.

In Manipur, the ethnic conflict between the valley-based Meitei community and the hill-based Kuki-Zo groups has been underway for over two years, unleashing sexual violence and mass exodus. More than 60,000 people have been forced from their homes and trapped in a prolonged humanitarian crisis. Homes and churches were burnt. Women were paraded naked and violated. As violence spread, government officials and police were reportedly absent, indifferent or complicitan alleged abdication of duty the, compounded by Hindutva politics and the inaction of governments, only deepened the crisis (BBC, 2023). Even till this date, Manipur remains under repeatedly extended President’s Rule (The Hindu, 2025). No resolution has materialised, leaving the state suspended in a limbo.

Primetime Propoganda

Media capture was central to the Emergency then, and it remains so today. The techniques differ: censorship then, co-option and propaganda now. But the goal is the same: to suffocate independent voices and monopolise the national narrative. As in 1975, the government allegedly deploys official agencies to pressure media houses and installs loyalists on boards; the crucial difference, however, is that, unlike then, the media has shown little capacity to resist getting swallowed whole.

The protesters are met with barricades, beatings, tear gas, internet shutdowns, police firing, and arrests.

In a comically distorted echo of the Emergency period, the Indian media has now morphed into amplifiers of the Hindu Rashtra propaganda under Prime Minister Modi. Media analysts note that sensation now often outweighs sense. A study in India Review traces how mainstream outlets helped cocoon the public in nationalist messaging, elevating nationalism while delegitimising dissent.

Opposition leaders are raided until they behave, defect, or fall silent.

Misinformation often spreads most rapidly during times of heightened emotions. For instance, during Operation Sindoor, several news channels telecast sensational but entirely false and unverified reports. These ranged from claims like “Indian Navy Attacks Karachi” to “Pakistan Army chief Asim Munir arrested” (Alt News, 2025).

A CJP (2024) report traces how news channels regularly deploy thumbnails and headlines that scream drama and clickbait, like “Bahraich Hinsa par Yogi ka tagda aylaan, sunte hi kamp uthe ‘Musalman!”, tied to explosive visuals. Such thumbnails echo sectarian politics, especially around communal or violent episodes, intentionally stoke emotions, incite division, and distort reality.

Those journalists who attempt to fight these devious forces are demonised and hunted in reverse. Kappan, a journalist from Kerala, was arrested in October 2020 while he was travelling to report on a case involving the rape and death of a Dalit girl in Uttar Pradesh (BBC, 2023). He was accused of conspiring to incite law and order issues and being linked to a Muslim organisation, though he denied these allegations (The Guardian, 2023). Kappan spent nearly 2.5 years in jail without trial before being granted bail.

Another example of muzzling of dissenting journalism is Mohammed Zubair, co-founder of Alt News. He was arrested in 2022 over a years-old tweet, widely seen as retaliation for his exposure of hate speech (Al Jazeera, 2022). In late 2024, he was again booked for ‘endangering the sovereignty and unity of India’ under the new penal code (The New Indian Express, 2024).

The Carrot, the Stick, the Whip

What was once done overtly during the Emergency now occurs in subtler, more insidious ways. The Emergency brazenly hollowed out institutions to serve the then Prime Minister’s will. Today, central agencies are being weaponised to carry out that hollowing process. The Enforcement Directorate (ED), Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), and National Investigation Agency (NIA) disproportionately target opposition leaders, while the Election Commission of India (ECI) is allegedly doing the ruling party’s bidding. Opposition leaders are raided until they behave, defect, or fall silent.

After Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest on corruption charges, Amnesty International (2024) noted that the BJP-led government’s suppression of dissent and opposition in India had reached a ‘crisis point’. In recent years, a growing number of opposition leaders and independent media outlets, including the BBC, have faced tax raids and lengthy probes by the Enforcement Directorate (ED). Opposition leaders on the campaign trail often describe this pressure as ‘Tax Terrorism’ (France24, 2024; Reuters, 2024).

Meanwhile, defections to the BJP—which appear to be anything but voluntary—have become more frequent, sometimes delivering remarkable outcomes. In February, The Wire (2021) reported that around a dozen opposition politicians who were under corruption investigations, mostly by central enforcement agencies, suddenly saw their cases dropped once they joined the BJP. “The phenomenon is so widespread, political pundits now refer to the BJP as the ‘Washing machine’. An Indian Express report (2024) noted that 25 opposition leaders facing corruption probes saw their cases dropped or put on the back burner after defecting to the BJP, cementing the image of the party.

To add to this, the autonomy of the ECI has been under sustained invasion in recent years. In Anoop Baranwal v. Union of India (2023), the Supreme Court ruled that appointments to the ECI must be made by a committee comprising the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition, and the Chief Justice of India, to insulate the body from executive dominance. Yet, within months, the Union government passed a new law replacing the Chief Justice with a Union Cabinet Minister nominated by the Prime Minister, effectively undermining the Court’s directive and prompting multiple petitions challenging the Act. This erosion of the ECI’s neutrality has drawn strong criticism, with opposition leader Rahul Gandhi even accusing the Commission of colluding with the BJP in “vote chori”, calling it a betrayal of the Constitution and democracy.

The carrot is immunity for the pliant; the stick is endless raids for the disobedient. And the whip is a recently tabled 130th Constitutional Amendment bill.

Compounding these concerns, the now-scrapped Electoral Bonds Scheme revealed how the ruling party misused the enforcement agencies and allowed quid pro quo arrangements, raising concerns about the growing crony capitalism (Time, 2024). The scheme overwhelmingly benefited the BJP, which had secured nearly 90 per cent of all corporate donations through electoral bonds, amounting to close to $2 billion, according to a 2021 report by Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR). “Electoral bonds were supposed to make political contributions transparent. Instead, they became a form of legalised corruption, funnelling huge sums and making the political playing field even more uneven.” (Mudgal, 2024). While donations remained anonymous to the public, the government knew donor identities, enabling it to pressure businesses, monitor opposition fundraising, and extract money through investigative agencies. Many political observers feel that the use of such brazen tactics to incapacitate the Opposition is reminiscent of the Emergency

The carrot is immunity for the pliant; the stick is endless raids for the disobedient. And the whip is a recently tabled 130th Constitutional Amendment bill. According to the bill, a Prime Minister, Chief Minister, or minister can be removed from office if they face a criminal investigation, even before conviction. Elected leaders could automatically lose their posts if they are detained for 30 consecutive days under charges carrying a minimum five-year sentence. It is no coincidence that MPs Rahul Gandhi and Mahua Moitra were hounded and disqualified from Parliament before such a bill emerged. The bill attempts to institutionalise vendetta and appears to be another Machiavellian attempt by the Modi government to concentrate authority and suppress dissenters.

The authoritarian overreach witnessed during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, is once again visible in India under Modi’s leadership. Each sphere of constitutional values–civil liberties, federal balance, media, institutions, safeguards for minorities and other vulnerable sections–seems to have become a cog in the machinery of an undeclared emergency. Over the past decade, religious rhetoric, coupled with majoritarian politics, has not merely complemented electoral campaigning; it has become central to it, shaping political discourse and policy. This approach often normalises discrimination, marginalisation, and, at times, outright violence against minority communities, while portraying dissenting voices as threats to national identity. According to a 2024 report by India Hate Lab, a Washington DC-based group, mob lynchings and hate speeches, particularly those targeting Muslims and Dalits, have surged in recent years while the law enforcers have looked the other way.

The democratic backsliding, akin to that of the Emergency, has been captured by various national and international assessments. The V-Dem Democracy Report (2025) classifies India as an ‘electoral autocracy’, indicating that while elections occur, fundamental rights, institutional checks, and civil liberties are increasingly compromised. Similarly, Freedom House (2024) rates India as ‘partly free’, citing systematic persecution of minorities, the subversion of independent institutions, the weaponisation of laws to suppress dissent, and an unmistakable shift toward Hindu nationalist ideology, a substitute for supremacism.

Just as the Emergency brutalised the most vulnerable, today’s authoritarianism also finds its sharpest edge at the margins of society. BJP’s combination of jingoistic nationalism wedded to crony capitalism has deepened the precarity of women, Adivasis, Dalits, religious minorities, farmers, and workers. For instance, agrarian distress has intensified under policies that prioritise corporate interests over sustainable livelihoods. Women continue to face heightened vulnerability amid unsafe, patriarchal and casteist frameworks, while Adivasis and Dalits struggle against land dispossession and systemic discrimination.

Redressing the notion that history repeats itself, Karl Marx said, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce”, describing how human failings drive absurd repetitions of historical events. The trajectory from Indira’s Emergency to Modi’s rule illustrates this very cycle of repetition. The ghosts of the Emergency still linger in Parliament--not as people, but as patterns of power misuse that now take the form of saffronising textbooks, pushing ethno-nationalist narratives, and passing laws at whim. These ghosts of authoritarianism can only be dispelled when watchful citizens rise to become true custodians of the Constitution.

References

- https://bit.ly/3WGQlkB

- https://bit.ly/4nXmnFd

- https://bit.ly/4n7j6BW

- https://bit.ly/4nXM9cq

- https://bit.ly/4haPjGW

- https://bit.ly/4heNDMR

- https://bit.ly/4n7U9WO

- https://bit.ly/47cgHjg

- https://bit.ly/4hia2J9

- https://bit.ly/42Mcr8R

- https://bit.ly/4q9KH8l

- https://bit.ly/3WIFvKU

- https://bit.ly/47rp9wl

- https://bit.ly/4om9sfJ

- http://bit.ly/3JgPaFx

- https://bit.ly/47rpNdf

- https://bit.ly/48Ac3hC

- https://bit.ly/47cirsO

- https://bit.ly/4opAYJj

- https://bit.ly/4nOy9S9

- https://bit.ly/4hkgijI

- https://bit.ly/4nN2sZo

- https://bit.ly/4namPi7

- https://bit.ly/47rkqL7

- https://bit.ly/47tI7Cw

- https://bit.ly/3Jl3I77

- https://bit.ly/4hbNUzX

NEXT »