Muzzling of the Indian Press

They Crawled When Asked to Bend!

Mohd Aasif*

On June 26, 1975, Aaj, a prominent Hindi newspaper, proclaimed, ‘Sab Narain Jail Mein’ (All the Narains are in jail). It referred to Jayaprakash Narayan and Raj Narain1 . The former led a nation-wide movement against Mrs Gandhi’s government, and the latter filed a petition against her election in the Allahabad High Court, alleging corrupt practices and the misuse of government machinery.

Jayprakash Narayan urged people to lay siege to the PM’s residence, and gave a call to the police, military and bureaucracy to disobey the orders of the “illegal” government and join the movement. Mrs Gandhi treated this call as a potential coup, a threat to democracy in India, and took the action to impose Emergency. She claimed that the Emergency was an attempt to save democracy from “internal disturbances”2 .

The next 21 months saw a wave of repression, mass arrests of opponents, and censorship of the press. The administration targeted journalists and the press, particularly those critical of the government, in general, and of Mrs Gandhi, in particular. For the Indian Press, the Emergency became an existential issue. Mrs Gandhi’s younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, nicknamed ‘super-minister’, was leading the onslaught on the media. He sacked the then Information and Broadcasting Minister, Indra Kumar Gujral, for his ‘failure’ to control the press, replacing him with one of his minions, Vidya Charan Shukla.3

The bulk of the media not only acquiesced but also went an extra mile to please the masters. BJP’s Lal Krishna Advani summed up the predicament aptly, saying, “When you were merely asked to bend, you chose to crawl.”4

Emergency and the Press

Press freedom was one of the first casualties of the new order. It started with cutting the electricity lines of Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg in New Delhi, where a majority of national newspapers had their offices and printing presses. As a result, most of the dailies could not publish and distribute their editions the next day. Two dailies, the Hindustan Times and The Statesman, were ‘spared’ by mistake as their offices were located in Connaught Place. But the copies of their edition were seized by the police.5 They also lost power supply the following day. The power supply was restored only after a censorship machinery was established.6

The attack was not limited to the Indian press; it was extended to Western journalists based in India. The government expelled journalists from highly reputed international papers, including The Times of London, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times. Correspondents of The Guardian and The Economist flew back to the United Kingdom after receiving threats. Mark Tully, the voice of the BBC, was also recalled.7

Journalists were treated as criminals. Henderson (1977) writes about how the government systematically suspended all the safeguards for journalists and the press. First, the government abolished the Press Council, a statutory quasi-judicial autonomous authority responsible for preserving the freedom of the press. Secondly, the legal immunity of journalists for reporting on Parliament was lifted. Thirdly, the government was given the power to prevent the publication of ‘objectionable matter’.

A white paper on the ‘Misuse of Mass Media’, which was brought out after the Janata Party Government came to power after Emergency, revealed that 253 journalists were arrested, 110 detained under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) and 60 under the Defence of India Rules (DIR). The Editor of the Express News Service, Kuldip Nayar, was arrested in Delhi in the early hours of July 25, 1975. Arrests of journalists went on for the rest of the duration of the Emergency. Those arrested included Jagat Narain of Hind Samachar, Jullundur, KR Malkani of Motherland, Chunibhai Vaidya of Bhumiputra, and KR Sundar Rajan of the Times of India, Bombay (Henderson, 1977).

Assistant Editor of the Times of India, Sundar Rajan reported that his office and residence were raided, his phone was tapped, and his mail was seized. He was kept under constant surveillance and interrogated several times, once for a nine-hour long session. On one occasion, he was summoned to the Enforcement Branch of the Cabinet Secretariat on just 20 minutes’ notice and subjected to intense questioning. Hindustan Times editor BG Varghese was sacked by the publication after he wrote critically against Sanjay Gandhi and his pet project, Maruti.8

Press Freedom and Censorship

Crackdown on the press came from all directions, and every department of the Indian State machinery was at the disposal of the Executive to carry out such attacks. Indira Gandhi’s government invoked MISA and the Prevention of Publication of Objectionable Matter Act, in tandem with DIR against journalists. MISA gave the government unchecked power to arrest and detain people without trial. This Act became the iron fist beneath the velvet glove of “national interest”. Journalists, editors, cartoonists, film-makers, or anyone who dared to question the government, were locked away and silenced without due process. This Act did not just detain people; it detained truth. It turned journalism into a crime and made silence the safest headline.

The muzzling of the Press did not stop at MISA. The government used many other methods to control the flow of information. It merged four leading news agencies, the Press Trust of India (PTI), the United News of India (UNI), Samachar Bharati (Newsline) and the Hindustan Samachar (Indian News), into a single agency as Samachar (News). The new agency was then further remanded under strict government control, and the Press Information Bureau (PIB) was used to monitor its newscasts and radio broadcasts.

To make the censorship more stringent, on February 4, 1976, the Rajya Sabha passed the Prevention of Publication of Objectionable Matter Act. Some daring members who were allowed to speak called the bill “controversial”, “draconian”, “vague”, and “authoritarian”. The bill granted the State power to control “prejudicial publications”, extending to the forfeiture of publications and a penalty for material published to “incite” crime.

The Act explained “objectionable matter” as “any words, signs or visible representations which are likely to bring into hatred or contempt, or excite disaffection towards the government established by law in India or in any State thereof and thereby cause or tend to cause public disorder; or incite any person or any class or community of persons to commit “mischief” which is defamatory of the President of India, the Vice President of India, the Prime Minister, or the Speaker of the House of the People, or the Governor of a state; or are grossly indecent, or are scurrilous or obscene or intended for blackmail”.9

State machinery, with the help of this Act, made every possible effort to prevent any kind of criticism in the press against Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her government. While drawing a comparison during a debate, Rajya Sabha member Dr K Mathew Kurian called the bill worse than the 1930 Press Act introduced during Direct British rule and the Press (Objectionable Matter) Act of 1951 introduced postindependence.10

Under the Prohibition of Publication of Objectionable Matter Act (1976), the press was required to deposit a security amount with the government. This money was liable to forfeiture if the press was found to be guilty of publishing “malicious” or “scurrilous” content, thus acting as a pre-emptive penalty mechanism. Navajivan Press, established by MK Gandhi, saw its printing facilities confiscated, while a weekly Himmat, edited by Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson Rajmohan Gandhi, was asked to make a substantial deposit because of certain allegedly objectionable reports.11

The supply and distribution of newsprint, an essential commodity for the publication of newspapers, was used as an instrument of control. Newspapers critical of the government became the target of reduced quotas, limiting their ability to print and circulate copies. This impacted their reach and revenue, making it harder to maintain their operations.12 The Statesman was threatened with a notice alleging “printing excess copies to sell them as waste.” 13

Advertisements serve as the primary revenue stream for newspapers, enabling them to sustain their operations. Both the Central and State governments contribute significantly to this through advertisements paid for with the taxpayer’s money channelled through the Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity (DAVP). However, during the Emergency, DAVP was not only subverted but was made a tool of favouritism, allocating advertisements based on political loyalty. The newspapers were categorised as friendly, neutral, or hostile. Newspapers aligned with the ruling party were rewarded with generous advertisement placements, while critical or dissenting publications were systematically denied support.14

In addition to formal censorship, the government resorted to unconventional tactics to pressure the press. Once again, on September 29, 1976, the power supply to the Delhi press of the Indian Express was abruptly cut off, with a padlock placed on the control panel. Electricity was restored only after intervention by the Delhi High Court. Two days later, the Delhi Municipal Corporation sealed the press without prior notice or explanation. It was later revealed that the action was linked to unpaid municipal taxes. Financial pressure was also used, with Punjab National Bank being employed to block the working capital needed for purchasing newsprint.

The Statesman was among the key targets, with attempts made to gain control through the purchase of its shares (Henderson, 1977). In the case of Himmat, a notice was issued to the magazine’s printers, demanding an explanation as to why their presses should not be confiscated. The government withdrew advertising and pressured private advertisers to do the same. The concessional postal rates applicable to newspapers were not made available to The Statesman. Efforts were also made to bully its shareholders into selling shares.

Press Fights Back

Despite wielding immense power and employing every tool at her disposal, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi could not silence every voice defending freedom of speech during the Emergency. A handful of individuals stood firm—unyielding in their commitment to press freedom. Among them were Ramnath Goenka, Rajmohan Gandhi, Romesh Thapar, George and Leila Fernandes, Chimanbhai Patel, AD Gorwala, Kuldip Nayar, and CR Irani. They chose to shut down their publications, refusing to compromise on their principles.

Ramnath Goenka, drawing from his experience of resisting British rule in 1942 as President of the Nationalist Newspaper Editors’ Conference, chose to follow his conscience and took up his pen against the authoritarian regime of the Emergency. In September 1975, a group of editorial executives declared, “We will fight to the bitter end”.

Mumbai faced similar challenges. Kalpana Sharma, the then editor of Himmat, recalled the publication’s determined stand against the government’s pre-censorship directives, refusing to compromise on journalistic integrity. In an article published in Scroll recently, she recalls: “In July 1976, a CID officer arrived at their office with a notice. It stated that Rajmohan Gandhi, the printer and publisher of Himmat, had to deposit ?20,000 within 15 days with the Commissioner of Police due to “prejudicial reports” in the three April issues. No specific details were provided until the magazine challenged the censorship guidelines in court.”15

Sharma also noted that many journalists went underground to avoid arrest. PK Roy of The Hindu, despite having an arrest warrant issued against him, continued reporting secretly from the Lal Kuan office of Amar Ujala in Lucknow.

In a rare act of defiance, The Statesman challenged a notice from the Company Law Board accusing it of printing excess copies for sale as waste. The paper filed a petition in the Calcutta High Court, which stayed the proceedings and demanded the government justify its action, a bold move in a time when most voices were silenced (Henderson, 1977).

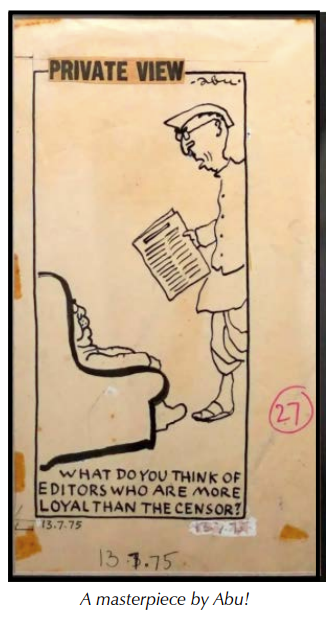

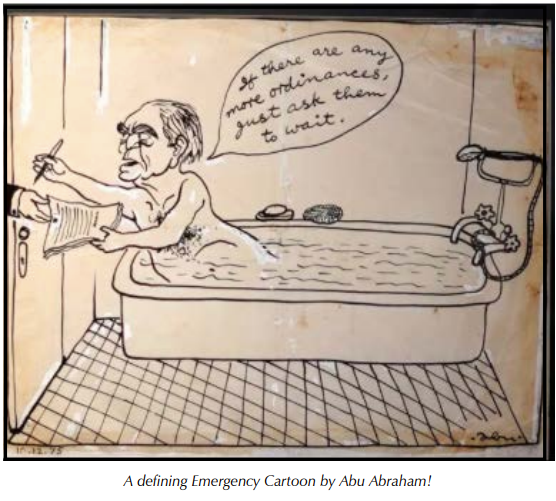

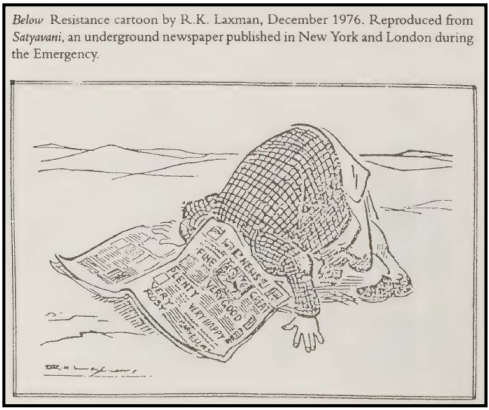

The papers took a creative turn to express their disagreement with the censorship policy. Among them were renowned cartoonists Abu Abraham and RK Laxman, whose works were heavily censored by the appointed bodies.

Bombay edition of The Times of India, on June 28, 1975, carried an obituary notice: “D’Ocracy— D.E.M., beloved husband of T. Ruth, loving father of L.I. Bertie, brother of Faith, Hope and Justicia, expired on 26th June”16 The spoof mourned the death of the democracy and great loss of truth, liberty, faith, hope and justice, the day emergency was declared. It became a popular Emergency joke. “By the time the censors woke up to its true meaning, it was too late.”17 All efforts to locate the author were in vain.

Content and Censorship

All the newspapers in the country required permission before publishing anything. The Chief Press Advisor (CPA), a position that was created to censor the news, would accept or reject matter for publication. The government also warned newspapers against publishing blank editorials, as the Indian Express and some other papers had done, along with mass arrests carried out after the imposition of the Emergency (Kapoor, 2015).

Efforts to contain the content stretched to forbidding the publication of news of those detained without trial. Even the news on the judgment for the release of Kuldip Nayar was not allowed to be printed in the Indian Press. The communication circuit of the Associated Press was cut as it sent the news out to the world. The steps were taken to prevent the comments of the judge saying, ‘No order under the Security Act is beyond challenges’. There were many judges still willing to uphold freedom, and the government retaliated by moving against the judges. Hence, no ‘editorial comments on, or other further references to, the transfer of judges were allowed’ (Henderson, 1977, p. 233). Censors treated every critical thought as an incitement against the state. Apparently, quotations from the luminaries and freedom fighters were not allowed to be published by the papers. It was considered “prejudicial”18. Himmat received a notice from the censors for the same act. “The restoration of free speech, free association and free press is almost the whole of Swaraj”, words of Mahatma Gandhi, offended the censors. The guidelines also instructed papers and magazines not to reproduce rumours or anything “objectionable” that had been printed outside India. But the irony is that only newspapers outside India were reporting “what was actually going on in the country”, recalls Kalpana Sharma.

“Common Man”, a character by cartoonist R.K. Laxman, was also the victim of censorship. Laxman’s cartoons were often not cleared by the Chief Censor’s office. According to his memoirs, “if the censors would understand a cartoon and it tickled his wit, he immediately banged the rubber stamp ‘Rejected’ on it on the basis that something that made people laugh might be an anti-government reaction. But if the cartoon showed no scope for laughter at all, it got the reject stamp even so because it might harbour pernicious intentions.”19

Films Under Censor

The censorship regime of the Emergency period extended beyond the press and to the film industry, which came under the direct influence of Sanjay Gandhi and his close associates.

Two films became emblematic of censorship and suppression: Kissa Kursi Ka, directed by Amrit Nahata, a political satire allegedly targeting the ruling establishment, was banned and was only released after the Janata government came to power; and, Aandhi, written by Kamaleshwar and directed by Gulzar, was withdrawn from circulation on the grounds of violating the Model Code of Conduct, with the government claiming it could harm the Congress party’s image. The movie tells a tale of a politically driven woman, Aarti Devi. Her rise in public life comes at the cost of her personal relationships, subtly echoing aspects of Indira Gandhi’s personal life.

Press Paid the Price

Authors like Henderson, Coomi Kapoor, and Kuldip Nayar give a detailed account of how resistance by the Indian Press during the Emergency came at a heavy price. Several titles closed down due to the obstruction of the revenues in the form of advertisement or government patronage. Many were forced to shut down due to ‘irregularities’ or ‘non-payment of electricity bills.’ As one of the tactics, Censors delayed the approval of newspaper content, leading to a delay in publication and, eventually, a loss in circulation, readership, and advertising revenue.

The crackdown began with the Eastern Economist, which struggled for six months before its editor, V Balasubramanian, announced its closure on January 16, 1976. Soon after, on July 13, 1976, The Opinion, a monthly newsletter edited by 75-year-old AD Gorwala and circulated among intellectuals in Bombay for 16 years, was also forced to shut down.

Seminar, a respected monthly, chose to suspend publication after its publisher, Romesh Thapar, was ordered to submit the August 1977 issue on ‘Fear and Freedom’ for pre-censorship, a demand the magazine found unacceptable. Around the same time, Pratipaksha, published by George and Leila Fernandes, was also discontinued.

In Poona (present-day Pune), the publication Sadhana changed its name to Kartavya, but its Managing Director was imprisoned. In Gujarat, the daily Sandesh, edited by Chimanbhai Patel, endured significant financial losses rather than compromise its editorial independence. Many publications were forced to change printers frequently to avoid government interference. After months of resistance, the 14-year-old weekly Mainstream finally ceased publication, choosing closure over submission to censorship.

Propaganda Machinery

Utilisation of state machinery was not limited to curbing of the press and anti-establishment reporting. It was further used to spread pro-government propaganda. In a further breach of neutrality, DAVP funds were used to promote Congress Party souvenirs, an act that blatantly misused public resources. Opposition parties received no such backing. What was intended as a framework for fair distribution of government support turned, in practice, into a mechanism of exclusion and control.

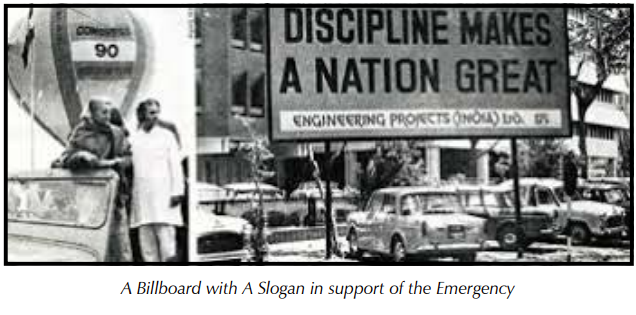

In later years, the Shah Commission, which was set up to enquire into the excesses committed during the Emergency, noted, “In practice, censorship was utilised for suppressing news unfavourable to the government, to play up news favourable to the government and to suppress news unfavourable to the supporters of the Congress party”20. Journalists were forced to give laudatory coverage to Sanjay Gandhi and his family planning programme which forcibly sterilised men, and dismiss reports related to the opposition in a couple of paragraphs.

CR Irani, the then Managing Director of The Statesman, accused government officials of attempting to ‘dictate’ to newspapers. Newspapers, he said, had even been charged with failure to publish Mrs Gandhi’s photograph often enough on their front pages. The Statesman’s Resident Editor in Delhi, S Nihal Singh, was asked by the Information and Broadcasting Ministry to publish certain photographs in a particular manner and to give greater prominence to Congress party pronouncements (Henderson, 1977).

The Film Division, a government body, through the production of the films, devoted itself towards the projection of the image of the Prime Minister and painting a good image of the Emergency. “Our Prime Minister” tries to paint Mrs Gandhi’s image as a benevolent leader. The Film Division movies reiterated slogans like, “Discipline makes a nation great” in their campaigns.

Conclusion

The government and its institutions, since the beginning of Emergency, tried to justify it. Even the suspension of the right to freedom of expression was justified in the name of saving democracy.

Emergency was not only about the suspension of rights. It was the reflection of the fear of losing power. Mrs Gandhi, in reality, waged a war against democracy. In the name of saving democracy, she gagged the freedom of expression, an essential element of democracy. Since it was also a war of narratives, press censorship acted as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it slashed material critical of the government and its offices, and on the other it pushed government propaganda.

The shadow of the Emergency on the press can still be seen through internet shutdowns, shadow bans on websites and Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP) imposed on the individuals and vulnerable media outlets.

References

- Ninan, S. (2007). Headlines from the heartland : reinventing the Hindi public sphere. SAGE Publications.

- Premila Menon Mussells, “Democracy and Emergency Rule in India: Political Change Under Mrs Gandhi,” The University of Oklahoma, 1980.

- Kapoor, Coomi. (2015). The emergency: a personal history. Penguin, Viking.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe., & Anil, Patrinav. (2021). India’s first dictatorship : the emergency, 1975-77. Hurst & Company.

- supra note 3

- supra note 2

- https://bit.ly/4hjVsRw

- Verghese, B. (2018). The last word. In V. Anand, K. Jayanthi (Eds.) The last word (pp. 2-6). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9789353280277.n1

- https://bit.ly/3Jf0ORd

- https://bit.ly/3WHIuTU

- https://bit.ly/3WHIuTU

- https://bit.ly/3WHIuTU

- supra note 7

- https://bit.ly/47a25RI

- http://bit.ly/4heajgc

- supra note 3

- supra note 15

- https://bit.ly/43gQzT9

- https://bit.ly/4nM4lFI

NEXT »