Is Legal Aid Working for the Poor?

IS FREE LEGAL AID WORKING?

For the Poor or The Poor Legal Aid?

Legal aid – free legal services for those unable to afford representation – remains a cornerstone of meaningful access to justice. In recent years, there has been a progress: campaign-style outreach has raised awareness and overall system reach has expanded. Between April 2023 and March 2024, the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) reported providing legal aid to 15.5 lakh people, up from 12 lakh in 2019. State and central budgets have expanded, Lok Adalat disposals remain steady, and targeted interventions, especially mediation, have widened access. Jail-based legal clinics have increased, the Legal Aid Defence Counsel (LADC) system has rolled out nationally, and gender diversity among legal aid personnel has improved.

Yet, several structural concerns persist. Funds are not always optimally used, human resources remain unevenly deployed, and quality control continues to be challenging. While new modes of access, such as a national toll-free helpline and single-window online applications represent important shifts, the decline of village-level legal aid clinics and the shrinking cadre of paralegal volunteers raises serious concerns about accessibility for the most marginalised communities.

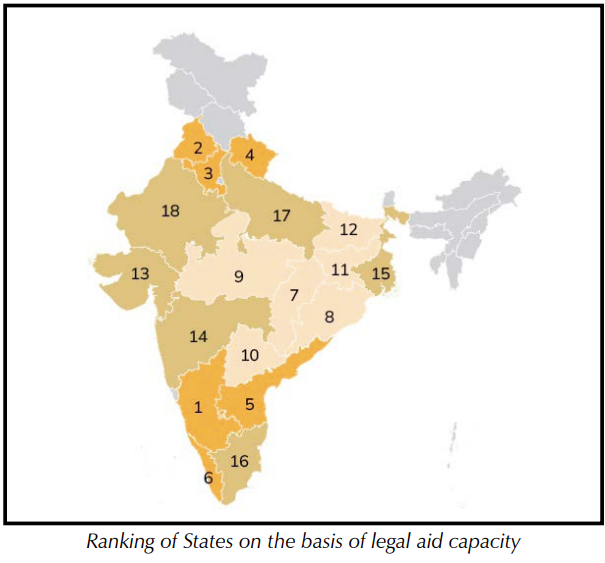

Human Resources

India’s legal aid system is vast but unevenly staffed. As of December 2024, there are 709 District Legal Services Authorities (DLSAs) and 2,376 Taluka Committees. Although the 25 ranked states comprise 586 judicial districts, NALSA records 615 DLSAs due to administrative variations. For example, Arunachal Pradesh has 25 DLSAs for 7 districts, and Sikkim has 6 for 4 districts. Yet only 582 sanctioned posts exist for full-time secretaries, leaving many authorities without mandated leadership. Uttar Pradesh (71 posts for 74 DLSAs), Kerala (13 for 14), Sikkim (2 for 6), Arunachal Pradesh (5 for 25), and Mizoram (none for 8) highlight this mismatch.

Lawyers

Empanelled lawyers have declined sharply. In September 2024, 41,553 lawyers were on panels – a 17 per cent drop since 2022 and 35 per cent since 2019, likely reflecting the shift toward the public-defenderstyle LADC model. Distribution remains uneven: Tamil Nadu (32 districts) had 4,247 panel lawyers, and Maharashtra (34 districts) had 3,401. In contrast, Madhya Pradesh (50 districts) had 1,593, and Uttar Pradesh (74 districts) only 1,871. Although 6,715 serve as remand lawyers, their geographic deployment is undocumented.

Paralegal Volunteers (PLVs)

The steepest human resource decline concerns PLVs. Regulations require at least 50 PLVs per district, amounting to 35,450 for 709 DLSAs. In 2019, there were 69,290 PLVs; by September 2024, only 43,050 remained. Seven states recorded declines exceeding 60 per cent, including Himachal Pradesh (97 per cent fall), Goa (81 per cent), and Tamil Nadu (73 per cent). The PLV-to-population ratio has halved from six per lakh population to three.

Only 14,691 PLVs are “deployed” in police stations, prisons, front offices, and child protection institutions, with Bihar, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra accounting for 43 per cent of them. Karnataka, despite reporting 5,000 PLVs, recorded only 11 deployed. Attrition is driven by low recognition, inadequate training, resource constraints, heavy caseloads, and the absence of remuneration or career pathways. Many PLVs, particularly in remote areas, work in isolation with limited institutional support.

Diversity

The legal aid system displays much greater gender diversity than the police, prisons, or judiciary. As of March 2024, women constituted 31 per cent of DLSA member-secretaries, with seven states recording 60 per cent. Only Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Rajasthan had no women in the post. Among PLVs, women’s representation rose from 36 in 2019 to 42 per cent in 2024.

Transgender representation, however, has sharply declined. From 587 transgender PLVs in 2022, only 139 remained by 2024 – a reduction of more than 76 per cent. Maharashtra dropped from 183 to just seven. Karnataka (33) and Uttar Pradesh (31) had the highest numbers, while 17 states and UTs reported none.

Infrastructure

Village Legal Clinics

Village legal services clinics – intended as grassroots legal care centres – are facing near-systemic collapse. Numbers fell from 14,161 clinics in 2017-18 to 3,659 in March 2024. Each clinic now serves an average of 163 villages, compared to 42 earlier. Several states saw dramatic reductions: Chhattisgarh declined from 281 clinics to one, Jharkhand from 375 to 27, and Telangana from 260 to 23. Coverage is especially poor in larger states: Maharashtra has one clinic per 214 villages; Rajasthan, one per 333; Telangana, one per 440. Karnataka and Jharkhand fare even worse at 856 and 1,092 villages per clinic, respectively. Chhattisgarh’s one clinic for nearly 20,000 villages effectively eliminates grassroots access.

Prison Legal Aid Clinics: In contrast, legal aid within prisons has improved. NALSA’s 2022 regulations require clinics in every prison, staffed by jail-visiting lawyers and PLVs. By March 2024, 1,215 clinics existed across 1,330 prisons, although 20 states/UTs still lacked full coverage.

Workload

Lok Adalats

Between April 2023 and March 2024, 9,865 Lok Adalats handled 22.5 lakh cases. Only 20 per cent were pre-litigation matters; the rest were pending court cases. Five states – Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Telangana – conducted nearly 80 per cent of all Adalats, while 12 states/UTs held none.

Clearance rates were highly uneven. Nationally, 54 per cent of cases were settled. Telangana and Delhi resolved more than 90 per cent. Uttar Pradesh cleared 40 per cent of its 10 lakh cases, Kerala 24 per cent of just over a lakh, and Tamil Nadu 18 per cent of 1.9 lakh. Gujarat cleared only 2 per cent of 11,000 cases, Rajasthan 3 per cent of 40,000, and Maharashtra 9 per cent of 6,000.

Both NALSA and state governments fund legal aid, but proportions have shifted: central contributions have decreased as state contributions increased

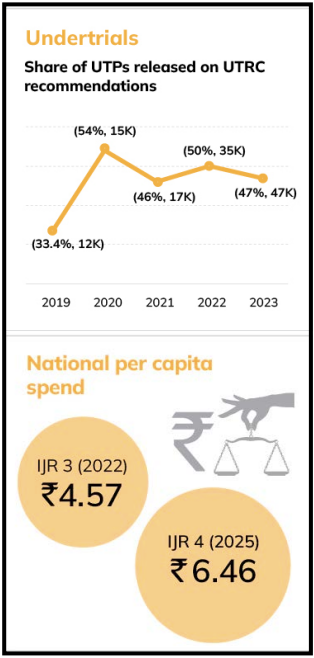

Budgets and Spending

Both NALSA and state governments fund legal aid, but proportions have shifted: central contributions have decreased as state contributions increased. Five years ago, several states contributed little to nothing; by 2022–23, all states participated in funding. Still, the system remains severely underfunded. National per-capita spending averages only Rs 6. Sikkim spends Rs 109 per capita, followed by Tripura (Rs 59), Mizoram (Rs 36), and Goa (Rs 32). Sixteen states, including most large ones, spend under Rs 10 per capita.

Victim Compensation

Although Delhi, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh together awarded 46 per cent of total compensation nationwide, states with high crime rates – such as Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra – awarded comparatively little. Uttar Pradesh, despite over 4 lakh registered applications, awarded Rs 1.85 crore. Compensation determined by LSIs is often delayed due to inconsistent procedures, funding shortages, and variation in compensation amounts across states.

NEXT »