State of Judiciary During Emergency

From Assertiveness to Acquiescence

Swapna Jha*

The proclamation of Emergency on June 25, 1975, one of the darkest chapters in the history of Indian democracy, was declared under Article 352 of the Constitution on the ground of “internal disturbance”. It lasted until March 1977 and witnessed the suspension of civil liberties, severe restrictions on the press, and the large-scale detention of political opponents without trial.

In this period of extraordinary executive dominance, the role of the Indian judiciary became pivotal and posed a serious test to its independence. The courts, expected to safeguard fundamental rights, faced the gravest test of their institutional integrity. This article explores the judiciary’s role during Emergency, with specific reference to leading case laws and their long-term implications.

In the years preceding Emergency, the judiciary asserted itself as a guardian of the Constitution, played a pivotal role in shaping the contours of constitutional law and in asserting itself as a check on the executive. The political climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s was marked by growing tensions between the legislature, which often sought to expand its power, and the judiciary, which sought to preserve constitutional limits. This confrontation became especially evident in the sphere of constitutional amendments and fundamental rights.

A defining moment came with the landmark judgment in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973). In this case, the Supreme Court held that while Parliament had wide powers to amend the Constitution, it could not alter its “basic structure”. This doctrine implied that certain fundamental features of the Constitution, such as the supremacy of the Constitution, judicial review, democracy, secularism, and the protection of fundamental rights, could not be abrogated even by constitutional amendments.

The judgment was hailed as a triumph of judicial independence, but it also sowed the seeds of a lasting confrontation between the executive and judiciary. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi saw the decision as a serious limitation on parliamentary sovereignty. The confrontation deepened in 1973 when the government superseded three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court--Justices Shelat, Grover, and Hegde--after they ruled against the government in Kesavananda Bharati case. Instead, Justice AN Ray, who had sided with the government, was appointed as the Chief Justice of India. This act of supersession was widely condemned by the legal community as an assault on judicial independence, but it also revealed the government’s willingness to manipulate the judiciary to serve its political interests.

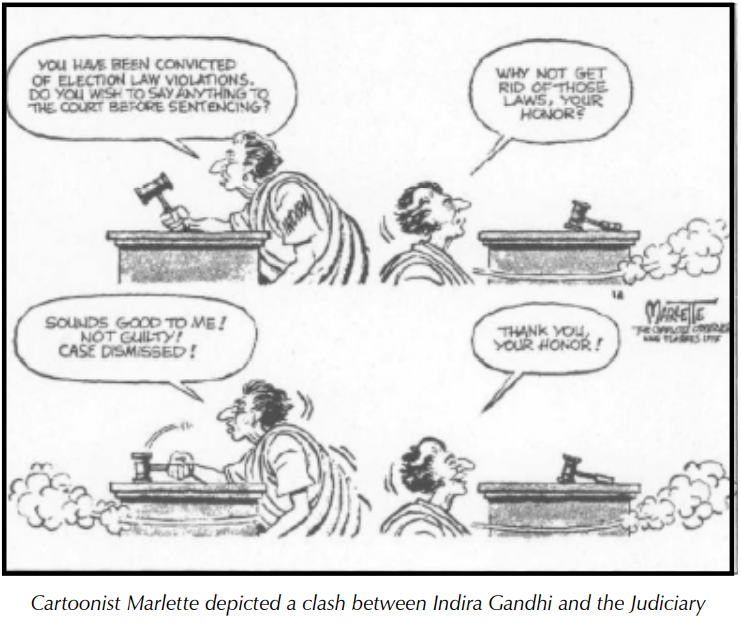

The judiciary again asserted its authority in Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975)1 . In this case, the Allahabad High Court invalidated Indira Gandhi’s election on grounds of electoral malpractice. Though the Supreme Court later granted her a conditional stay, the decision struck at the very heart of her political legitimacy. This ruling is often regarded as the immediate trigger for the proclamation of the Emergency, as it threatened to unseat the PM and destabilise her government.

These judicial interventions made clear that the courts were not willing to blindly endorse the executive’s agenda. However, the very assertiveness that defined the judiciary before 1975 set the stage for its subsequent curtailment. The government increasingly viewed the judiciary as an obstacle to its authority, and once the Emergency was declared, the executive moved decisively to neutralise its independence.

The proclamation of the Emergency brought sweeping changes to constitutional governance. Articles 19, 21, and 22 were effectively suspended and thousands of citizens were detained without trial. High Courts initially displayed courage, granting relief to detenus under habeas corpus petitions. However, this fragile independence collapsed in the infamous case of Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla2 . The majority opinion, led by Chief Justice AN Ray, held that during the Emergency, even the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 stood suspended, and no writ of habeas corpus was maintainable.

The judiciary in a constitutional democracy is regarded as the ultimate guardian of the rule of law and the protector of fundamental rights. Its primary role is to ensure that the executive and legislative branches act within the framework of the Constitution, and that citizens are shielded from arbitrary state action. However, during the Emergency, this role came into question and exposed its vulnerability to political pressures.

From the very beginning of Emergency, the executive sought to bring the judiciary firmly under its control. Judges perceived as independent or critical of government policies were transferred to distant High Courts under the guise of “administrative necessity”. These transfers were seen by many as punitive measures intended to intimidate the judiciary. At the same time, judicial appointments increasingly reflected considerations of loyalty rather than merit. The supersession of judges in 1973 had already set a precedent, and during the Emergency, the executive used such tactics to ensure that the higher judiciary would not obstruct its agenda.

ADM Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla (Habeas Corpus Case, 1976)

The defining moment of the judiciary’s conduct during the Emergency came with the case of Additional District Magistrate, Jabalpur v. Shivkant Shukla, commonly known as the Habeas Corpus Case. Thousands of political opponents, activists, and critics had been detained without trial under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA). Many of them approached high courts across the country, filing habeas corpus petitions to challenge their detention. Several high courts ruled in their favour, holding that even during an emergency, the right to seek judicial remedy against unlawful detention could not be extinguished.

The very assertiveness that defined the judiciary before 1975 set the stage for its subsequent curtailment. The government increasingly viewed the judiciary as an obstacle to its authority, and once the Emergency was declared, the executive moved decisively to neutralise its independence.

The government immediately appealed these rulings in the Supreme Court. The central question before the Court was stark: when the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 had been suspended during the Emergency, could a citizen still approach the judiciary for relief against arbitrary detention?

In a deeply controversial judgment, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court ruled by a 4–1 majority that no such remedy existed. The majority, Chief Justice AN Ray, Justice MH Beg, Justice YV Chandrachud, and Justice PN Bhagwati, held that during the Emergency, when fundamental rights were suspended, citizens could not challenge their detention in a court of law. Effectively, this meant that the executive had absolute and unreviewable power over the life and liberty of citizens during the state of Emergency.

The judiciary’s conduct during the Emergency revealed the vulnerability of judicial independence in the face of political dominance and this failure was not just institutional but also moral. It demonstrated that constitutional rights could be rendered meaningless if courts refused to enforce them.

Justice HR Khanna was the lone dissenter. In his historic dissent, he argued that the right to life and liberty was not a gift of the Constitution but a natural and inalienable right inherent in every human being. Even in the absence of Article 21, he contended, no authority had the power to deprive a person of life or liberty without lawful justification. His dissent came at great personal cost: shortly after the judgment, Justice Khanna was superseded in the appointment of Chief Justice of India, leading to his resignation. Nevertheless, his dissent has been celebrated as a moral high point in Indian judicial history.

This case epitomised the judiciary’s failure to uphold constitutionalism and its willingness to endorse the suspension of fundamental rights in the face of executive pressure. The case remains a cautionary tale about how fragile the rule of law can become when courts abdicate their role as protectors of liberty.

Systematic Erosion of Judicial Review

The Emergency witnessed a systematic erosion of judicial review. Preventive detention laws like MISA and the Defence of India Rules (DIR) were given sweeping scope, and the judiciary refrained from intervening. Thousands of detentions were rubber-stamped by courts, with judges often invoking technicalities to dismiss petitions rather than question the legality of state action.

Judges who attempted to stand up to the executive faced severe consequences resulting in members of the judiciary choosing silence or acquiescence over confrontation. Judicial activism, which had flourished in the early 1970s, all but disappeared. Instead, the judiciary became an instrument for legitimising the government’s authoritarian policies.

The Shah Commission of Inquiry3 , appointed after the Emergency, later observed that the judiciary had failed in its duty to act as a bulwark against the excesses of the executive. It noted that while individual judges might have acted under pressure or out of fear, the net effect was the erosion of public confidence in the judiciary’s independence.

The judiciary’s conduct during the Emergency revealed the vulnerability of judicial independence in the face of political dominance and this failure was not just institutional but also moral. It demonstrated that constitutional rights could be rendered meaningless if courts refused to enforce them, and the rule of law could collapse when the judiciary abandoned its role as the guardian of the Constitution.

For many citizens detained without trial, the courts provided no recourse. For journalists, activists, and opposition leaders, the judiciary’s silence was tantamount to complicity in the suppression of democracy. The promise of the Constitution, that every individual’s liberty would be protected against arbitrary state action, was rendered hollow during this period.

To regain its legitimacy and restore public trust, the judiciary embarked on a path of self-correction and reassertion of its independence after the Emergency. This period was marked by judicial introspection.

The Moment of Reckoning

When the Emergency was lifted in March 1977 and fresh elections were held, the Janata Party came to power with a strong mandate. For the judiciary, this was a moment of reckoning. Its conduct during the Emergency, particularly in the ADM Jabalpur case, had drawn widespread criticism from legal scholars, the media, and the public. To regain its legitimacy and restore public trust, the judiciary embarked on a path of self-correction and reassertion of its independence. This period was marked by judicial introspection. The courts now sought to strengthen the scope of fundamental rights and reinforce the principle of judicial review.

The 44th Constitutional Amendment (1978) curtailed the power of the executive to proclaim an Emergency by replacing “internal disturbance” with “armed rebellion” as the ground for a national Emergency. It also ensured that certain fundamental rights, such as the right to life and liberty under Article 21, could not be suspended even during an emergency. These changes reflected a clear recognition of the judiciary’s failings during 1975–77 and aimed to provide stronger safeguards for the future.

The judiciary itself began to expand constitutional protections through progressive judgments. The most notable among these was Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978)4 . The case arose when the government impounded the passport of journalist Maneka Gandhi without furnishing reasons. The Supreme Court seized the opportunity to revisit the meaning of Article 21. In a landmark ruling, it held that the right to life and personal liberty could not be interpreted narrowly; instead, it encompassed a wide range of rights essential to human dignity. Importantly, the Court declared that no procedure that was “arbitrary, unfair or unreasonable” could be considered valid under Article 21. By linking Article 21 with Articles 14 (equality before law) and 19 (freedom of speech and expression), the Court created a powerful triad of rights that expanded the scope of judicial protection.

Subsequent cases reinforced this trend. In Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980)5 , the Court struck down amendments that sought to give unchecked primacy to Directive Principles of State Policy over Fundamental Rights. The judgment reaffirmed the basic structure doctrine established in Kesavananda Bharati and emphasised that harmony between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles was essential to the Constitution’s identity.

The judiciary sought to fortify the independence of the institution itself. Over time, this led to the Collegium System (evolving through the Second Judges Case, 1993, and subsequent rulings), which placed greater control of judicial appointments in the hands of the judiciary rather than the executive. While the collegium system has its critics, it reflected the judiciary’s resolve to guard against executive interference, a direct lesson from Emergency years.

Notably, the ADM Jabalpur decision was later discredited by the judiciary itself. In Justice KS Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017), the Supreme Court explicitly acknowledged that ADM Jabalpur was wrongly decided and overruled it. This belated correction underscored the judiciary’s recognition of its past failures and its desire to reaffirm the primacy of constitutional liberties.

Conclusion

Scholars and commissions have been critical of the judiciary’s role during the Emergency. The Shah Commission Report condemned the judiciary’s abdication of responsibility in ADM Jabalpur. AG Noorani and HM Seervai described the period as a constitutional breakdown facilitated by judicial surrender.6 Critics argue that the Court’s failure was not just institutional but also moral, as it undermined public trust in the rule of law7 .

The judiciary’s role during the Emergency of 1975–77 reflects both failure and redemption. In ADM Jabalpur, the Supreme Court failed to protect the most basic rights of citizens, exposing the fragility of constitutional guarantees in times of crisis. Yet, the post-Emergency era demonstrated the judiciary’s resilience, where it sought to restore public confidence and assert its independence. The legacy of this period continues to shape India’s constitutional order, underscoring the judiciary’s vital role in safeguarding democracy.

References

- Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain*, AIR 1975 SC 2299

- AIR 1976 SC 1207

- Shah Commission of Inquiry Report (1978)

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India*, AIR 1978 SC 597

- Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India*, AIR 1980 SC 1789

- H.M. Seervai, Constitutional Law of India, Vol. II

- Granville Austin, Working a Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience

NEXT »