Why Capacity Fails Policing

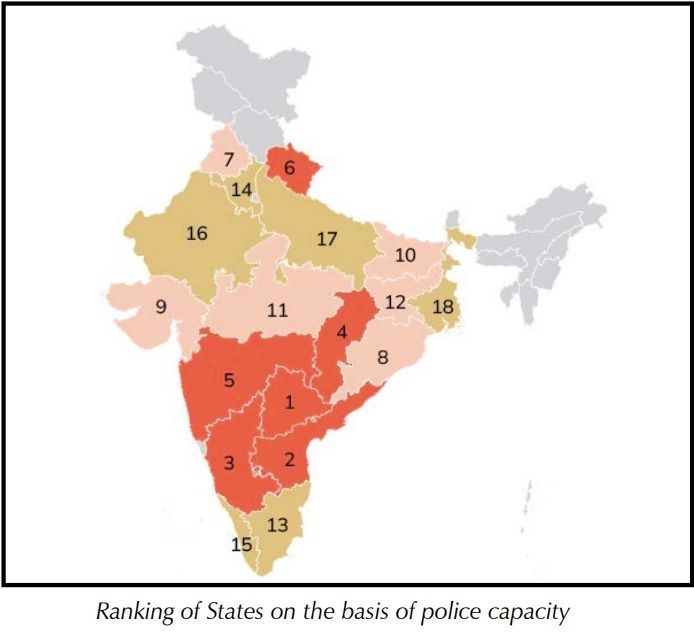

A State-wise Ranking

India’s police force remains deeply constrained by vacancies and uneven distribution. As of January 2023, the sanctioned strength of civil police across the country stood at 21 lakh, with 16.6 lakh constables and the rest being officers – ranging from Assistant Sub-Inspectors to Director General of Police. Yet the actual strength was just over 16 lakh, leaving a persistent shortfall. Nationally, the vacancy rate has hovered between 21–23 per cent for years, with officer posts facing a sharper deficit of 28 per cent compared to 21 per cent among constables.

The picture varies widely across states. At the constabulary level, West Bengal reported a staggering 41 per cent shortfall, while Uttarakhand had almost none, at just 0.6 per cent. Only nine states managed to keep vacancies below 10 per cent; elsewhere, gaps ranged from 13 to 39 per cent.

Population per civil police: As of January 2023, one police person (civil and district armed combined) served 831 people nationwide, unchanged from 2022. In seven states and UTs, each officer served more than 1,000 people. Punjab fared best among large states, with one police person for every 504 people, while Bihar was worst, with one for every 1,522 people.

Infrastructure

Police Stations and CCTVs: Infrastructure gaps compound human resource shortages. In 2020, the Supreme Court’s Paramvir Singh Saini ruling mandated CCTV installation in all police stations, with strict specifications: night-vision capability, 12–18 months of storage, and coverage of 14 locations including entry points, corridors, lockups, and inspector rooms. By January 2023, 83 per cent of police stations reported at least one CCTV, up 10 percentage points from the previous year. Fourteen states achieved near-universal coverage (90–99 per cent), but others lagged badly. Manipur had just 4 per cent coverage, while Puducherry and Lakshadweep reported none.

Women’s Help Desks: Women’s help desks, intended to provide accessible support for survivors of crime, require at least one woman officer, ideally above head constable rank, supported by external networks of lawyers, psychologists, and NGOs. Their effectiveness is undermined by the low overall representation of women in the police. Still, progress has been steady: from 59 per cent of police stations in 2021 to 78 per cent in 2023. Urban stations reported higher coverage (91 per cent) than rural ones (87 per cent).

The biggest gains came from Meghalaya, Bihar, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh. Yet five states and UTs— including Jharkhand, Lakshadweep, and Nagaland—still had fewer than 60 per cent of stations equipped.

Population per police station: Police stations are the public’s first point of contact with the justice system. Between 2017 and 2023, both urban and rural stations saw rising workloads. A rural station that served 83,000 people in 2017 now serves nearly 100,000. In cities, the average jumped from 74,000 to over 93,000. The disparities are stark: an urban station in Arunachal serves just 8,500 people, while one in Gujarat covers 2.8 lakh. In Kerala and Maharashtra, averages exceed 2 lakh per station.

Area per police station: Geographic coverage has also worsened. Rural police stations declined by 735 between 2017 and 2023, forcing remaining ones to cover far larger areas. The National Police Commission recommends 150 sq. km per rural station, but Assam averages 821 sq. km—nearly nine times the benchmark. Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Rajasthan also exceed 600 sq. km. Urban stations, by contrast, cover an average of just 19.6 sq. km.

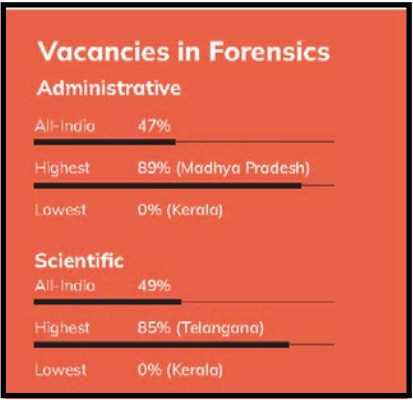

Forensics:

Globally, forensic units are required to function independently of police establishments. However, in India, state forensic units are funded as part of police budgets and often supervised by senior police officers. As of 2023, India had 711 forensic facilities, including state and regional labs and district mobile units. Together, they had a sanctioned staff strength of 7,997, but half the posts lay vacant. According to a 2023 report, 3.6 lakh cases were pending in various forensic laboratories across 26 states.

Moreover, scientific staff only comprise one-third of the sanctioned staff, with first responders to a crime scene, responsible for its processing, have the least number of scientific staff sanctioned to them. There are just 341 scientific staff across 582 units with Telangana (91%), Bihar (85%), and Uttarakhand (80%) registering the highest vacancies.

Budgets

Spend on police per person: Budgetary allocations remain skewed toward salaries and pensions. In 2015–16, the average spend per police person was Rs. 823; by 2022–23, it had risen to Rs. 1,275. Yet over 90 per cent of police budgets go to recurring expenses, leaving little for modernisation, equipment, or capacity-building.

Diversity

Gender: The national benchmark for women’s representation in the police is 33 per cent. While many states align their quotas with 33 per cent, many set their own quotas, which range from 10 per cent in Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya to 35 per cent in Bihar. As of December 2023, Goa, Kerala, Ladakh, Manipur, and Mizoram had no reservations at all. Bihar leads among large states with 24 per cent women, ahead of Andhra Pradesh at 22 per cent. Yet 17 states and UTs report women’s representation below 10 per cent.

Caste: Caste-based reservations show mixed outcomes. Karnataka stands out as the only state consistently meeting its targets across SC, ST, and OBC categories at both officer and constabulary levels. Gujarat, Manipur, and Himachal Pradesh fulfilled SC quotas across ranks. Bihar, Himachal, and Karnataka performed well on ST representation. For OBCs, nine states and UTs met their quotas. Tamil Nadu, Sikkim, and Kerala have over 40 per cent reservation for OBCs, though Kerala and Sikkim still fell short of their targets.

NEXT »